The Political Reality Facing Center-Left Parties Globally

Voters across the world are anxious about quality of life, crime, and housing issues. Values-based and pragmatic policies can provide a path forward.

To craft effective political strategies that can attract voters and win elections, social democratic, labor, and liberal parties must first understand voters’ hopes and dreams for themselves—as well as their fears and anxieties about the future. Comprehensive new polling conducted in 20 countries on 4 continents with 22,000 total respondents, designed by Global Progress and YouGov ahead of the G20 summit in Rome, provides a wealth of important data about these hopes and fears and explores how voters view an array of cultural, economic, and political challenges in their respective countries.

As with earlier research around economic recovery issues post-pandemic conducted before the G7 summit in Cornwall in June, TLP was fortunate to work on this 20-nation project led by Matt Browne, Hans Anker, Alex Schmitt, Sophie Brown-Heidenreich, and Jon Will Chambers of Global Progress and Marcus Roberts and Lydia Pauly of YouGov.

The biggest takeaway for center-left party strategists and leaders? Voters worldwide are deeply pessimistic about the future and seriously distrust politicians. This pessimism cannot be ignored. But voters are open to values-based, pragmatic, and patriotic agendas that are carried out well and centered on enhancing the quality of life for all people.

Some of the more interesting findings from the 20-nation poll include:

Voters in most countries are wary of change and express serious doubts about political leadership. The survey asked respondents in all 20 countries to indicate whether “on balance when things change it normally means things” get better or get worse for most people. In all but 3 countries—Indonesia, Mexico, and India—less than half of voters feel that change usually means things get better for people. The pessimism is particularly pronounced in leading industrialized nations such as the United Kingdom (15 percent), France (21 percent), Italy (23 percent), the United States (24 percent), and Germany (29 percent) where less than 3 in 10 citizens said change normally means things get better for most people.

On top of this general skepticism about change, voters across all 20 nations take a dim view of the motivations and outputs of the political leaders running their respective countries. Roughly two-thirds of people surveyed in aggregate disagree with statements that politicians are “realistic about their ability to deliver on their plans” (69 percent disagree), “honest about their reasons for their plans” (69 percent disagree), and “understand what their plans mean” for people like them (65 percent disagree).

Combined, these data suggest that political parties and leaders in most countries need to adjust their aperture to get a clearer picture of voters’ background concerns about change overall, and better understand their skepticism about politicians’ intentions and capabilities in dealing with change in the future.

Voters globally are particularly concerned about quality of life, crime, and housing issues over the next ten years. Diving into more specific issue areas, the survey asked respondents in all 20 countries to indicate whether they think things will get better or worse in the next ten years on a range of social and economic issues.

As seen in the summary chart above, more than half of people across all 20 countries feel that “crime” and “economic inequality” will get worse in the next 10 years, with more than 4 in 10 feeling similarly about “housing”, “economic prosperity”, and the “quality of life”. Looking at the country breakdowns below, concerns about these top issues are more pronounced in countries like France, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and the Netherlands along with Brazil and South Africa.

Why does this matter? First, as seen below, issues such as quality of life, crime, and housing emerge as top tier concerns for voters across all 20 countries (along with health care which is generally seen not to be as bad in the future as other issues). In a follow up question asking people which of all these issues is the single most important priority for them, quality of life emerges on top chosen by more than one quarter of respondents across all 20 countries.

Second, party strategists and candidates need to recognize that if people say issues like crime, quality of life, and housing are top priorities for them—while also feeling that these same issues are going to get worse in next decade—they are facing a huge political problem if their parties and campaigns are not also focused on these core concerns of voters.

Political parties will thus need to devise strong measures to address these top quality of life concerns and shape existing policies to better fit voters’ desires. If not, they risk being seen as wildly out of touch with the voters they seek to represent.

People favor carrots over sticks on climate change. As world leaders gather in Glasgow for the COP26 negotiations on climate change, it is critical to remember that most voters in most nations favor pragmatic steps to ease the transition to cleaner energy over more punitive ones to tax carbon emissions.

