Corporate America makes a bad bet on Beijing

A shaky moral and economic foundation lurks beneath the shiny 2022 Winter Olympics façade

Let the games begin: the Olympic torch has lit the cauldron in Beijing, and the next two-plus weeks will be packed with all sorts of winter sports – some you may have never heard of like skeleton (check your local listings).

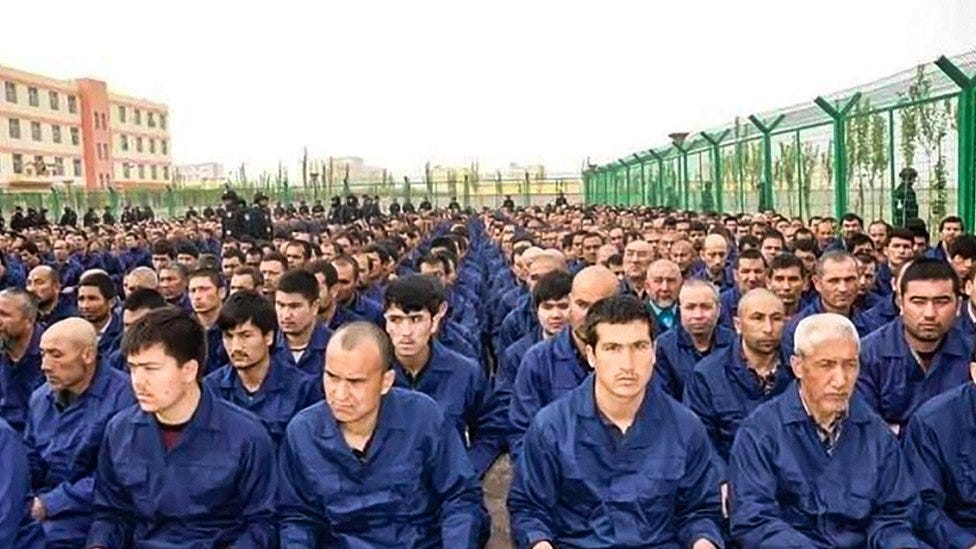

You’ve probably heard about America’s diplomatic boycott of these Olympics – no U.S. government officials are attending in a symbolic gesture to express disapproval about China’s genocide against the Uighurs and other ethnic and religious minorities in the western part of its country as well as other human rights abuses ranging from mass surveillance and detention to slave labor and forced sterilization.

That’s just a short list of wider problems with the ruling Chinese Communist Party and its campaign to suppress freedoms at home and abroad, including extraterritorial censorship, an ongoing crackdown on freedom in Hong Kong, and continued bullying and military threats against Taiwan.

The Biden administration’s diplomatic boycott of the Olympics was joined by other countries, but it’s unlikely to have any meaningful impact on the Chinese government in part because of the way Beijing has been woven into the web of networks that make up the global economy. This entanglement presents extensive challenges to open, democratic societies that host large multinational corporations that seem to care more about the bottom-line profits than any particular national interest or set of values.

China’s regime would like to teach the world to sing – to its autocratic tune

More than 50 years ago, just before President Richard Nixon’s famous trip to China, the Coca-Cola Company had a television marketing campaign that expressed a “kumbaya” ethos of America’s late 1960s and early 1970s culture, centered on this particular ad:

I’d like to teach the world to sing in perfect harmony

I’d like to buy the world a Coke and keep it company

Flash forward to today, and Coke has a different tune: it is one of the biggest corporate sponsors of the Beijing Olympics, a fact that it proudly advertises in China remains more muted about in America. This dual-track approach is one many large corporations with deep ties in both countries have started to take as divisions between the United States and China grow, but it ultimately may become too difficult for them to straddle the geopolitical divide and present different faces – but that depends on in part on how much people care and pay attention here in America.

Private corporations are primarily geared to create value for shareholders by making profits, and the world is filled with corporations that don’t worry so much about the common good and operate like chameleons in different contexts. But when those corporations have such a large effect on the economies and cultures of open societies, it’s worth raising the question of how much true value is generated in a wider sense from the alignment of their interests with those of a regime that is ultimately antithetical to freedom and open competition.

Emerging questions about China’s long-term economic prospects

One other aspect that multinational companies need to keep in mind is not only the moral values and reputational risks questions – but also the prospects for long-term returns on their investments. In the bigger picture, the case for engaging in China’s economy is pretty obvious – it’s a large country that has grown over time. Since China hosted the 2008 Olympics, its economy has grown from $4.6 trillion to $18 trillion in 2021 – and its middle class has gone from 3 percent of the population to 51% in 2018.

But past performance is no guarantee of future results, and some signs of weaknesses could undercut China’s economic prospects in the long run, including:

Growing restrictions on private enterprise;

The risk of falling into the middle income trap;

A massive debt-fueled property bubble;

An aging population that leads some to ask whether China it will get old before it gets truly rich;

A zero-COVID approach that risks China’s economic prospects.

Large companies may look at China’s sheer size, ignore some of these factors, and figure that they could lock in some profits in the short-term, no matter what, but this raises bigger questions about the impact that these companies ultimately have on the bigger picture dynamics in the world.

You must remember this…

It’s always dangerous to compare the current geopolitical moment to previous eras. There was certainly a wave of those comparisons a few years ago during the 100th anniversary of the start of World War I, and it’s always particularly dangerous to compare anything in the world today to the 1930s, which had its own unique set of circumstances.

2022 is the 80th anniversary of Casablanca, the classic film of love and personal sacrifice released during World War II – and one that made the case for America’s involvement in the fight clear via the arc of its main character, Humphrey Bogart’s Rick Blaine. This film was in a sense an American propaganda film – it was filmed during the war and the producers had many battles with Production Code censors from the U.S. government, as detailed in Noah Isenberg’s book, We’ll Always Have Casablanca.

Isenberg also highlights the fact that in the decade before the war during the rise of Nazis in Germany, Hollywood film producers often pulled their punches when they portrayed Germany just to maintain market share and make a buck in Germany and parts of Europe. Again, the comparison between the People’s Republic of China today and the Nazi Germany of the 1930s is inapt – but there are some similarities in the broader dynamic of large corporations and major cultural forces shaping their models to fit into two fundamentally different political contexts.

An overarching question about America’s engagement with China

A quarter century ago, the main idea behind America opening up to trade and deeper ties with China was predicated on the notion that by engaging that country in our own prosperous and democratic system, it would produce new dynamics inside of China that would lead its people and government towards a more open economy and democratic system.

The consensus in America today is that particular theory of the case was terribly wrong and misguided. In many ways, the economic engagement with China created new dynamics inside of America that led to America changing its political economy, rather than China’s – the gutting of manufacturing jobs and growing inequalities inside of America from this period of globalization produced new trends in America’s internal politics that are still playing out.

The economic lesson has mostly been learned from this experience, but America’s politics hasn’t yet sorted out a consensus approach on China. The political debate has some clowns to the left and jokers to the right, but those stuck in the middle are working together to forge a new consensus on how America can compete with China. There’s a lot of work ahead on that front in creating a new strategic narrative on China that brings America together. Congress is still struggling to pass a bill that’s aimed at enhancing America’s ability to compete with China.

The Biden administration took the right step in this diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Beijing Olympics, but it’s a very small and symbolic step. As the games go on the new few weeks, a bigger question looms large:

Is America currently setting itself up for a new form of moral rot that mirrors the economic and political damage done by misguided U.S. engagement with China over the past 25 years?