How will we remember the pandemic?

Why COVID won’t fade from public memory like some earlier pandemics

Most people today recognize Marcus Aurelius as the Roman emperor whose private philosophical notebook we now know and read as the Meditations. Or they remember him as a character played by the late Irish actor Richard Harris in the 2000 film Gladiator, where he served as a mentor to Russell Crowe’s protagonist Maximus and disapproving father to Joaquin Phoenix’s villainous Commodus. But until relatively recently, however, the single event that shaped the reigns of Marcus and his son more than any other – the Antonine Plague – went mostly unmentioned and largely unknown in modern discussions about the philosopher-emperor.

Indeed, the opening text of Gladiator makes no mention of the smallpox ancestor that historian Kyle Harper estimates killed roughly ten percent of the empire’s population. Instead, we’re told about the chronic border wars Marcus fought with Germanic tribes toward the end of his reign. When the film’s action shifts elsewhere – including Rome itself – the plague is nowhere to be seen, save for one brief line midway through the film. Of course, it’s asking too much for an action movie to dwell on even a pandemic as devastating as the Antonine Plague. But it’s nonetheless noteworthy that the defining experience of the film’s historical setting merits so little attention.

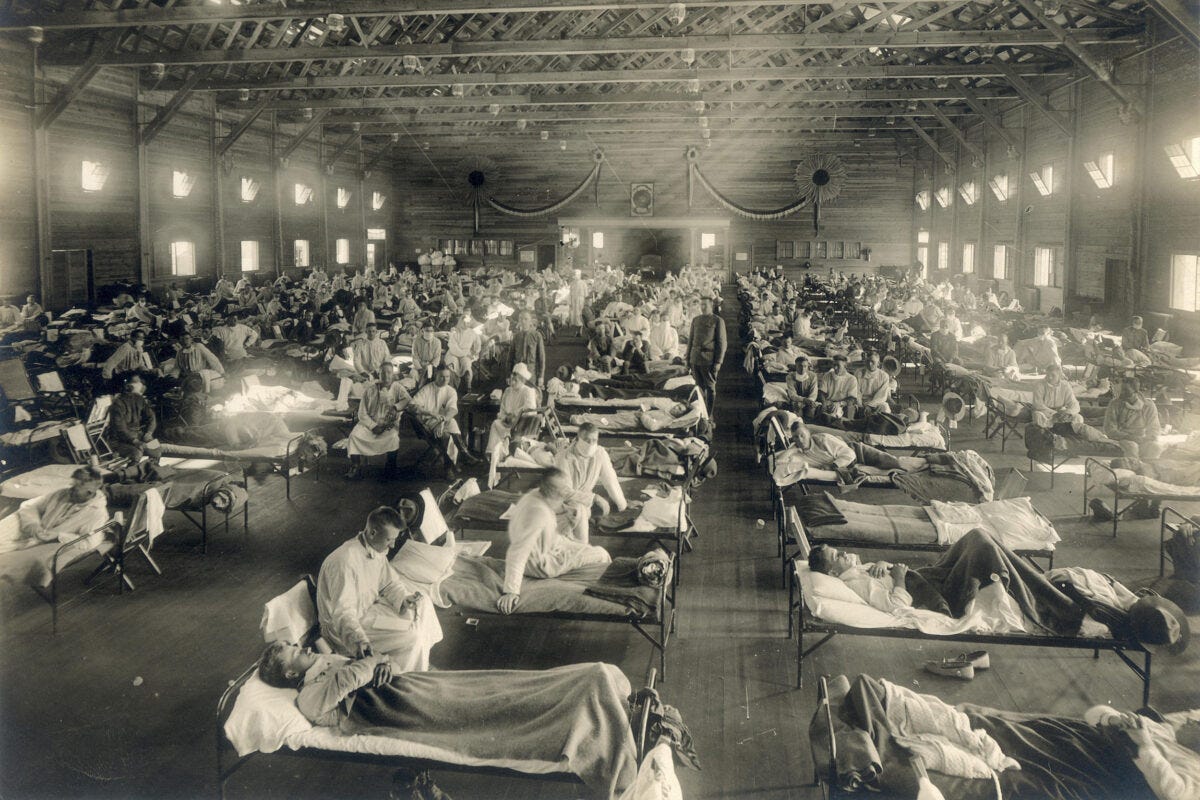

Much the same could be said of the great influenza pandemic of 1918, an episode largely forgotten by the general public until a year ago – even though it left more than 675,000 Americans dead out of a population of roughly 103 million. (That’s the equivalent of over 2 million deaths in America’s current population of around 330 million.) It’s likely that memory of the so-called Spanish flu simply got lost in the shuffle of other cataclysmic events happening at the same time. Indeed, the pandemic’s devastating second wave occurred just as World War I reached its climax on in the fields of Belgium and France in fall 1918. The following year, the United States ratified one amendment to the Constitution – Prohibition – and Congress passed another - women’s suffrage – while President Woodrow Wilson talked peace with world leaders at Versailles and the first Red Scare swept the country.

It’s perhaps not surprising that the tempest of world events overshadowed the 1918 influenza pandemic in America’s public consciousness. After all, the Spanish flu appeared suddenly and then departed just as quickly. Public health and epidemiology were still relatively new fields, and researchers didn’t even isolate the influenza virus until the 1930s. By then, Americans had more pressing problems to contend with at home and abroad: namely, the Great Depression and the rise of fascism.