As seen on the right in the chart below, when presented with a choice of approaches on dealing with climate change, majorities of voters across all 20 countries clearly prefer steps to “provide subsidies and incentives to business and consumers to make it cheaper and easier to provide and use environmentally friendly goods and services” (55 percent) over alternative steps to “tax carbon so those industries and consumers who pollute the environment most are forced to pay for this” (33 percent).

As seen in the middle of the above chart, in terms of who is most responsible for dealing with climate change, people overwhelmingly believe it is first the responsibility of governments to tackle climate change followed by businesses with “individual people like me” a distant third.

Combined, these data suggest that climate action needs to be highly pragmatic and focused on jobs and clean energy industrial policies led by governments, subsidies to help offset energy transition pain for citizens, and generally more investment carrots over behavioral sticks to get political support.

On immigration, citizens want clear rules and enforced borders along with steps to better integrate immigrants into local communities. More than 40 percent of people in 16 of the 20 countries examined in this survey believe that the number of immigrants coming into their respective nations is “too high.” But as seen in the chart below (showing mean averages for various ideas with ‘1’ being very important and ‘5’ being not important at all), strict limitation on the number of immigrants is a less appealing policy to voters than other ideas like “making sure there are clear, consistently applied rules about who can come” to their country along with “enforcing the borders.”

In another question, voters across most countries believe that steps like immigrants “adhering to the rules in our country” and “learning to speak our language” are critical measures to help improve integration.

The results on immigration are obvious: parties that want to lead governments must be seen as providing and enforcing clear rules about who can enter their countries and why, while ensuring that immigrants who do move to their countries adhere to national rules and norms, learn the national language, and take better steps to integrate into local communities.

People across the world are skeptical about the near-term impacts of artificial intelligence and technology on jobs and incomes. The technology impact results in this survey should serve as a wake-up call to party leaders across all nations.

As seen below, citizens on balance do not believe these emerging technologies will be good for jobs, earnings, or equality. By a 22-point margin, people across all 20 countries believe that the impact of artificial intelligence and other technological innovations on “the availability of jobs” will be negative not positive going forward. By a 9-point margin, people feel similarly about the negative versus positive impact of technology on “the amount of money people earn.”

In contrast, people feel more positive than negative about the impact of technology on “future generations” generally and on “people’s work-life balance.”

Housing affordability is quickly becoming a top tier concern for people in most countries. The ability of people to find and afford housing continues to weigh heavily on the minds of voters in all parts of the world.

