The Way Forward on China

Why neither belligerent confrontation nor appeasement will secure America's global interests or advance liberal values in China.

Editor’s note: This perspective on America’s China policy comes from a senior China analyst at a large global organization who wishes to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of their work and position.

The United States has been both hated and loved in China.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the United States was part of the “Eight-Nation Alliance” that invaded and humiliated the Qings, China’s last dynasty; that defeat is bitterly remembered as the beginning of China’s “century of humiliation” as its ancient civilization fell behind what it considered to be culturally inferior West. But the U.S. also supported the founding of modern China after the Qings, and some leading Chinese modernizers like Sun Yat-sen looked to America as a model of democracy. However, this U.S.-backed Nationalist government lost its civil war against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—long hostile to the U.S. and democracy—which then established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. The Nationalists fled to Taiwan. For decades, the United States did not diplomatically recognize the PRC.

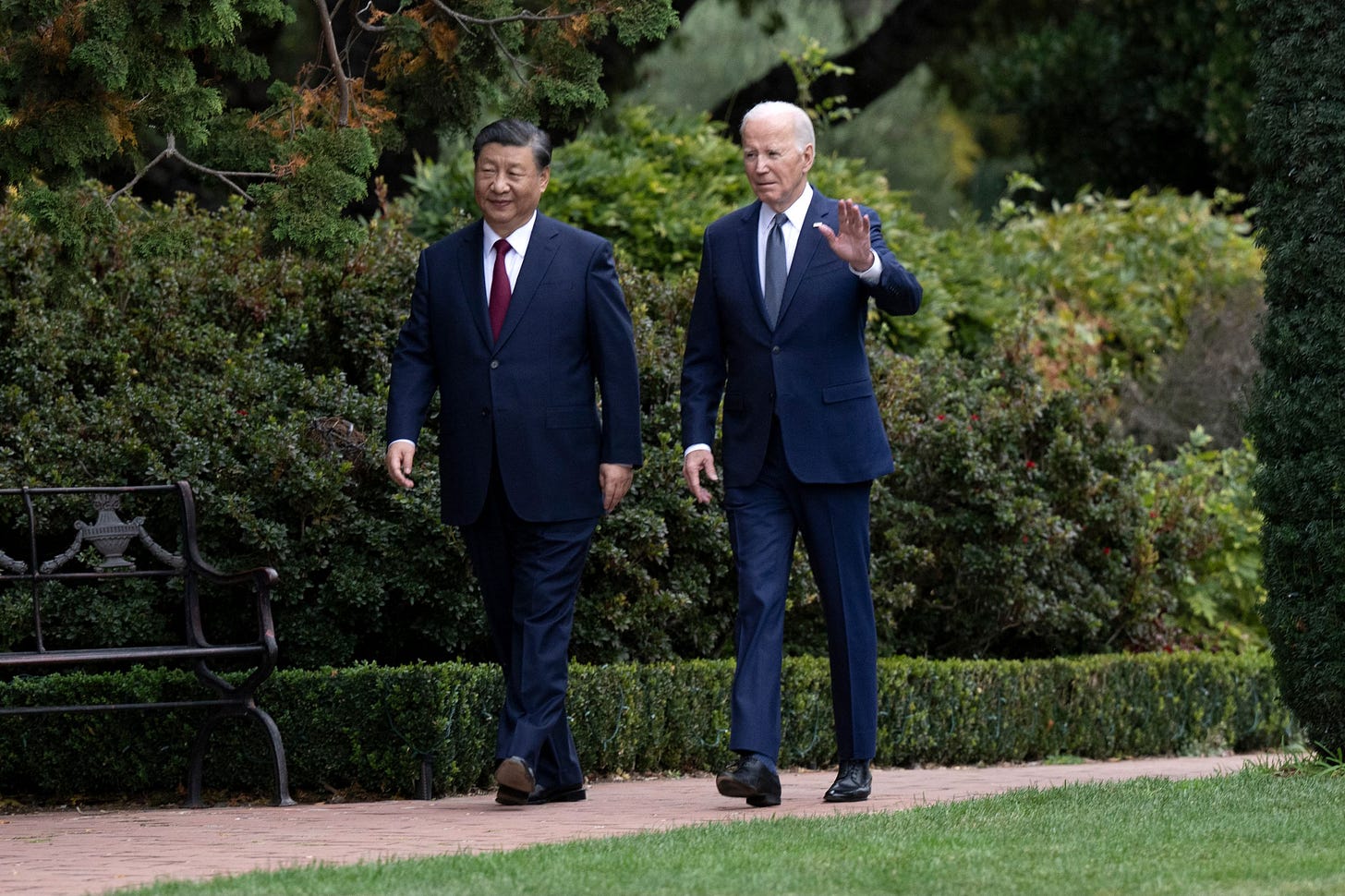

But as the PRC soured on the Soviet Union, U.S.-China relations warmed. President Richard Nixon visited China in 1972, and President Jimmy Carter normalized relations with China in 1979. Carter recognized the PRC as the sole legitimate government of China and adopted the “One China” principle. America stopped recognizing Taiwan’s government, but the U.S. Congress also passed the Taiwan Relations Act to maintain cultural and commercial relationships with Taiwan. Importantly, that act also requires that the United States supply the island with defensive arms.

