National Politics Is a Graveyard

An independent movement dedicated to shifting from winner-take-all to proportional representation in legislative elections might be able to resurrect it.

It’s time to face reality: two-party politics has failed. Americans want more and better choices than the ones Republicans and Democrats currently provide. Whether the two-party system stands or gets radically transformed in the future remains an open question, however.

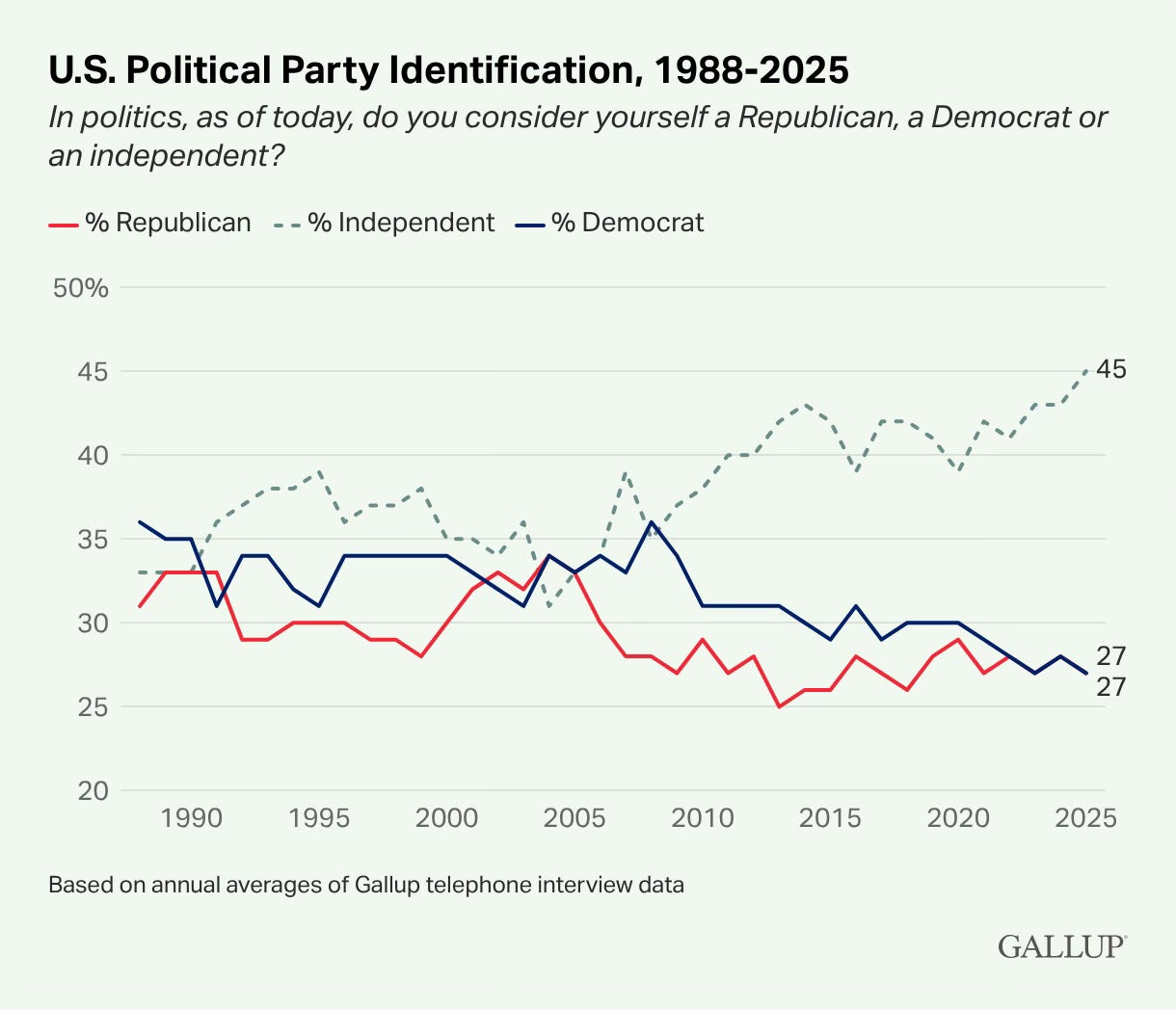

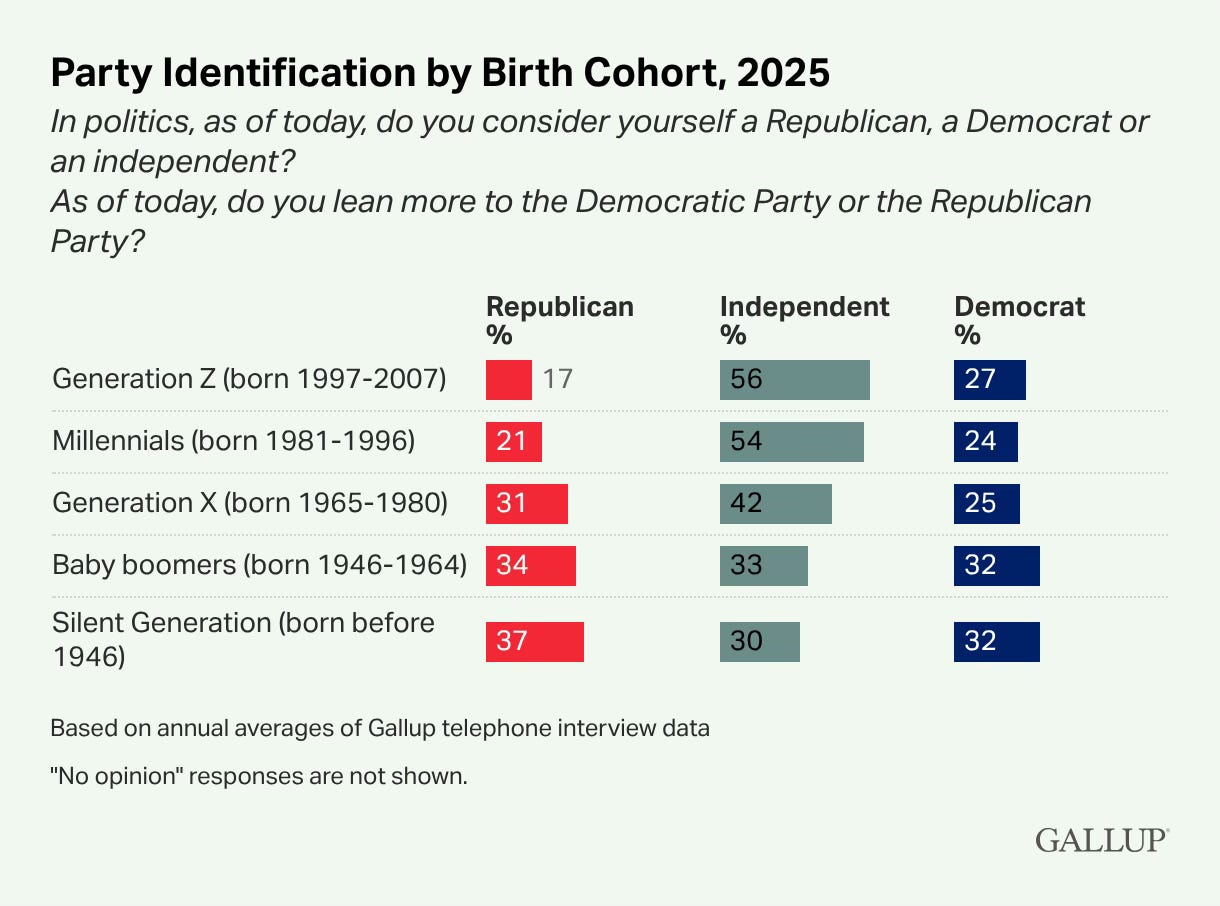

As reported by Gallup, a record-high percentage of American adults at the end of 2025 self-identified as political independents, 45 percent, including majorities of both millennials and Generation Z plus a plurality of Generation X. In comparison, less than three in ten Americans self-identified as either a Republican or a Democrat in 2025, respectively.

People who cling to a fading notion of partisanship often assert that political independence is a youthful phase and that people’s party affinities deepen with age. While this may have been true in the past, Gallup’s numbers challenge the notion going forward—political independence tops partisan identification among every age cohort born from 1965 on.

The recent increase in independent identification is partly attributable to younger generations of Americans (millennials and Generation X) continuing to identify as independents at relatively high rates as they have gotten older. In contrast, older generations of Americans have been less likely to identify as independents over time. Generation Z, like previous generations before them when they were young, identify disproportionately as political independents.