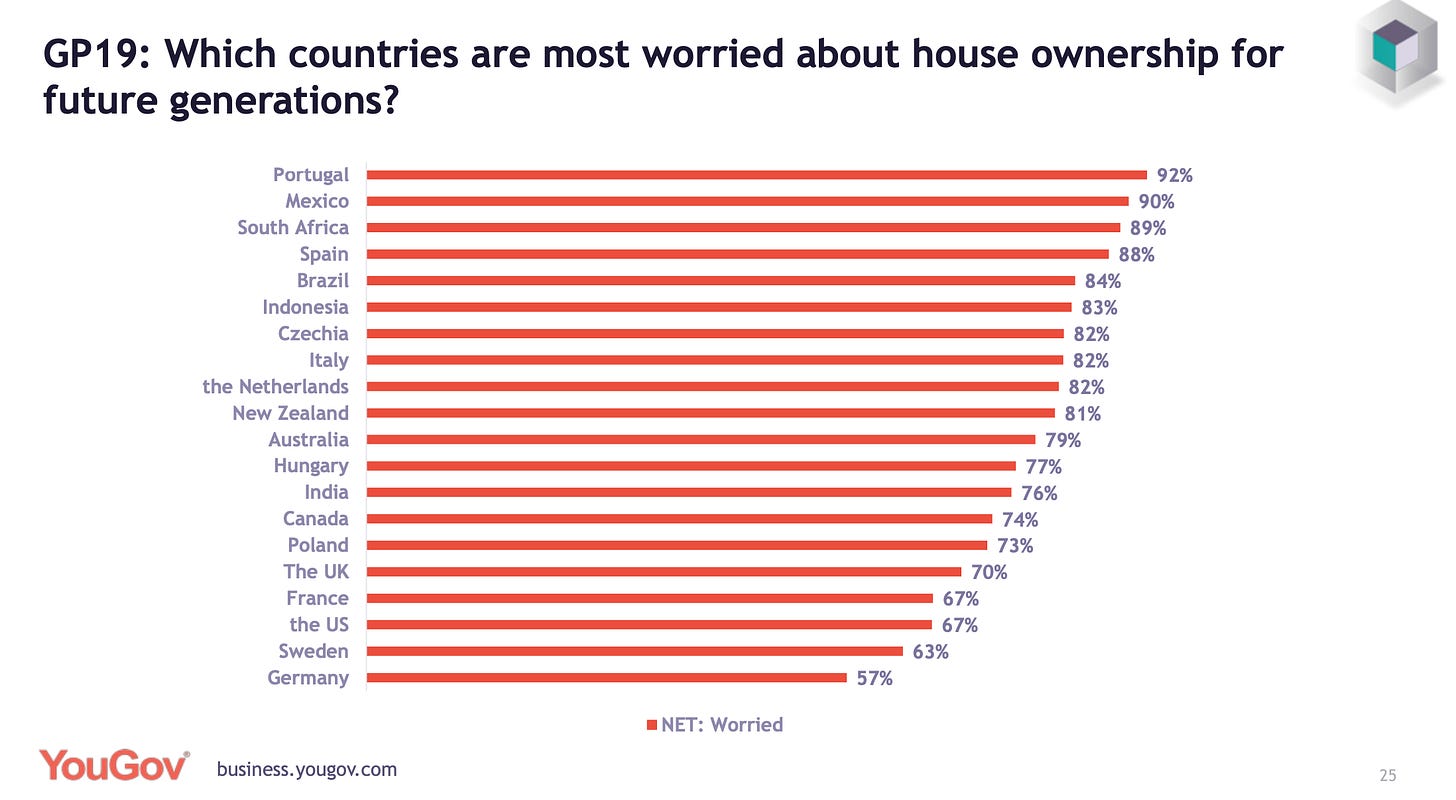

As seen in the chart below, approximately 6 in 10 to more than 9 in 10 people across all 20 countries express worries about home ownership opportunities for future generations. Concerns about housing are most elevated in countries like Portugal, Mexico, Spain, Brazil, Italy, and New Zealand with concerns slightly lower but still high in places like France, the UK, the US, and Canada.

In terms of solutions, citizens in most countries want their governments and localities to focus on building more affordable houses, fighting speculation, and ensuring good interest rates for borrowers.

Citizens across nations back a range of practical solutions to various social and economic problems. Fortunately for progressive forces globally, there are several pragmatic policy steps that can be taken by parties and leaders to help address people’s concerns about quality of life and economic issues.

The survey presented respondents with a list of specific policy ideas and asked people whether they think each one is a good proposal or a bad proposal. As seen in the chart above, voters across all 20 countries overwhelmingly view each of these ideas as good proposals for their respective countries, with support ranging from 58 percent to 78 percent in total. At the top of the list of good proposal ideas is “national housing policy” followed closely by Nordic-style “city and countryside” initiatives and “skills accounts” for workers.

The United States stands out as an outlier on these proposals, with slightly lower overall support emerging due to sharp party polarization between Democrats and Republicans.

Remember, most people in most countries still occupy the ideological center—not the left or the right. Looking at ideological self-identification across all 20 countries, the survey finds more than 40 percent of people in aggregate placing themselves in the center on both cultural and economic issues, with less than one fifth placing themselves on either the left or right on both fronts, respectively.

It remains a basic reality in politics, borne out across multiple national contexts in this survey, that leaders who capture the center are more likely to prosper than those who do not.

There are many more rich questions and findings in this research project that will be presented in a later report.

For now, political parties and leaders should take to heart what voters in this survey are telling them about their priorities. They should tailor party ideas, policies, and messages to meet voters where they are through values-based, pragmatic, and patriotic steps to improve national economies and the quality of life for all people (including on jobs, crime, housing, and health care issues).

Parties of the center-left can be successful in future elections and in government by putting forth pro-worker and pro-family policies that offer voters clear and achievable ideas for improving their everyday lives wrapped in patriotic national values, rather than radical plans wrapped in esoteric language that seem out of touch and unrealistic.