In a Washington Post editorial from 1983, former New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously wrote, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.” This used to be a seemingly uncontroversial idea. However, this is no longer the case.

At the time, Moynihan was referencing his work on the National Commission on Social Security Reform that developed financing fixes for the program and took on long-standing opponents who sought to convince Americans that the national retirement plan was a “giant Ponzi scheme” and that they would never receive their benefits. Moynihan’s larger point in the op-ed was about the ability of Americans to overcome cynicism and distrust to tackle complicated public policy challenges, like Social Security reforms, by first acknowledging basic facts and then working in good faith to overcome challenges that emerged from the facts. He wrote, “There is a center in American politics,” and it rests on the ability of reasonable people to accept and live with the facts and try “to surmount them” in the interest of governing for the benefit of the entire country.

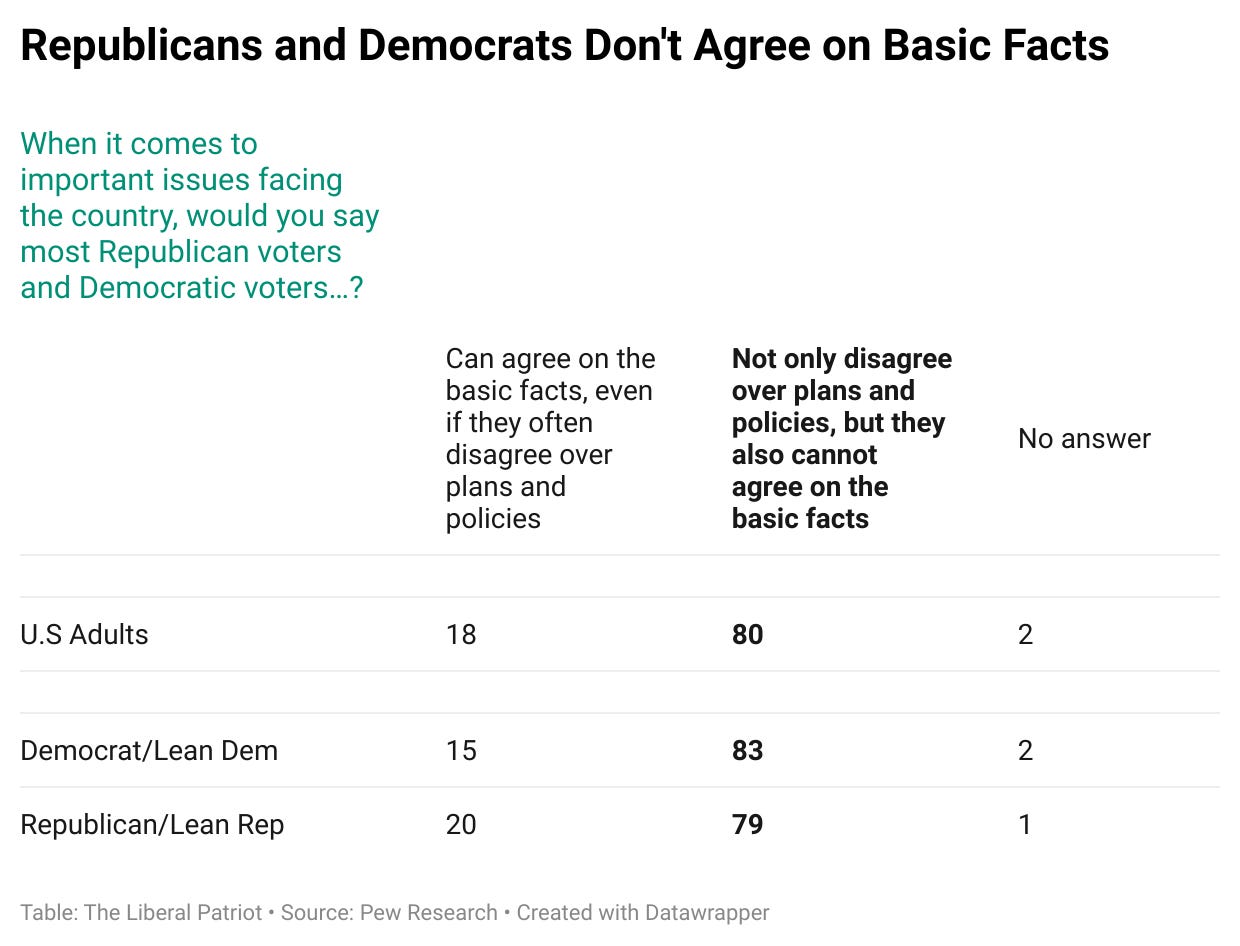

Pew Research just released some sobering data on what Americans today think about Moynihan’s famous dictum. Survey respondents were asked whether most Republican and Democratic voters “can agree on the basic facts, even if they often disagree over plans and policies” or if they “not only disagree over plans and policies, but they also cannot agree on the basic facts.” As the table below shows, an overwhelming eight in ten U.S. adults feel that voters of the two parties cannot agree on basic facts and not just policy ideas, including roughly equal proportions of both party supporters.

