Should You Trust the News?

This is a surprisingly difficult question to answer objectively.

The News Literacy Project, a nonprofit organization focused on helping “educators teach students how to tell fact from fiction,” recently released a sobering study of young people’s trust and confidence in the news media, following up on a 2024 survey of 1,110 American teens ages 13-18 that showed serious concerns about the accuracy, impartiality, and fairness of journalists and news organizations.

The new research entitled “’Biased,’ ‘Boring,’ and ‘Bad’” employed a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods that reveal highly negative sentiments about the news media among the youngest Americans, including:

An overwhelming majority of teens (84 percent) express a negative sentiment when asked what word best describes news media these days.

When asked to think of one thing they think journalists are doing well, roughly 1 in 3 teens (37 percent) offer negative feedback, saying things such as lying and deceiving (81 responses) or that journalists don’t do anything well (66 responses).

More teens believe professional journalists regularly engage in unethical behaviors than they believe journalists regularly engage in standards-based practices. For example, only 30 percent of teens believe journalists frequently confirm facts before reporting them. In comparison, half of teens (50 percent) believe that journalists frequently make up details, such as quotes, to make stories more interesting or engaging.

When researchers asked these teens what is the one thing that journalists could do to improve their trade, the responses were clear—“Get the facts right and minimize the bias.”

