America is Better Than Its Politics

The World Happiness Report shows America in the top tier of the world’s happiest countries, so why does everyone seem so on edge?

If you had to guess whether Americans in the aggregate expressed more or less life satisfaction at the end of 2020 compared to the period of 2017-2019 prior to the pandemic, what would you say?

Okay, you’re a smart crew. I got it wrong.

As measured by a long-standing Gallup question about life satisfaction reported in this year’s UN World Happiness Report, Americans were actually happier at the end of 2020 than they were just a few years prior.

How can this be?

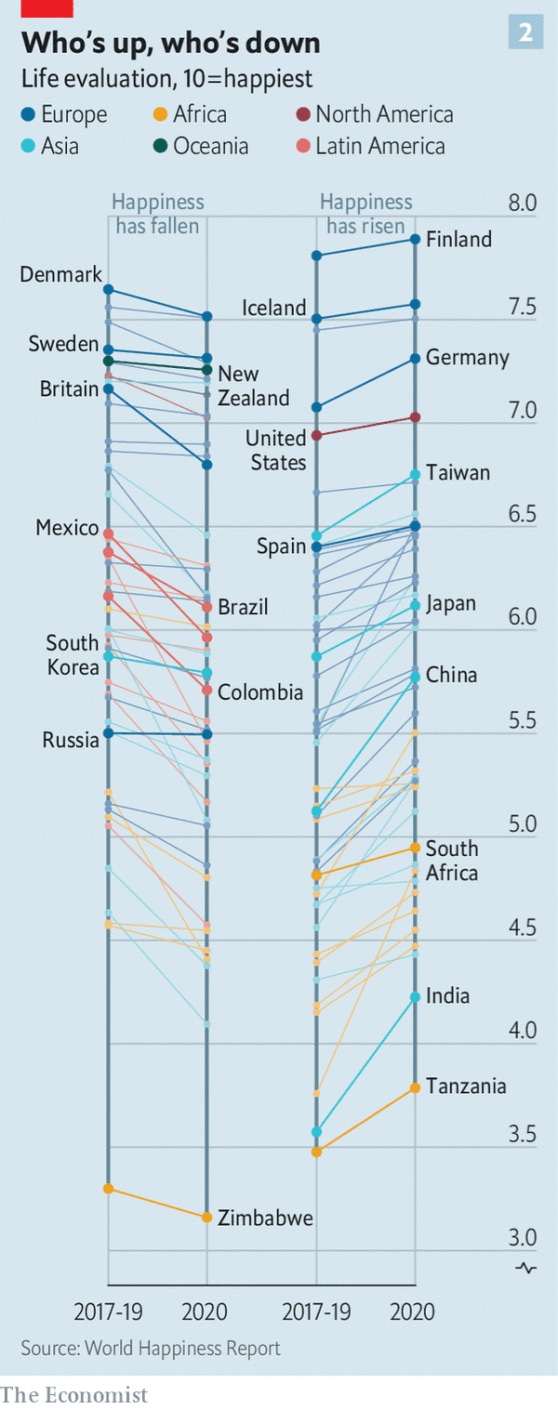

The Gallup World Poll question used in the report has been around since the 1960’s and asks people to evaluate their current life as a whole using the image of a ladder, with the best life possible at the top rung ‘10’ and the worst life possible down on the floor at ‘0’. Weighted national averages are created to compare countries and provide rankings as seen in the table below, showing the top tier of countries with average national happiness ratings between ‘7’ and ‘8’ on the ladder, and the bottom tier showing people on average on rungs ‘3’ to ‘4’.

Northern European countries like Finland, Iceland, and Denmark emerge as the happiest countries, along with perennially cheery places like Switzerland, Austria, and New Zealand. In contrast, life seems particularly less satisfying to people in many countries in the Middle East and Africa, like Jordan or Zimbabwe. China falls in the middle of countries with about a ‘5’ average, and India in the bottom tier at ‘4’.

