Nobody Likes China

And America Stands to Benefit from Shifts in Global Public Opinion

At the end of June, Pew released a global public opinion survey on attitudes toward China around the world. The poll took the pulse of the public in seventeen nations in Western Europe, North America, and the Western Pacific. Its findings were striking: in virtually every nation surveyed, the public viewed China unfavorably – and strongly so. Only in Greece and Singapore did majorities of 52 percent and 64 percent, respectively, give Beijing a favorable rating.

These negative favorability ratings come even as a number of countries in Western Europe give Beijing generally positive marks for its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Opinions are split in North America, with a majority of Americans saying the Chinese government handled the pandemic poorly while half of Canadians think Beijing handled it well. In the Western Pacific, the public views China’s pandemic response much more negatively: strong majorities of Australians, Taiwanese, South Koreans, and Japanese (as well as a plurality of New Zealanders) see China’s handling of the pandemic as bad.

In addition, all countries save Singapore prefer a close economic relationship with the United States rather than China. With the exception of a single-point plurality among New Zealanders, majorities Taiwan and Japan to France, Italy, and Sweden all prefer to be economically close to the United States.

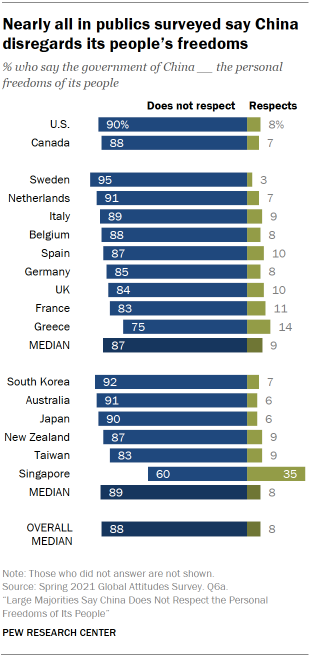

But it’s human rights that appears to drive negative global attitudes toward China. In each of the countries Pew surveyed, “a majority – and in many cases a large majority – agrees that the government of China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people.” Pew analysts performed a simple regression analysis and found a solid correlation between negative general attitudes toward China and the proportion of a population that says Beijing does not respect human rights.

So what does this all mean for the United States?

First, the widespread perception and sordid reality that China’s ruling Communist Party does not respect the freedoms of the Chinese people gives the United States an advantage – at least among the traditional allies surveyed by Pew. Like the United States, these countries tried their best to engage China over the past thirty years, often on the theory that trade and economic engagement would lead to domestic political change in China itself. But that theory didn’t pan out, and China’s geopolitical ambitions and human rights abuses at home – and perhaps its position as the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic – have rapidly accelerated shifts in public opinion against Beijing.

Second, it means that America’s China policy cannot ignore concerns about freedom – either at home or among long-standing American allies. As Pew’s analysts note, Americans brought up concerns about Beijing’s human rights record and political system most often in open-ended questioning. That also means that accommodating Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions, as some alleged realists on the progressive left advocate, ought to be a non-starter – and that concerns about freedom and human rights in China won’t go away if they’re not discussed out of fear such language might lead to a “new Cold War.”

Finally, widespread agreement that China’s government doesn’t respect basic freedoms and a preference for economic ties with the United States don’t necessarily translate into agreements on particular policy approaches. As European attitudes toward Beijing’s pandemic response indicate, geographic distance gives America’s trans-Atlantic allies a little more room for complacency and positive thinking about China than those closer to the diplomatic and geopolitical frontlines. Likewise, New Zealand has refused to cross Beijing – though recently the country’s defense minister warned about the potential for a “storm” akin to China’s dispute with Australia.

All in all, the United States should exercise patience with allies and firmness with Beijing. The Chinese government appears to be going out of its way to alienate other nations, or at least advanced industrial democracies allied with the United States. That means there’s no reason to force, say, New Zealand to make a stark choice about its relations with China and the United States before it’s necessary to do so. Recent comments by Japanese government officials on whether or not Japan will help militarily defend Taiwan, for instance, also show the need for the United States to let its allies come to their own conclusions about China policy.

Similarly, there’s no reason for the United States to accommodate China’s geopolitical and international economic ambitions. Most countries prefer economic ties with the United States, giving the United States an advantage – one that’s already starting to play out when it comes to the semiconductor industry. Ironically, Beijing remains America’s best asset – its reckless attempts to bully and coerce other nations only serve to alienate them and demonstrate the value of ties with the United States.

At home, there’s no reason for either anti-China hysteria or denial. As Pew’s survey shows, Americans do not like the Chinese government and its ruling Communist Party – primarily because it fails to respect basic rights and freedoms at home. China’s power and influence are a concern and a challenge, but ones the United States can handle without losing its mind or sticking its head in the sand.