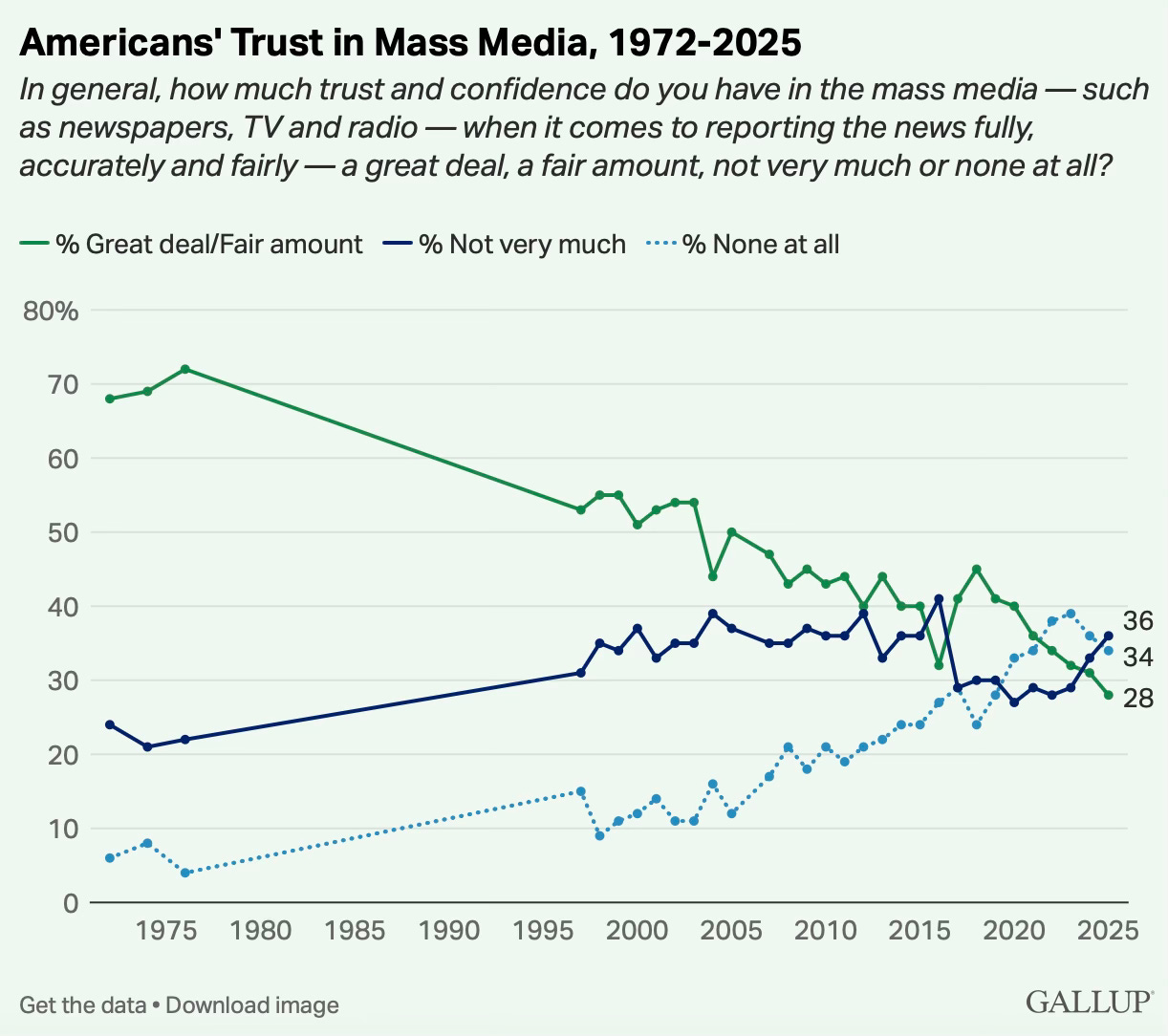

I doubt many grown-ups reading these findings would disagree with the youngsters. In fact, according to recent Gallup research, only 28 percent of U.S. adults today report a “great deal” or “fair amount” of trust and confidence in newspapers, television, and radio to report the news “fully, accurately, and fairly”—down from a recorded high of 72 percent in 1976.

There are clear partisan trends among adults on trust and confidence in the news media that help to explain the decline. A full 62 percent of Republicans today say they have no confidence at all in the accuracy and fairness of mass media, up from only 12 percent of Republicans who felt this way in 2002. In contrast, 51 percent of Democrats today express a great deal or fair amount of trust in the media, down from a high of 76 percent in 2018. Among independents, “trust has not reached the majority level since 2003, and the latest 27 percent reading matches last year’s historical low,” according to Gallup.

Having established that most adults and teenagers do not trust the news, with notable differences based on partisan orientation, the question then becomes, “Should Americans trust the news?” This is surprisingly difficult to answer.

Let’s break down the two main components of this question—”trust” and “news.”

Trusting something or someone basically means that you find an organization or person reliable and truthful. In the context of the media, reliability is established over time based on the repeated experience that a particular media institution (and by extension its journalists, editors, editorial writers, photographers, fact checkers, video producers, etc.) publishes solid information for consumers and fixes any errors or misleading information they might produce due to rapidly unfolding events with uncertain or conflicting accounts. Being truthful simply means that a media organization reports something that in fact happened or that they accurately describe a sequence of events or present a public official’s statement in a correct and neutral manner.

Therefore, you might “trust” a media organization that reliably presents truthful information on a regular basis and “distrust” those that do not. Which media entities fall into which category of trust is a matter of individual taste and experience.

“News,” on the other hand, sounds easy to define but is not. News to most people typically involves straightforward events that occurred, like “A magnitude 6.2 quake struck southeastern Afghanistan just before midnight on August 31” or “U.S. President Donald Trump called Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi this week.”

But events aren’t always that simple.

As the latter example shows, news often involves more than just an event taking place—it includes the credibility of sources, varying accounts of what happened from those with direct or indirect knowledge of it, the wider context of an event, and “behind the news” analysis of how and why the event may have unfolded and what might happen next in the story. Each additional component in this news chain, from an event happening to a report explaining the event appearing in the media, introduces the potential for more reporting errors, bias, or misinterpretation that ultimately undermines consumer trust in a news organization if these mistakes are egregious, purposeful, or uncorrected.

In the case of the Trump and Takaichi discussion, The Wall Street Journal reported that after talking with Chinese leader Xi Jinping about the Japanese PM’s parliamentary comments on how a possible Chinese attack on Taiwan “could mobilize a Tokyo military response,” President Trump advised her “not to provoke Beijing” on the matter and “suggested to Takaichi that she temper the tone of her comments about Taiwan” but not “walk back” her initial statement.

What exactly was going on here? Should you trust the WSJ’s write-up of the event?

The WSJ report was based “on the account of Japanese officials and an American briefed on the call.” No reason to doubt that. The Journal is a reputable paper with exemplary journalistic standards on the hard news side, even with its conservative-leaning editorial board. The call apparently did happen and in the sequence described in the article.

But were the description and substance of the call and the exact advice Trump offered to the Japanese PM correct? Did Trump in fact counsel Takaichi not to provoke China over Taiwan, as the article reports?

Japanese officials later told other media sources that the WSJ was wrong about this and that the president did not tell the prime minister not to provoke China on Taiwan’s sovereignty issues. So which account is real? And if the initial reporting was correct, what was the motivation or purpose of Trump’s counsel? It’s not clear apart from some speculation related to a trade deal with China. And if the reporting was not correct, why did someone anonymously claim that the president did say these things to the Japanese PM, and for what reason?

What is the news, and what is someone’s agenda?

This particular news report covers just one small event in a sea of actions and statements by governments and public officials on all matters domestic, foreign, and economic. Most normal people don’t care much about these matters or have the time and patience to fact-check everything they read, see, or hear.