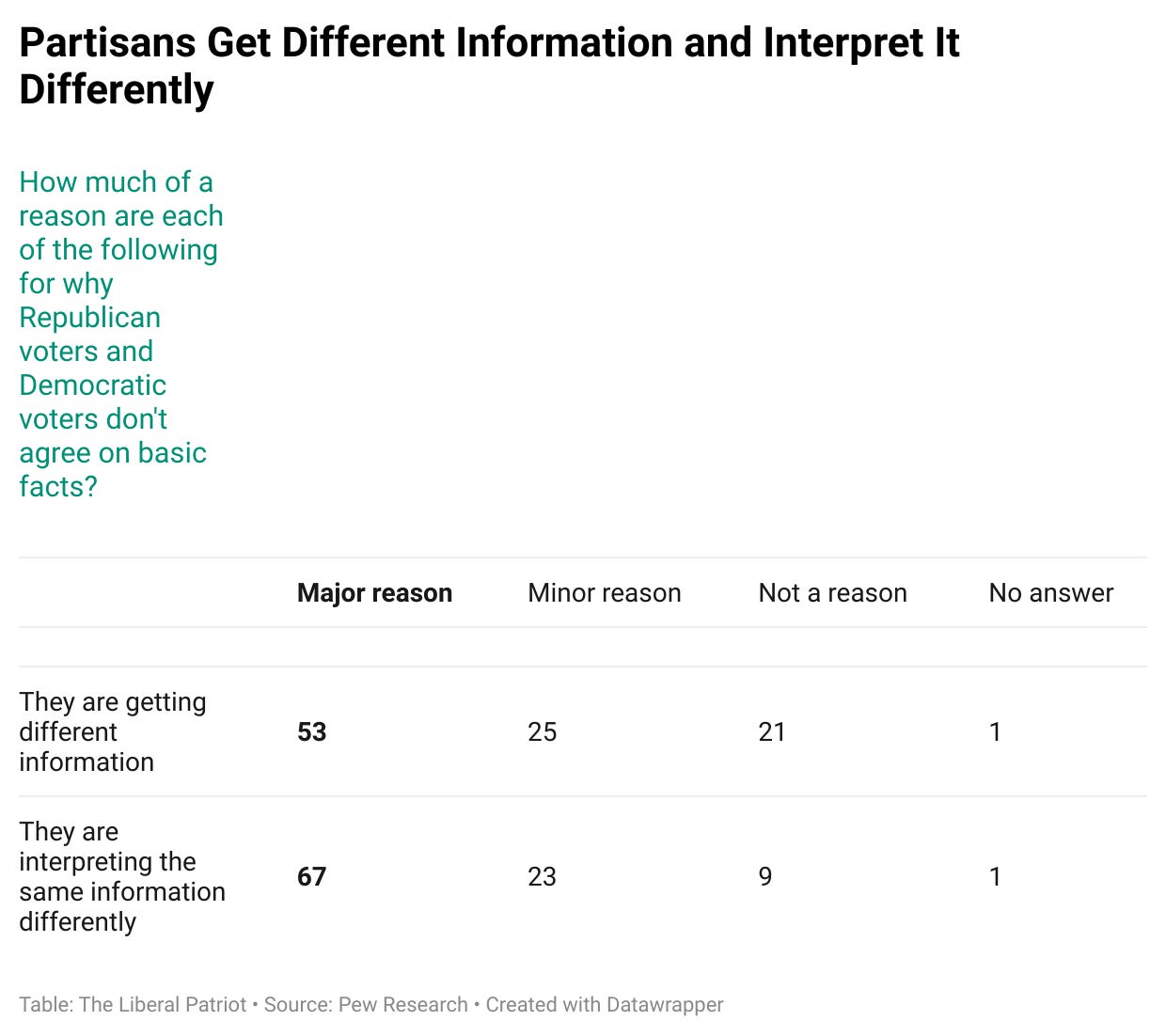

In follow-up questions asked of the 80 percent who said voters can’t agree on basic facts, more than half (53 percent) said a major reason why Republicans and Democrats don’t agree is that “they are getting different information,” while more than two-thirds (67 percent) also said a major reason is that “they are interpreting the same information differently.”

This first finding suggests, more pessimistically, that many Americans believe other citizens are living in “alternative realities” with their own competing facts, while the second finding suggests, more optimistically, that people may be seeing or experiencing the same things but deriving different meanings and conclusions from these facts.

Either way, these results present a serious challenge to Moynihan’s ideal of a broad center in American politics coming together to discern the best policies and approaches based on shared foundations and facts.

To parse out whether we’ve entered a fact-free political environment—or instead, heightened contestation over the relevance of certain facts, what they mean, and how they should be applied in policy terms—we first need to ask, what is a fact?

Basically, a fact is something that can be proven to be correct through observation, measurement, experience, or experimentation. Facts are accepted by most people as true and verifiable information, although facts can and should be disputed honestly and updated when new evidence emerges.

In a court of law, the “facts of a case” often involve whether an event happened and can be proven to have happened, or if it didn’t happen and can be shown by observation or experience not to have occurred (e.g., “The defendant was standing alone on the corner of Main and Central at 12:45PM on August 6, 2024”).

