A sobering Financial Times analysis from this past weekend by John Burn-Murdoch examines the rise in early deaths among middle-aged people across advanced countries, most notably in the United States, the UK, and Canada, even as older people are living longer.

Why are people in English-speaking countries today dying younger?

Burn-Murdoch gets under the hood of the much-discussed “deaths of despair” research to ascertain which specific factors are contributing the most to higher mortality rates for younger people. He argues:

But more recent research, which followed thousands of adults in the US over several decades, found that the “despair” framing is not quite right. What marks out those who succumb to self-destructive behaviour is not psychological distress or financial hardship—specifically, it is long-term joblessness and social isolation.

My analysis of middle-aged mortality on both sides of the Atlantic confirms that an equally simplistic narrative of “it’s just the availability of drugs” is only part of the story. Deaths from substance abuse have not risen uniformly across the population; they affect specific cohorts of people who were hit by large negative employment shocks in early life. This is most pronounced in Scotland, where the bulk of deaths from drugs and suicide have afflicted the generation that grew up during spells of high joblessness during the rapid deindustrialisation of the 1970s and 1980s.

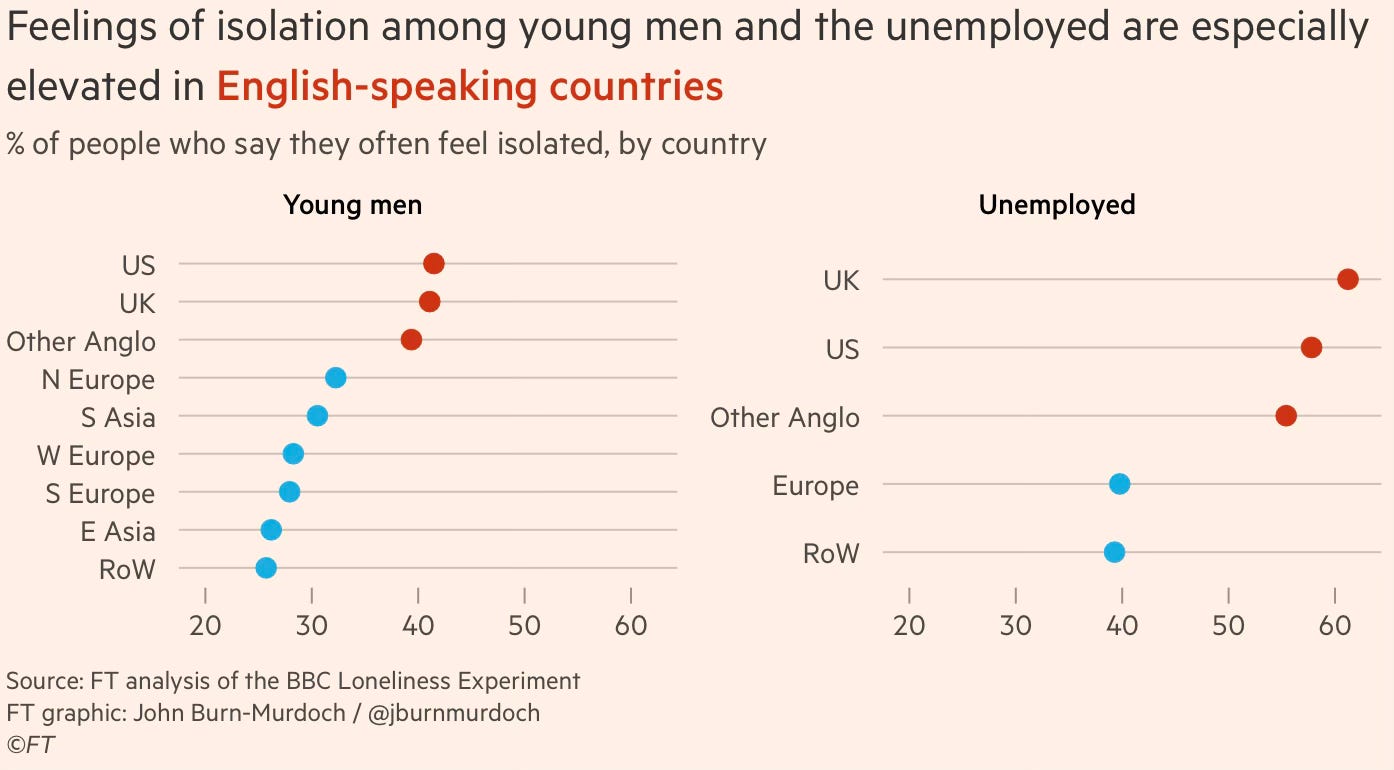

But drugs and economic dislocation aren’t enough on their own, either. Many countries in western Europe with fentanyl in circulation have endured bouts of unemployment almost as severe without the subsequent waves of mortality. Separate data highlights the final piece of the puzzle: both young men and people out of work report being significantly more socially isolated in English-speaking countries, markedly increasing the risk of self-destructive behaviour. Several factors in non-anglophone countries may be playing a protective role here, from levels of religious belief and social solidarity to more concrete factors such as close-knit multigenerational family units. These may allow other populations to weather storms that damage anglophone societies.

As mentioned in the article, looking at the BBC’s Loneliness Experiment research conducted with more than 55,000 participants, Burn-Murdoch finds the challenges of social isolation are most acute among younger men and the unemployed in English-speaking countries, with joblessness producing sharper feelings of isolation than age and gender combined, as seen in the charts below.