Americans do know that governments, political parties, and corporations often lie or mislead the public and that the media is all too willing to go along with it uncritically at times. At the same time, they also know that professional activists and ideologues want to convince them that everything they hear from the other side or from a government official or from a corporation is a form of “gaslighting” and propaganda not to be believed.

So, regular citizens protect themselves by establishing patterns in their minds about the trustworthiness of the sources of the facts they hear about in news events (from public officials, corporate spokespersons, political parties, experts, activists, religious leaders, etc.) and the media institutions that report and analyze these events (the mainstream press, cable news, digital sites, social media posters, online influencers, podcasters, etc.).

Right now, as the data above show, the public is assessing these sources and the media outlets that report on them and concluding, “A pox on both your houses. I don’t trust you.”

But with the right approach to the news, it need not be like this indefinitely.

This one diplomatic news example, although seemingly inconsequential, gets to the heart of the matter about why people trust or distrust the news. Unlike in 1976, when trust in mass media was at its highest, American news consumers today rarely get “just the facts” news reporting from a handful of mostly reliable sources. Instead, there is an “event that happened,” like the Trump and Takaichi call, and then a smorgasbord of other media reports and commentaries that seek to describe, explain, analyze, contextualize, rationalize, or criticize the event that happened after the fact.

I would contend that these secondary news accounts are the primary source of much of the public’s rising distrust of the media—especially when they involve hotly contested events with competing facts and interpretations such as the Iraq War, the financial crisis, the 2016-2024 presidential elections, the Covid pandemic, or the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Gaza conflicts.

These major world events obviously occurred. But how and why they happened, who or what is responsible or not responsible for the events, and what should be done about it are all highly debatable subjects.

So, should you trust this type of secondary “beyond the facts” news? It depends.

My advice would be: (1) take in a consistent diet of information from long-standing news organizations that spend considerable resources gathering facts and data and follow strong journalistic standards; (2) carefully scrutinize for accuracy the sources of information presented by these outlets and any studies or data relied upon in their stories; and (3) explore as many competing expert, outsider, partisan, and ideological interpretations of this information as possible (with due skepticism) to triage the news and arrange these secondary sources into a hierarchy of trust and reliability that hopefully will help you make sense of the facts and other complex information about the world.

If parsing the news like this sounds like a lot of work, unfortunately it is. That’s why all the contemporary media outlets are filled with video clips, cultural stories, memes, pictures, recipes, puzzles, shopping tips, advertisements, and celebrity features to distract you. They have to earn your interest, trust, and dollars somehow, and it doesn’t seem to be working with coverage of the news itself.

If there is no political angle in the story, the press will generally get it right. A story about a natural disaster in Asia doesn't have a political angle so they will probably report it straight, although if they can shoehorn in something about climate change, they will.

The media lies mainly by omission and framing. If a story reflects poorly on a Democrat the media will ignore it. Pop quiz: Who broke the Monica Lewinsky story? Answer: Matt Drudge.

The running joke is that if a Republican screws up, the story is about Republicans screwing up. If a Democrat screws up, the story is "Republicans Pounce."

Another tactic is to order stories based on whether they like or dislike the target of a controversy. If a Republican is the target, the story will lead with 5 grafs of inculpatory evidence and maybe a throwaway exculpatory fact at the end. If a Democrat is the target, the put in 5 grafs of exculpatory evidence after the obligatory Republicans Pounce language.

Bottom line: The vast majority of the media is on Team Blue, and that IMO is a function of institutions that pump out journalism majors and not the opinions of the owners. Even the Wall Street Journal is just another also-ran TDS rag these days.

Lately a lot of bias in news is up to the individual writer more than the source publishing them.

The Taiwan/Tokyo/Trump story is a good one to use as an example. The WSJ account reads like what a foreign service professional would coach Trump to say. Responsible, not provoking, supportive of our ally, and exactly what the Japanese PM is doing anyway. Might well of been what was said. Also there is the filter of being translated into two very different languages.

Facts everyone could probably agree with are that Trump and Takaichi met and discussed Taiwan without any visible fireworks or difference of opinion. China wasn't overjoyed.

Ad Fontes the media rating website gives the WSJ fairly good ratings, I should subscribe instead of the NYT which tends to cause my blood pressure to rise with regularity. I wish there were a place to go to get unbiased news. Some places give both left and right but that's not the same as lack of bias. Most mainstream news does tend to get left of center ratings, and writers themselves even further left. There are people who track word choice across all media, and the entire industry is left coded.

Maybe part of the problem is that "just the facts" can be stated in a short three paragraphs, but people want content, so a story gets stretched out to 35 paragraphs with plenty to piss you off. I might be a lefty but I really want to hear a neutral telling, appealing to my left bias mostly just makes me suspicious.