Many times, facts are disputed, and the “truth” is difficult to establish, even in criminal courts. In the judicial system, disputed facts and events without rock-solid evidence one way or the other often lead to charges being dismissed. There is a mechanism and set of rules for adjudicating these matters. Judges give jurors instructions on how to weigh the facts and evidence and apply the law.

But on other matters in public life—particularly historical events, social trends, and public policy measures that make up politics—disputed facts and conflicting interpretations of these facts can only be adjudicated through democratic means of investigation, deliberation, voting, and elections. Here trust matters a great deal. If people don’t trust the sources of information that undergird political debates or don’t trust the interpretations of facts offered by various experts or political officials engaged in these debates, then it’s very difficult for rational, consensus-based policy making to occur as envisioned by Moynihan.

Much of the time, Republicans and Democrats agree on the basic facts of a specific problem or issue and what needs to be done to address it. Many bills in Congress or decisions by the executive branch are passed and enacted without controversy or dispute. Think of recent steps to fight the drug crisis or fund the military.

However, modern politics involves a series of big issues that divide people on both the facts and the interpretations of these facts: think the Covid pandemic, inflation, economic inequality, climate change, crime, and immigration. Unlike the consensus issues above, trust about the underlying facts on these big divide issues is at an all-time low in American politics. Why? First, common facts are difficult to establish and agree upon given partisan considerations, and second, interpretations of these facts increasingly lead to irreconcilable conflict rather than comity and temporary agreement on solutions. Partisans tell themselves that their side has the “real” facts and correct views, while the other side makes it up and has misinformed opinions.