The BBC study also examines the prevalence of loneliness, a complementary but distinct concept to social isolation, and finds that younger people report the highest levels: “40 percent of 16- to 24-year-olds who took part told us they often or very often feel lonely, compared with 27 percent of over 75s. We saw higher levels of loneliness in young people across cultures, countries, and genders.” It’s important to note that compared to social isolation, which is more objectively measured through things like living alone or not having much contact with family, friends, and others, loneliness involves more subjective sentiments such as “feeling disconnected from the world,” “feeling left out,” “sadness,” or “not feeling understood.” People can live alone and be somewhat socially isolated without feeling lonely—many people prefer to do things on their own without any negative life consequences whatsoever. Often it’s a matter of degree on these issues, with people who spend too much time alone or being too isolated ending up in worse spots. In turn, high levels of social isolation and loneliness lead to lower levels of interpersonal trust and poorer physical and mental health that may contribute to an early demise.

The BBC research includes self-selected participants in its methodology, so keep that in mind when assessing relative causation. It’s easy, however, to see how a combination of factors described above—not working, not being in contact with others, feeling lonely starting at a younger age—could drive much of the increased mortality data for middle-age people that is firmly established.

Given these trends, the more important question then becomes, what can we do about it, if anything?

With good reason, many people prefer that governments do not interfere with their work, living circumstances, or personal beliefs and feelings. But governments certainly could do more to make long-term joblessness, social isolation, and loneliness, particularly among younger people who are most affected by these conditions, specific priorities for public policy development.

On the economic front, national and state governments can and should do more to develop and implement place-based strategies to aid distressed communities, as TLP contributor Tim Bartik has written about extensively. By targeting resources to increase employment and improve wages in places struggling with declining industry or underdevelopment, national and state governments can help local officials overcome weak tax bases and limited funds for investment in education, transportation, public spaces, and health care systems. Since most people prefer to stay in their communities rather than move somewhere else for work, flexible place-based strategies tailored to local contexts can help employers, workers, and families all do better, thus reducing long-term joblessness or underemployment and combating rising social isolation and perhaps even loneliness.

On the social front, national and state governments can and should do more to promote pro-family policies and other communitarian efforts. People growing up with intact and economically stable families throughout early adulthood will be better prepared and supported when starting out their own lives and careers—and hopefully be less socially isolated or lonely. Government tax supports or childcare assistance for working parents with children along with efforts to reduce housing costs are two clear ways to encourage more economically stable families. Likewise, governments can direct more resources (in an equal and constitutional manner) to faith-based groups and other local volunteer-based organizations that help bring people together within supportive communities that matter to them. National, state, and local governments can also do far more to reduce crime and social disorder in neighborhoods and improve public spaces and commercial life in more cities and towns, thus encouraging people to get out more and enjoy interacting with others.

On the digital front, governments, tech companies, and philanthropists could seed new projects to increase the potential civic benefits of the internet and social media. Rather than fueling more social isolation and loneliness, digital life could be augmented with real-life gatherings that bring people together to share work or parenting experiences, educational or political interests, common hobbies, and reading or other cultural pastimes that could be pursued in person rather than solely online.

Public policy alone cannot solve all the problems associated with social isolation and loneliness, at least not directly. But governments can make issues of long-term joblessness, isolation, and loneliness serious public concerns and target resources to bolster employment, strengthen families, and encourage social cohesion to ensure all young people are best prepared for the stresses of modern work and family life.

In our highly polarized politics today, these issues seem like a promising area for bipartisan legislation and cross-ideological cooperation.

After all, across different national contexts, the people who live the longest tend to share common traits beyond healthy genes and personal optimism—decent employment, a robust work ethic, good living habits, safe and clean environments, and close family, religious, and other social bonds. Stronger families and communities yield stronger citizens.

In my experience government always winds up exacerbating every social ill it attempts to solve. The only worthwhile policy I see here is controlling crime and disorder which is a core government function. Beyond that I’d recommend:

Focusing like a laser on promoting economic growth and a hot economy.

Getting K-12 education back to basics. I.e. Stop trying to implement the latest Ed school fad and focus on reading, writing & arithmetic in primary schools. Bring back vocational education in junior high and high schools so kids who aren’t going to college graduate with marketable skill sets.

Beyond that this is about culture. Government should stay out of it, because government trying to affect culture is probably what got us here in the first place.

The most important thing to realize about Northern Europe is that despite low rates of marriage, they are an extremely monogamous culture. Andrew Cherlin points out in The Marriage Go-Round that unmarried couples in Sweden are less likely to separate then married couples in the USA.

Male loneliness is all downstream of promiscuity. Even if you aren't particularly red-pilled (in the OG sexual reality sense), here is the dating market:

* 22 year old men (either blue collar or post-college): women who are 22 or perhaps a bit younger

* 22 year old women: men who are 32ish and younger

But it changes when you hit 30:

* 30 year old men: women in their 20s

* 30 year old women: men in their 30s who haven't yet married

When I was in my younger 20s I was largely invisible to women because I'm not a bubbly extrovert. But as my 30s approached women started making themselves available, and oftentimes chased me. I think for women, more than merely "hitting the wall" at age 30, is the reality that the good men are rapidly marrying out of the dating market. Most women don't want to be the last one standing when the music stops and the good men are all married.

The upshot is that young men spend their 20s drifting. Hookup culture, pot, video games, anime. They don't have a family to work for, so unless they're unusually driven, their career is not important. They have no purpose, no mission. High school friends have a way of scattering, but even if they stay close, hanging out with friends drinking beer and playing video games does not satisfy the longing for love and connection. I personally spent much of my 20s as a snowboard bum, and then at some point in my late 20s, a little alarm went off and I moved back to the East coast and got my first full-time job. I was married a couple years after that.

Edit: This was perhaps the largest part of Charlie Kirk's ministry to college students. You get out of life what you put into it, and young men who start living with purpose and break free of hookup culture, drugs, or porn can move their life in their 20s to a very different track.