Other plagues have proven more memorable, primarily due to their perceived historical impact or their persistence. The Plague of Justinian, for instance, has been blamed for the collapse of the Byzantine empire and the rise of the Arab-Islamic empire, though some recent research contends that it may not have been as deadly or profoundly disruptive to the ancient Mediterranean world as previously believed. Then there’s the Black Death, which killed as much as half of Europe’s population over the course of six years in the middle of the fourteenth century and may have spurred the range of social, economic, and political transformations that led to modernity.

What does all of this say about how we’ll remember the COVID-19 pandemic? Will it mark our collective memories in a fashion akin to the Black Death, or largely fade out of public consciousness like the 1918 influenza pandemic?

A year into the pandemic, we can make some educated guesses. As deadly as COVID-19 has been – some 540,000 Americans have died of the disease over the past year – it’s been even more disruptive to the workings of our day-to-day lives. Millions of people have lost their jobs, countless businesses have disappeared with many more on life support, and most schoolchildren have lost at least a year of education. For those of us lucky enough to have experienced a minimum of disruption due to the pandemic, our lives have been in suspended animation for the better part of a year. In that respect, at least, those of us who’ve lived through COVID-19 will recall the more than a year of our lives we lost to the pandemic.

Where the 1918 influenza pandemic occurred amidst a number of profound societal disruptions – world war, revolution and radicalism, and campaigns for women’s rights and Prohibition, to name a few – COVID-19 appeared in an otherwise stable United States. While America had societal and political problems before the pandemic hit – many of which revolved around then-President Trump – none of them rose to the level of widespread national disorder or global turmoil of 1918 and 1919. It’s not hard to see how or why many Americans today might remember COVID-19 more strongly than their counterparts a century ago did the Spanish flu.

Thanks to modern science and medicine, moreover, we already know much more about COVID-19 than Americans a century ago knew about the influenza pandemic – to say nothing of those centuries and millennia in the past who attributed plagues to divine wrath or other supernatural causes. Despite the claims of cranks and charlatans, we’re not fumbling around in the dark when it comes to why and how the COVID-19 virus works at a basic biological level or how it spreads from person to person.

But if future generations remember the COVID-19 pandemic, it’ll probably be because it heralded a major and fundamental shift in America’s domestic political economy. One major reason we still recall the Antonine Plague, for instance, is that it likely set into motion the centuries-long process that ended in the disintegration of the western Roman empire. The Black Death remains in a class of its own, its sheer scale enough to throw any society into existential disarray. It’s already clear that COVID-19 won’t likely have similar effects on American society, but all the same it’s accelerated the country and its politics beyond the model of political economy that’s prevailed since the late 1970s.