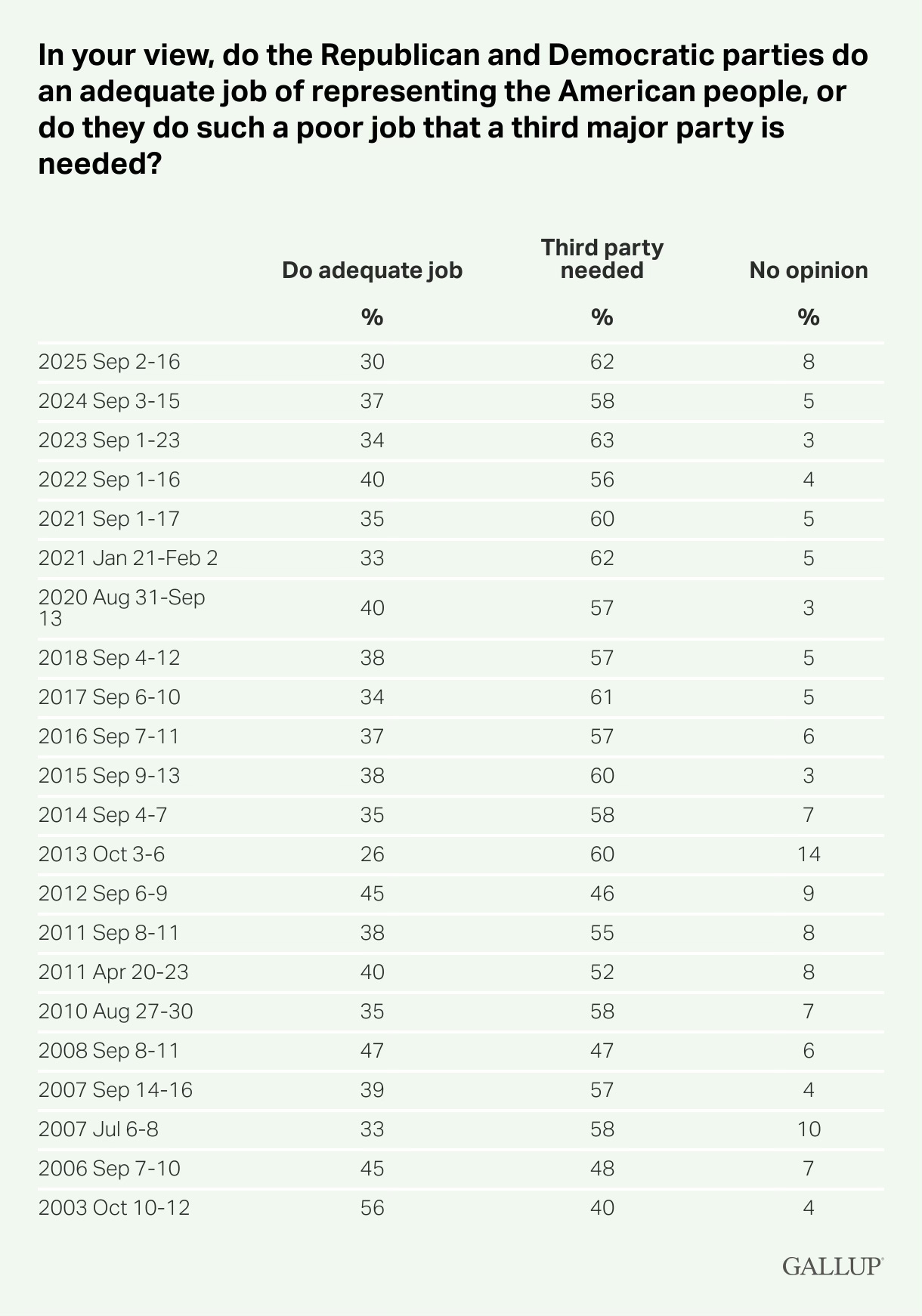

As political independence increases steadily, the desire for a major third party has also climbed. Sixty-two percent of American adults in 2025 said that a new party is needed compared to only three in ten adults who feel that the “Republican and Democratic parties do an adequate job of representing the American people.” In contrast, 56 percent of U.S. adults felt the two parties adequately represented Americans in 2003.

