Lighter Than Air—and Common Sense

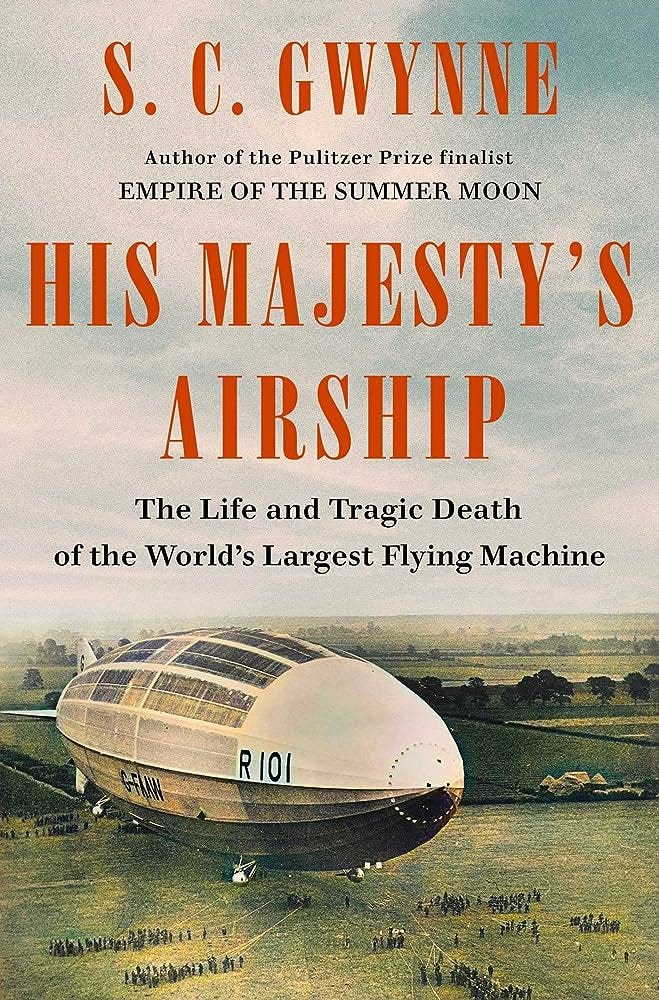

A review of "His Majesty’s Airship: The Life and Tragic Death of the World’s Largest Flying Machine"

On the dark and stormy night of October 4, 1930, the giant British rigid airship R101 plowed nose-first into a farm field in northern France and burst into flames. Forty-eight members of the airship’s crew of fifty-four perished in the conflagration, making the disaster even deadlier than the Hindenburg catastrophe seven years later. Among the dead was Secretary of State for Air Lord Christopher Birdwood Thomson, the architect of and chief evangelist for Britain’s ill-fated rigid airship program. Largely forgotten today, the R101 disaster has much to tell us about how industrial policy gets made—and how it can go horribly wrong.

It's a story unearthed and ably told by journalist and non-fiction author S.C. Gwynne in his book His Majesty’s Airship: The Life and Tragic Death of the World’s Largest Flying Machine. Moving back and forth between an account of Britain’s quixotic airship program and the progress of R101’s fateful maiden voyage, Gwynne’s taut narrative comes together as the airship plunges from the skies above Frances and toward its fiery demise. He unsparingly details the folly of Britain’s airship program and fantasies that inevitably drove it toward a tragic end.

Lord Thomson sits at the heart of Gwynne’s narrative, “a man obsessed” with the notion that rigid airships could “connect the far-flung outposts of the British Empire through the new medium of air.” A well-connected and ambitious Labour Party politician, Thomson had a story of his own to tell: he offered British policymakers a “gauzy, rainbow-inflected vision of a future in which fleets of lighter-than-air ships float serenely through blue imperial skies, linking everything British in a new space-time continuum.” He was also determined to make Britain the world’s leading airship manufacturer, taking the title away from Germany and its zeppelin-makers.

But rigid airships weren’t the technological wave of the future Thomson and other advocates imagined them to be. From their very inception, rigid airships faced fundamental and irresolvable conceptual problems that made them both impractical and dangerous—problems that ought to have been apparent to any and all observers by the time Thomson won support for his Imperial Airship Scheme in 1924. Early zeppelins were difficult to fly, highly vulnerable to inclement weather, and had a distinct tendency to explode, all issues that would never be fully remedied by any rigid airship design.

