No Country for Old Men

America is divided between the optimism of younger generations and the skepticism of older people. Politics needs a better way of blending these views.

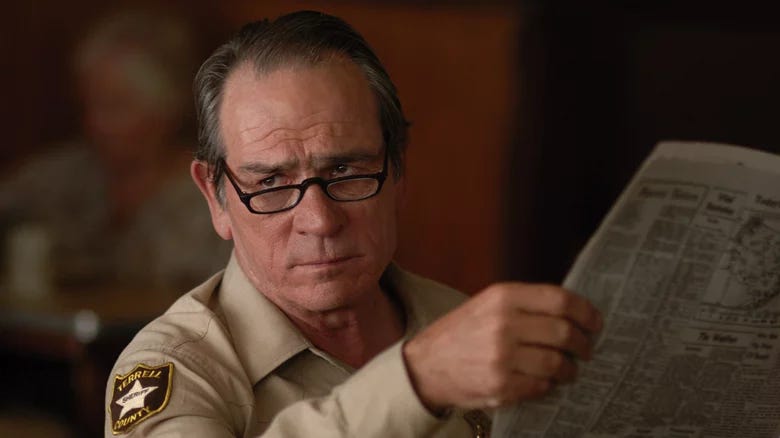

In Cormac McCarthy’s 2005 novel, No Country for Old Men, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, played by Tommy Lee Jones in the Coen brothers’ award-winning film adaptation of the book, memorably sums up the hardened realism of his World War II generation in response to a question about why crime and drugs are so out of control in 1980’s West Texas:

It starts when you begin to overlook bad manners. Any time you quit hearin Sir and Mam the end is pretty much in sight…It reaches into ever strata…You finally get into the sort of breakdown in mercantile ethics that leaves people settin around out in the desert dead in their vehicles and by then it’s just too late.

Although fictional, this folksy wisdom of the older generations about a world devoid of basic morality and ethics is often ridiculed by young people as reactionary sentiment coupled with an unwillingness to change with the times. Yet Sheriff Bell’s somewhat bewildered attitude toward a violent and corrupt world he no longer understands nicely encapsulates a lot about contemporary American life and politics.

Looking at surveys, American society today is divided between a younger generation that tends to see more good than bad in others and an older generation that tends to see more threats from others while desiring greater protections from a fallen culture that lacks basic decency and courtesy.

This optimism-skepticism divide between generations is even more acute in ideological and partisan terms.