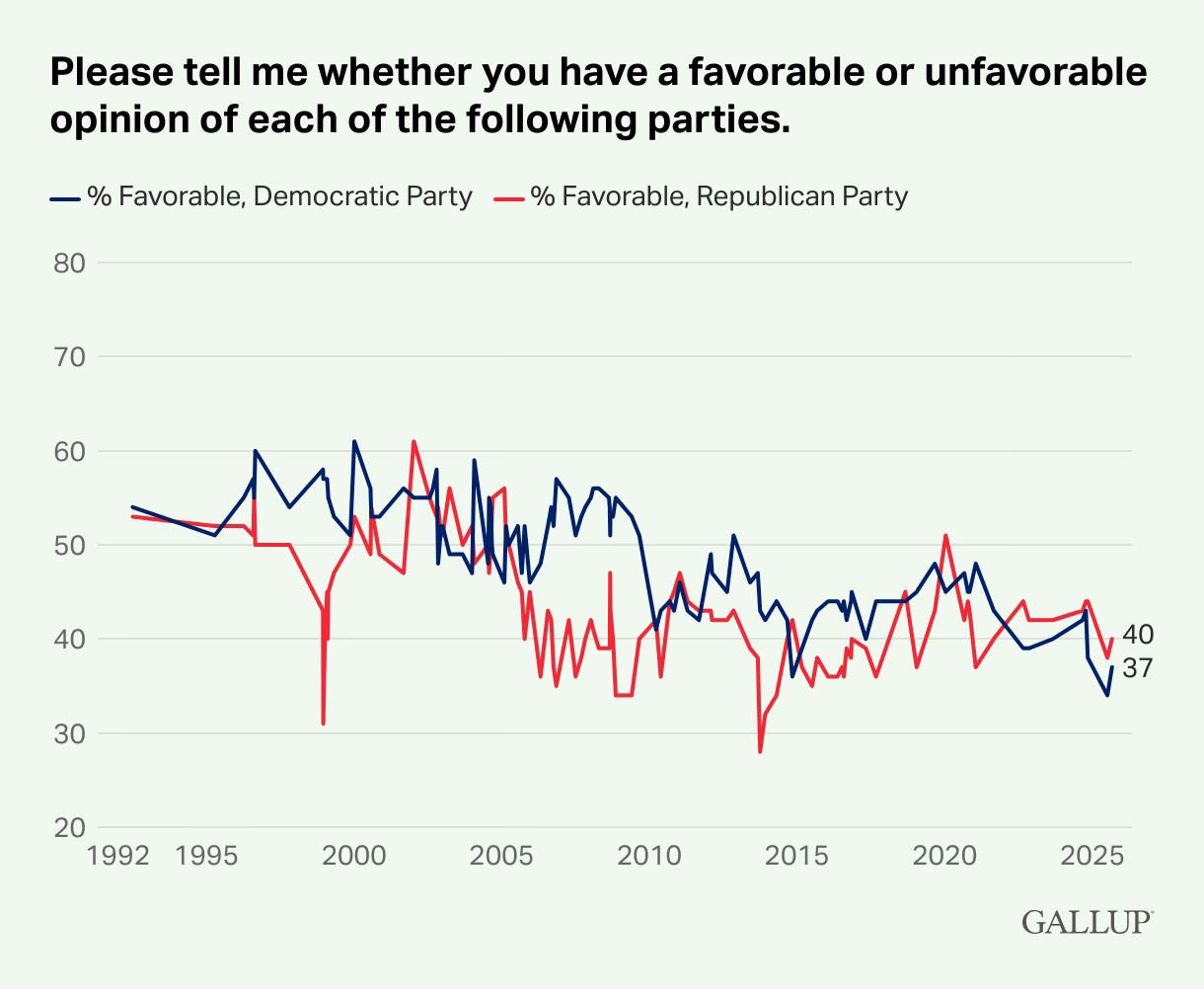

The desire for a third party makes sense when you examine the sharp declines in public favorability towards both Republicans and Democrats. In the early 2000s, more than six in ten Americans held a favorable opinion of both parties at some point. By the end of 2025, only four in ten felt favorably about Republicans, and only 37 percent felt that way about Democrats.

If you look at the trajectories of the last three presidential terms, Trump-Biden-Trump, you can see how disdain for partisanship plays out. In each instance, the incumbent party’s president lost overall public support rapidly as independent supporters sided with the opposition against the incumbent, leading to frequent switches in party control of both the Congress and the presidency. Trump and Republicans came into office in 2017 with unified control of government only to lose the House in 2018 and both the presidency and Senate after the 2020 election. Biden came into office in 2021 with unified control of Congress and promptly lost the House in 2022, and then Democrats lost both the presidency and the Senate in 2024. Trump again started his second term with unified control of government yet looks on track to at least lose the House in 2026.