Why don’t people agree on facts? There is a continuum from relatively benign reasons for factual disputes to more malign and ideologically driven reasons for disagreements.

Errors and misreporting. Sometimes people or institutions in the government, media, or the academy make honest mistakes in collecting information or presenting data and other facts. Those people and institutions with integrity will acknowledge their mistakes and issue corrections and implement fixes to ensure they don’t happen again. Ideally, Americans and their leaders will also have some patience with others and accept that errors sometimes happen, especially when those mistakes come from the “other side,” and give people the benefit of the doubt to correct errors and get things right.

Issue complexity. Another relatively benign source of factual disagreement today is the reality that many issues are too complex to adequately measure or to create factual findings that are deemed mostly correct and undisputed. This isn’t an issue of people making up facts; it’s more about those in politics, the media, and academic disciplines diverging on how best to collect facts or measure them in the first place. The “economy” is the top complicated issue that comes to mind here. Unlike a baseball game, where you have clear stats about hits, walks, runs, stolen bases, and errors (and even new technology to better assess balls and strikes to help make these calls less subjective), the measurement of overall economic growth, job creation, inflation, trade, and other measures requires elaborate data collection efforts and government surveys of employers and consumers that are increasingly difficult to get right.

Likewise, the intricate global context of economic activity and differences across national borders in terms of statistics make many comparisons difficult to produce, along with issues of the “informal” economy that can’t be easily captured by traditional measures. Issues involving poverty and inequality also fall into the hyper-complex bucket with data and measurement issues that are contested.

Disagreements over economic and social facts are often real and grounded in genuine challenges and differences in how to look at the economy. And sometimes the disputes are for political advantage. For example, Trump’s recent firing of the BLS head after “bad” job numbers raised genuine issues about data collection and revisions by the nation’s leading economic statistics agency as well as legitimate charges of the president and his party allies “shooting the messenger” for delivering unwanted findings and desiring personnel to produce and interpret data in more favorable ways.

Groupthink. Moving into the less benign side, sometimes people or institutions are too set in their ways, too lazy, or too dedicated to the belief that the facts fit a particular pattern to discover, or even acknowledge, changes in the evidence, outliers, or factual shifts. Again, honest leaders and institutions will challenge themselves and others to avoid groupthink, but, of course, this doesn’t always work. Conversely, ideologically driven groupthink is particularly pernicious these days. Think of the worst public health pronouncements and regulations from scientists and government officials during the Covid pandemic, or people on one side of the ideological spectrum rushing to accept a new “social trend” that advances the party agenda because that’s what other people in their circles believe or what activists demand everyone believes for political purposes.

Partisan spin and purposeful deception. Now we’re into the really bad side. Willful lies and distortions of facts are increasingly the source of many political controversies over issues, leaders, and party agendas today. Think obviously cherry-picked data, false or out-of-context quotes in the media, avoidance of difficult facts that undermine party lines, and outright manipulated evidence and data to advance a party’s agenda. If a party or politician wants something to be true, he or she can often get the entire party and its media apparatus to go along with the deception to push fictions and obviously misleading interpretations as facts. Likewise, if partisans want to get Americans to believe the worst about their opponents, the same misleading tactics will work to advance these goals. Facts about issues have become partisan weapons, with interpretations of these facts often turned into moral crusades masquerading as empirical reality.

Outlandish and patently untrue things. This is DEFCON 1 of “alternative facts.” The land of conspiracies, crazy fabrications on social media, fake videos and pictures, made-up events, alternative histories, AI slop, and a host of other fictions presented as facts. Americans used to be able to just write this stuff off as the output of kooks, mentally ill people, and those on the fringes. But unfortunately, the fact-free fantasies of extremists on all sides—aided by rogue actors, tech companies, foreign governments, and online bots—are increasingly driving the political fights and policy decisions of the U.S. government today.