The United States comes in at number 14 in the new rankings, with an average life satisfaction above ‘7’ on the ladder. Notably, this marks an improvement in Americans’ ratings of their life satisfaction from prior to the pandemic.

The report authors look at a number of factors related to life satisfaction and find the usual suspects of high GDP and strong social welfare provisions emerging as major explanatory variables for national happiness, particularly in those Nordic outliers but also in countries like Germany, Canada, and the U.K. They also examine the importance of national responses to the coronavirus pandemic, and interestingly the role of social trust in shaping national happiness. As The Economist reports (italics added):

Strikingly, the countries that were at the top of the happiness chart before the pandemic remain there. The three highest-ranking countries in 2020—Finland, Iceland and Denmark—were among the top four in 2017-19. All three have dealt well with Covid-19, and have excess-death rates below 21 per 100,000. Iceland has a negative rate. It helps to be a remote island.

The most intriguing suggestion in the World Happiness Report is that some links between Covid-19 and happiness operate in both directions. The authors do not suggest that happiness helps countries resist Covid-19. Rather, they argue that one of the things that sustains national happiness also makes places better at dealing with pandemics. That thing is trust. Polls by Gallup show that many of the places that have coped best with Covid-19, such as the Nordic countries and New Zealand, have widespread faith in institutions and strangers. Large majorities of their inhabitants believe that a neighbour would return a wallet if they found it.

Countries have failed to see off Covid-19 for many obvious reasons. Some are poor; others are poorly led. They lack recent experience with diseases such as sars. They cannot police their borders.

Importantly, the report also finds differences within nations and across them in terms of life satisfaction mostly related to age: older people report higher life satisfaction in aggregate than do younger people.

Globally, 36% of men over the age of 60 said they had a health problem last year, down from an average of 46% in the three years before. Among women, the share with health problems fell from 51% to 42%. Old people probably are not actually healthier. Rather, Covid-19 has changed the yardstick. They feel healthier because they have dodged a disease that could kill them.

Meanwhile the young have had a rough year. Many lost their jobs—in America the unemployment rate for people aged 20 to 24 shot up from 6.3% in February 2020 to 25.6% two months later (it fell back to 9.6% last month). In some rich countries young women have had a particularly hard time. They often work in sectors, such as hospitality, which have been shut down. When schools close, many are lumbered with more than their fair share of child care.

The United States emerges as a bit of conundrum in the report, given its poor handling of the pandemic overall, with more than 500,000 excess deaths, its low levels of social and institutional trust, and its relatively less generous social welfare programs by advanced economy standards.

Maybe this report is missing something? Arguably, this is only one measure of happiness and we have other data to suggest that Americans are not entirely chipper these days. For example, direct measures of personal happiness from the General Social Survey are at historic lows: only 14 percent of Americans in 2020 said they are “very happy”, although most people remain “pretty happy” and views of personal financial situations are now at an all time high in this same survey.

Likewise, mental health issues are up sharply, particularly among young people, women, and those with lower incomes. And, of course, our politics are as polarized as possible.

Americans remain deeply divided in partisan terms, and across a range of social and cultural issues facing the country. People are constantly amped up against one another online while corporate media and advocacy groups fuel nonstop division and mutual loathing for profit or political gain.

But as the saying goes, “Twitter is not real life.”

The increasing life satisfaction for Americans in the World Happiness Report makes sense if you think about the big picture this question examines. Despite serious and ongoing problems for many people in the country, and widespread divisions and distrust, Americans on average feel pretty good about their position on the ladder of life—almost as good as those in other countries with far fewer people, more social trust, and more generous governments, and a lot higher than those in other countries with lots of people and far greater political dysfunction.

America is pretty darn good place to be if you step out of the miasma of despair and anger in our politics. We have a great country, and if we try to work together amiably on real challenges, we should be able to produce increasing happiness and prosperity for more people.