Who knows what will happen in 2028 at the end of the Trump era? Stability seems unlikely, however.

Neither party seems capable of building nor sustaining durable national majorities. Republican and Democratic leaders and their policy programs are widely disliked by both political opponents and many independents, as they each pursue purely partisan objectives when in power that further polarize and alienate the electorate. Since voters are essentially forced to choose between two failed parties every cycle, the system chugs along with Americans growing increasingly cynical about government and politics.

But if voters were offered an option beyond the two major parties, many Americans would gladly take it up.

Given the amount of money and anger floating around politics today, it’s genuinely puzzling why a viable third party has not started. Of course, with the stranglehold of Republicans and Democrats over election laws and regulations, third parties face enormous hurdles. Likewise, except for Libertarians, third parties tend to organize around mercurial figures like Ross Perot, RFK Jr., or Elon Musk rather than around a concrete set of ideas or a coalition of voting blocs united behind a common purpose pursued over time.

Perhaps the viability of third parties will change in the not-too-distant future. For example, one could imagine a mostly moderate, pro-business, anti-deficit, anti-culture war party emerging to appeal to disgruntled centrists. Perhaps an old-school conservative party might rise to attract ex-Republicans who dislike Trump’s transformations of the GOP, or perhaps a truly social-democratic, pro-labor party could bring together working-class ex-Democrats who disagree with the party’s cultural and economic turn. One could also imagine two fiery left- or right-populist parties cropping up separately (or combined) to challenge the two-party duopoly.

For any of these third parties to have a chance, however, America first needs a strong independent movement dedicated to changing state and federal laws that enshrine two-party politics. As Jesse Wegman and Lee Drutman argue, this means a switch from winner-take-all to proportional representation in national legislative elections, with the creation of multimember districts and the elimination of partisan gerrymandering (and U.S. Senate and presidential elections remaining constitutionally the same).

Proportional representation models vary by country, but basically all of them create a situation where political parties get legislative seats based on the percentage of the vote they receive in a given election, thus encouraging and rewarding multiparty competition. In the American House of Representatives under this scenario, you could hypothetically vote for the populist-right Patriot Party, the centrist Liberal Party, the enviro Greens, or the Christian conservative Family Party, and each would get seats if they meet certain thresholds of support. The House, in turn, would be required to form some coalition of parties to enact laws to send to their Senate counterparts and eventually the president, who would also have to work with more than his own party and the traditional opposition to get things done.

It’s not a perfect system and potentially creates its own problems with stability. But a politics based on proportional representation would certainly meet the American public where they are in terms of their own often complicated views and the limited party choices they get every election cycle.

Change of this nature would require sitting or future members of both parties voting to reform state and federal election laws to allow for proportional representation in the House. America does not need to become a parliamentary democracy to do this or go through elaborate constitutional amendments. Reformers just need some willpower and solid organization to overcome partisan strong-arming and resistance to change.

At some point, a dedicated group of independents and like-minded members of the two parties need to put their heads together, with serious philanthropic backing, to develop a real movement to create proportional representation in America—with policy designs, model legislation, federal and state lobbying efforts, and public communications and voter outreach.

This is a tall order, for sure, but not impossible given the rising public hatred of existing partisanship and politicians themselves seeing the writing on the wall about dysfunctional government. The U.S. Constitution does not mandate a two-party system. Legislative elections can be changed to support multiple parties if Americans and a new generation of leaders choose to do so. Any takers?

In “first past the post” the voters get a clear and unambiguous signal. An “up” or “down” on the party in power. Proportional representation takes that away and dilutes the mandate. It gives leftist institutions, like the media, first mover power to determine what a compromise coalition will look like. What issues will be dropped (border security and abortion) and what will be kept (climate justice). That’s why leftists hate first past the post and advocate for proportional representation.

We won’t always be so polarized. History shows that leftism always burns itself out, at which point left-liberals and classical liberals pick up the pieces and start building again.

"People who cling to a fading notion of partisanship often assert that political independence is a youthful phase and that people’s party affinities deepen with age."

I'm 67 and I find the mindless partisanship emanating from both parties repellent.