Forged by policymakers and politicians scarred by their experiences with stagflation in the 1970s, that model of political economy focused intently on fighting inflation and reining in federal budget deficits – except when it came to cutting taxes for the wealthy. A typical episode occurred in 2015, when the Federal Reserve under then-Chair Janet Yellen – now President Biden’s Secretary of the Treasury – raised interest rates amidst a still-weak recovery from the 2008 financial crash in order to ward off the phantom menace of potential inflation. Likewise, President Barack Obama found it politically necessary to find ways to ensure his signature legislative achievement – the Affordable Care Act – essentially paid for itself through tax increases, budget cuts, and other offsets.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, though, the wheels had started to come off this model of political economy. Persistently low interest rates even amidst large and sustained budget deficits throughout the 2010s led a number of economists and policymakers to conclude that their earlier ideas were outdated, if not outright wrong.

But it took the pandemic to truly shift the mindset of political leaders and policymakers in Washington. As COVID-19 made its way to the United States in February and March 2020, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell opened up a “fire hose of lending” intended to keep the economy afloat. Over the past year, Congress has passed pandemic three major relief packages – the CARES Act in March 2020, a $900 billion bill in December 2020, and the American Rescue Plan Act this month – worth a combined $4.8 trillion and one of the world’s largest fiscal policy responses to the pandemic. Even so, Powell repeatedly called for more public spending to support the economy – and has given no indication that he intends to take his foot off the economic accelerator any time soon, saying that the Federal Reserve “will continue to provide the economy the support that it needs for as long as it takes.”

Muted and incoherent Republican resistance to President Biden’s relief legislation should be seen as a sign of the changed political times. Unlike the concerted effort to derail and then discredit the Obama administration’s post-2008 Recovery Act, Republicans and conservatives have proven unable to muster any real arguments against the American Rescue Plan. Indeed, shortly after the law passed a number of Congressional Republicans took to social media to tout provisions of a plan they’d voted against.

Thanks to this tectonic shift in politics and policy, moreover, a number of economic forecasts predict the U.S. economy will grow at a faster rate this year than at any year since 1984 – equaling or even surpassing Chinese economic performance in the process. Ironically enough, it’ll also help the Chinese economy as American demand for global goods picks up along with our domestic economy. But a strong U.S. economy also benefits our neighbors in Canada and Mexico, as well as allies in Europe and East Asia like the UK, Germany, and Japan. More importantly, though, a swift recovery from the pandemic will demonstrate that democracy can still deliver for its citizens when it counts.

That’s all the more important after four years of President Trump and amidst a global democratic recession that dates back a decade and a half. It also goes to show just how important effective American domestic policies are to the fate of freedom around the world. Recovery from COVID and its severe economic consequences will embody what President Franklin D. Roosevelt called the “soundness of democracy in the midst of dictatorships” – a concrete example that democratic nations do not need to trade freedom for the false promise of security offered by autocrats the world over.

The sense that the COVID-19 pandemic inaugurated a new era of political economy in the United States will only be reinforced if Congress enacts the massive infrastructure package President Biden intends to put forward. More than that, though, it’ll cement the pandemic as an epochal event in our collective national consciousness. Beyond the countless and varied personal losses it will leave behind, the COVID-19 pandemic will have changed our politics and policies in profound ways. It accelerated the nation and the world at large down political and economic paths it may have taken anyway at a far more leisurely pace, leaving traces and imprints that will be visible well into the future.

While it’s too much to expect that COVID-19 will leave behind a legacy of solidarity and common purpose akin to the Great Depression and World War II, it’s already shifted how many of us think about the role of government and our responsibilities toward our fellow citizens. That may not be apparent amidst the discord we’ve all seen and heard over the past few years, but it’s present – and it’s something liberal patriots should aim to build on moving forward.