Still, the German military saw zeppelins as war-winning weapons and sent them on terror-bombing missions against Britain during World War I. But their intrinsic technological limitations soon revealed themselves: zeppelins were routinely blown off course and regularly missed their intended targets by enormous margins. They eventually became easy prey for British fighter planes armed with incendiary bullets that ignited the hydrogen in their gasbags, and only 44 of 125 zeppelins built survived the war.

Nonetheless, Germany’s zeppelin campaign made an impression on the victorious Allied powers, and each nation embarked on rigid airship trials at war’s end. These experiments went so poorly that they ought to have put an end to rigid airship programs altogether. Fatal disasters piled up one after another in the early 1920s: the British R38 crashed in 1921 and killed all but five of its forty-nine crew members. Six months later in the United States, the Italian-built Roma exploded over Norfolk and left thirty-four dead. France’s Dixmude and its crew of fifty-two likewise went up in flames during a storm over the Mediterranean in December 1923.

Despite this grisly spate of disasters, however, the Imperial Airship Scheme moved ahead—largely on the strength of Thomson’s narrative. He had a story to tell about Britain and its place in the world, one in which airships tied the Britain’s increasingly fragile empire closer together and demonstrated its industrial might. Thomson told this story with the conviction of a true believer in both rigid airships and the British Empire.

But reality couldn’t meet Thomson’s dreams. R101 wound up a practical engineering disaster: too overweight to fulfill its primary function and burdened with a “rotting” linen outer cover and leaking hydrogen gas bags, R101 required extensive modifications to even have an outside chance of completing a trip across the Middle East to Karachi in what was then British India. Nor did the airship have the sort of extensive test flight program that might be expected of an experimental aircraft. R101’s lead engineers knew about many of these problems and discussed them on multiple occasions—only to swallow their doubts whole and proclaim a deeply flawed design airworthy.

Pressure from Thomson to get R101 airborne only made matters worse. He wanted a successful demonstration of his vision, a proof-of-concept that would both advance the cause of rigid airships and his own career. A roundtrip to India ahead of the upcoming Imperial Conference in London would do the trick—and give Thomson an impressive public relations coup as the conference weighed the future of Britain’s airship program. Thomson had started a race against time that, as Gwynne observes, “sometimes looked more like panic.” R101’s decayed and deteriorated cover was literally patched up, and then patched up again, to make Thomson’s aggressive schedule.

In the end, Thomson’s rush to validate and vindicate his airship policies had little to do with R101’s demise—more general issues regarding airship operations and unrelated mechanical problems bear much of the blame. But Gwynne’s narrative makes clear that there was no way the Imperial Airship Scheme would or could have worked as Thomson and other dirigible advocates had advertised. Rigid airships were simply not a viable means of transportation; basic physics conspired against these hulking behemoths and prevented them from flying safely in anything but pristine weather. National airship programs would persist elsewhere—America’s own military rigid airship program would suffer two more fatal disasters before the U.S. government finally shuttered it in 1935—but after R101, the writing was on the wall.

The real mystery at the heart of Gwynne’s account isn’t why so many airship programs failed but why they took hold and then lasted as long as they did. Nations embarked upon these programs despite clear evidence that rigid airships were a dangerous and unworkable technology, more apt to go down in flames and kill their crews than provide reliable air transport or perform necessary military functions. It took repeated disasters and dozens of fatalities to demonstrate that the romantic fantasies peddled by airship boosters like Thomson were horribly wrong—and that rigid airships were a terrible use of national resources.

If nothing else, His Majesty’s Airship dramatically illustrates the power of narratives to shape and determine industrial policy. As Britain’s doomed Imperial Airship Scheme shows, these stories don’t even have to pass basic reality checks if they’re supported by influential and persuasive evangelists like Lord Thomson. More often, though, the tales spun by advocates for various technologies and industries have much larger grains of truth at their core. At worst, they come with a high level of uncertainty about the viability or sustainability of a given technology or industry. Few industries or technologies receiving or seeking government backing today—like, say, electric vehicles and artificial intelligence—have anything remotely like the string of deadly disasters and intrinsic operational difficulties that plagued rigid airships. We ought to expect occasional failures, though certainly nothing on the scale of R101 and the Imperial Airship Scheme. That makes it all the more important that political leaders and policymakers kick the tires of any proposed venture.

When it comes to industrial policy—and indeed all public policy—we ought to apply Franklin D. Roosevelt’s definition of common sense: “Take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”