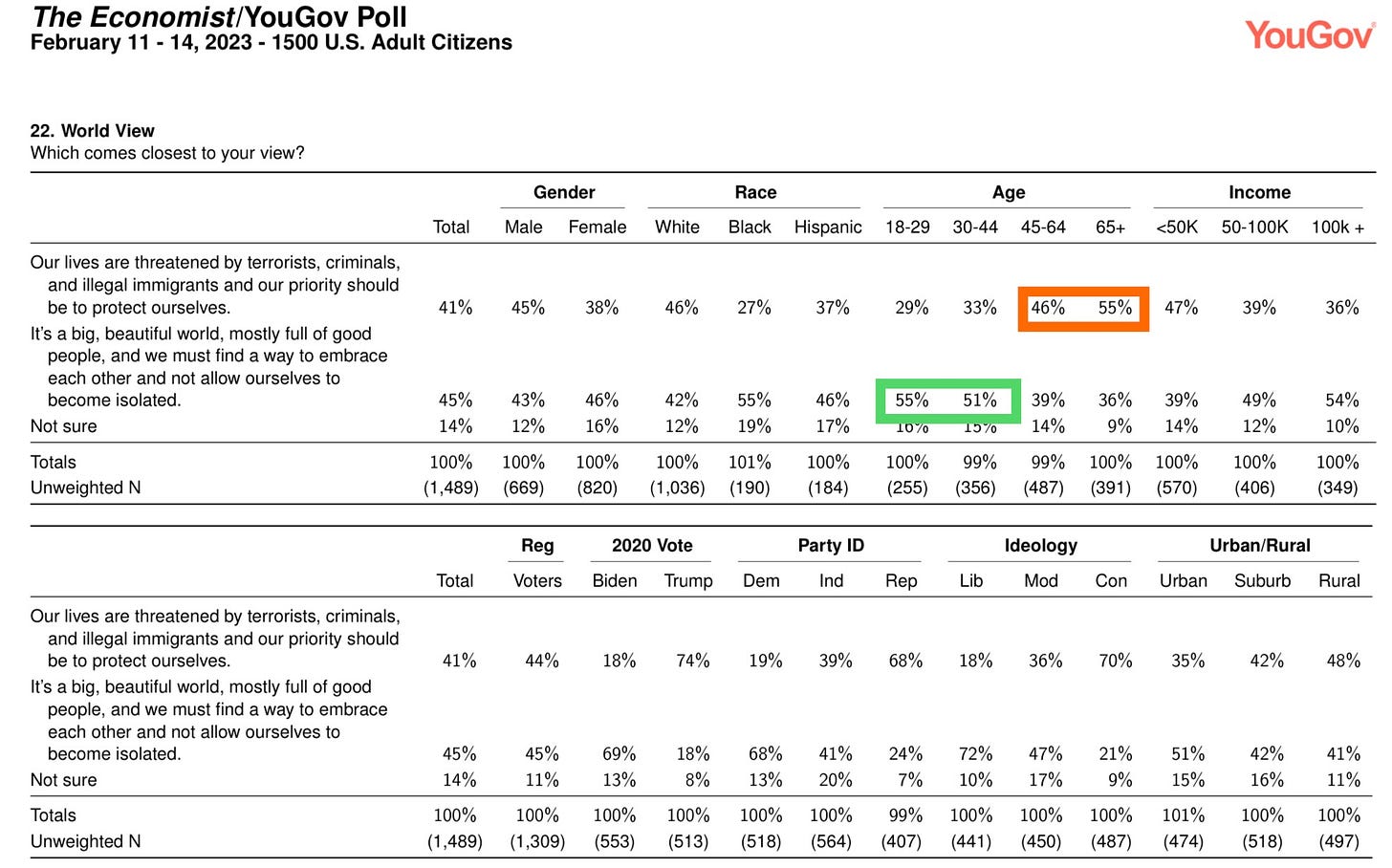

For example, buried in new polling from The Economist and YouGov is a fascinating question assessing Americans’ larger views about the world. The survey asked respondents to select which of two statements comes closest to their own view: (1) “Our lives are threatened by terrorists, criminals, and illegal immigrants and our priority should be to protect ourselves,” or (2) “It’s a big, beautiful world, mostly full of good people, and we must find a way to embrace each other and not allow ourselves to become isolated.”

As seen in the table above, Americans overall are split in their essential views about others: 45 percent of Americans express optimism about the inherent goodness of others and the world compared to 41 percent who express skepticism and desire protection. Another 14 percent of Americans are unsure about how to approach humanity.

Setting aside the limitations of a forced-choice question — it’s not hard to imagine someone responding “I agree with parts of both statements” or “No one talks like that” — the overall split in opinion masks some interesting demographic divides worth considering.

Notably, majorities of Americans ages 18-29 (55 percent) and ages 30-44 (51 percent) agree more with the notion that people are mostly good and that we shouldn’t allow ourselves to become isolated. In contrast, a plurality of those ages 45-64 (46 percent), and a majority of those 65 years or older (55 percent), gravitate towards a more skeptical view of the world. Likewise, pluralities of both lower-income and rural voters view others in a more skeptical light while majorities of higher-income and urban voters hold a more optimistic view of humanity. White people are basically split on the matter, with a slight plurality taking a more skeptical view of others, while a majority of black people and a plurality of Hispanics favor a more optimistic view of others.

The starkest divide in views about humanity emerges along partisan and ideological lines. Consider this: 69 percent of Biden supporters, 68 percent of self-identified Democrats, and 72 percent of ideological liberals believe that the world is full of mostly good people and that we should embrace each other more and try not to be isolated. In contrast, three quarters of Trump voters — and 7 in 10 self-identified Republicans and conservatives, respectively — hold more skeptical views about others and desire greater protection from bad actors.

Interestingly, independents are basically split 40-40 between optimism and skepticism about others, with one fifth unsure — perhaps taking a position more like the Vietnam veteran Llewelyn Moss in McCarthy’s book (played by Josh Brolin in the movie) who just tries to look out for himself and his wife by charting his own way through a confusing and violent world.

What does any of this tell us about modern politics?

Fiction and polls obviously don't explain the world entirely. But they do provide good insights into the complexity of human emotions and thought patterns.

If you want to understand the divide between generations, and the even bigger divide between members of the two parties, it helps to know that there are many people in America, mostly younger and more liberal, who think of others more optimistically and there are other Americans, like Sheriff Bell, who can’t understand what’s happened to society, and his wife Loretta, who won’t read the papers anymore because they are filled with stories of inexplicable violence and depravity.

These basic perspectives about the world in turn structure people’s competing views about crime, immigration, national security, and redistributive social policies.

In general, the more optimistic you are about others, the more willing you are to cut people slack when they mess up and to favor less punitive criminal justice policies and more rehabilitation for offenders. You are also more likely to support higher levels of legal immigration and to think that stopping illegal immigration is less important than meeting the needs of innocent people fleeing economic hardship and political violence. If you hold a generally optimistic view of other people, you probably also favor less spending on weapons and the military, and more spending on anti-poverty and economic support measures for those lacking opportunities.

Conversely, if your worldview is more skeptical about the inherent or potential goodness of others, the more willing you are to favor strict and certain punishment for those who break the law along with greater concern for the victims of violent crime. You are also more likely to favor tight border controls and reduced immigration levels and to take a hard line on illegal immigration. You probably also favor robust defense spending and a strong military, and generally want to see less spending on redistributive measures not aimed at law-abiding, rule-following Americans.

If you find yourself in between these two perspectives, like political independents or Lleweyln Moss, you probably formulate your own path forward in dealing with others and want the government to find a more practical way to deal with people as they are, both good and bad. This third-way path requires a basic openness to people and fair treatment of everyone, coupled with a realism about the world that removes the bad actors from society while expecting others to act lawfully and with basic decency towards others.

This third-way realism may not create the exact country that the good-hearted but world-weary Sheriff Bells of America want to see. But it could create a stronger country that blends the optimism and desires of the young with the realism and experience of the old.

It would seek to create policies that provide both economic and social opportunities for those young people trying to make their way in the world and protections for those of older generations who want to maintain what they’ve built for themselves and the country.

Unlike the fictional world of books and American politics, this third-way path would acknowledge that human nature is not fixed one way or another. There are good people and bad people — and people in between — and the country needs to accept the reality of all of them.