If a person wants to get closer to Moynihan’s vision of fact-based disagreements on policies carried out in good faith with opponents, what should they do?

On the factual front, a concerned citizen must dedicate serious time to finding and reading the most reputable and long-standing sources of information from government, the media, and the academy. It’s not all partisan hackery. Part of this research should involve absorbing proven, trustworthy, and honest data collectors and analysts across the partisan divide and from the independent world—the “straight shooters.” This is increasingly a huge pain to do given how much information is out there from myriad sources. Normal Americans don’t have a lot of time to suss out every bit of information they consume and therefore must rely on others to do some of this for them. Sometimes these intermediaries and middlemen are honest and trustworthy. Sometimes they are not. Maybe AI will improve to a point where the results of factual queries can be relied on to scour these various sources and present reliable facts to readers or highlight areas where the facts are disputed based on reasonable limitations. Until then, we’ll have to rely on ourselves to do the legwork in obtaining correct factual information.

On the interpretation front, regardless of where one gets their information, they should always double-check the figures and quotes they read and look for obvious errors or inconsistencies that aren’t mentioned. Ask, what was left out in this article? Is this chart calibrated correctly and showing the proper data? Are the differences reported statistically valid or just random? Are there multiple people interviewed for a perspective on an issue? Are these people disinterested parties, or are they committed to a particular point of view? Are the facts presented in the piece mostly neutral, and is the thrust of the argument based on a fair reading of the evidence?

Above all, citizens, and especially partisans, really need to challenge themselves and their leaders to play it straight on the facts and get their interpretations correct. It doesn’t serve anyone’s long-term interests to routinely make up stuff or manipulate factual information for short-term gain. Likewise, downplaying doubts or criticisms about the use of facts for partisan purposes is a big reason why we’re in a world where 80 percent of Americans believe that voters can’t agree on basic facts.

Moynihan had it right. In American democracy, everyone is entitled to their opinions, their favored policies, and their informed criticisms of other partisan or ideological approaches. But these disagreements are infinitely more productive and less combative when Americans and their leaders engage in honest conversations about different ideas based on commonly accepted facts rather than lies, manipulations, and distortions for partisan gain.

All well said.

Whatever you do, just don't let social media be your source of information. My rule of thumb is to favor primary sources when possible, (want to know inflation trends? Check the CPI or PCE, not Twitter) then favor high-end publications with an international lens (Economist, looking at you), then, when you want to get the overtly liberal or conservative take, read the smart guys. The National Review and the Claremont Review of Books (the latter more MAGA populist-ish, the former more old-school William Buckley) will give you legitimate conservative arguments rather than hysterics and strawmen, and for the leftist lens the Atlantic or the New Yorker is worlds better than slop like, I don't know, Salon.

Unfortunately, for the populace at large, more and more people just find it's just easier to live off the algorithmic social media morphine drip and its ideological bubbles. For sure, it's comfy there. Every piece of information that doesn't favor your preconceived notions and the narrative you want to hear is suppressed, every piece that does is amplified. You get to turn your brain off. You get to call anything that makes you uncomfortable 'fake news' or 'Russian propaganda'. But you're actively making society worse when you do it.

I think that train has left the station. It is a spiral where the bubbles grow ever more impenetrable. You missed the most important source of different sets of facts. That is when the media decides what is newsworthy or not. If it is they cover it. This process has been corrupted for partisan purposes. If an issue gets coverage, people can try to suss out facts. If there is just silence, who knows. Traditionally, the MSM made this call. Think back to when they just ignored the ongoing genocide of Indians (as they are called south of the Rio Grande) until Russell Means shamed them into it. Today they would just double down. This sort of thing has led to the development of alternatives which cover entirely different things. A sort of reciprocal cones of silence.