Relations between the U.S. and China went into a deep freeze in 1989, after the Chinese government’s massacre of pro-democracy protesters at Tiananmen Square. But in 1993, President Bill Clinton, who had strongly criticized Beijing on the campaign trail the previous year, launched a policy of “constructive engagement” with the Chinese government, paving the way for it to join the World Trade Organization in 2001. Clinton and other American advocates of constructive engagement claimed that bringing China into the global economy would eventually and inevitably liberalize the country’s politics.

After joining the WTO, the PRC’s economy skyrocketed. The Chinese government also stood accused of adopting policies that unfairly furthered its advantages, such as keeping yuan’s exchange rate at artificially low levels and thus its exports cheap and competitive. More importantly, Chinese industries viewed as strategic by the CCP—particularly advanced technologies, including clean energy—received subsidies and benefited from forced technological transfers and theft in the hope that they would overtake and edge out similar industries in the West.

Parts of the U.S. government increasingly realized the problems involved in China’s rise, but as a whole Washington did little to address them. The two economies became heavily intertwined: U.S. multinational corporations lobbied against actions that might have jeopardized their profits, while the United States did not want to wean itself from cheap goods or plentiful capital from China. The Chinese government cultivated American elites on both sides of the aisle, particularly those in the business world, as part of its “United Front” strategy, coopting them to promote—or at least not oppose—the Chinese Communist Party’s views. As a result, there was little to no effective action to address growing Chinese government behaviors by U.S. administrations from Clinton to Obama.1 Along with the Chinese government intimidating and marginalizing voices critical of it in the United States itself, American policies towards China remained largely harmless and cost-free to the CCP.

Over time, the PRC became the world’s second biggest economy and America’s biggest creditor. Since the 2008 global financial crisis—and especially after Xi Jinping came to power in 2013, and then again following Trump’s election in 2017—China has become increasingly assertive and abusive both at home and abroad. Trump’s administration capitalized on the growing alarm and resentment towards China in the U.S. and shifted the American—and America’s allies’—orientation towards China from “engagement” to “competition.” His administration imposed tariffs on Chinese goods in 2018, for instance, many of which have been retained by the Biden administration.

Today, U.S.-China relations are increasingly defined by competition that some in the U.S. describe as “existential” and others criticize as “zero sum.”2 They are competing on all fronts—political, economic, technological and military. The two remain economically intertwined, and the extent to which they can “de-risk” or decouple from each other is not yet clear.3 The U.S. and China are reverting to Cold War dynamics, cultivating allies to counter the other. China has moved closer to Russia and also Iran. The European Union, long a U.S. ally and comprised of many NATO member nations, remains caught in the middle: it is economically reliant on China to a greater degree than the U.S., and it has grown concerned with growing China-Russia ties. And yet many EU leaders wish to maintain some sort of independence from the U.S., and remain wary of a second Trump presidency or yet another Trump-like president.

As China rises in importance in US foreign policy, the number of people involved in China policies and the amount of China-related legislation increases. But overall, America’s China expertise remains limited and piecemeal. Few policy professionals in the government are fluent in Chinese, and even fewer can accurately read the Chinese Communist Party’s policies and practices—especially given that CCP policy processes are black boxes, particularly so under Xi. Moreover, many of those with China expertise were part of the engagement era and remain unwilling to shift towards a more critical approach. For some, their experience with China primarily meant doing business with the CCP. For academics and think tankers, a need to maintain access to China often means they keep topics and people the Chinese government dislikes at arm’s length. Other influential voices are China’s elites, who promote the Chinese Communist Party’s views. While human rights organizations have played an outsized role in U.S.-China relations, bringing marginalized voices of people from Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, and China proper to the table, U.S.-China relations remain determined by elites from both sides.

Major policy choices on the left and the right

Broadly speaking, the U.S. has adopted two opposite orientations towards China since re-establishing ties with Beijing in 1972: “engagement” and “competition.” Engagement, a bipartisan consensus for about 40 years, has fallen largely out of favor.4 Competition is now largely the bipartisan consensus across both the Trump and Biden administrations, though its precise content, emphasis, and policies varies.

The Trump administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy first laid out China alongside Russia as existential threats that “challenge American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity.” Both Moscow and Beijing, the strategy said, “want to shape a world antithetical to U.S. values and interests.” Likewise, the Trump administration’s 2020 U.S. Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China determined China to be a “strategic competitor” and said the U.S. now had “a tolerance of greater bilateral friction.” The American “approach is not premised on determining a particular end state for China,” but to “improve the resiliency... [of U.S.] institutions, alliances, and partnerships” and “to compel Beijing to cease or reduce actions harmful to the United States’...national interests.” The document further outlined granular policies spanning across domains, such as “[d]irecting resources to identify and prosecute trade secrets theft, hacking, and economic espionage,” “[r]equiring Chinese diplomats to notify the United States Government before meeting with state and local government officials and academic institutions,” and “[s]trengthen the United States economy and promote economic sectors of the future, such as 5G technology, through tax reforms and a robust deregulatory agenda.”

Another significant China policy document produced during the Trump administration was a 2020 report prepared by the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff that unambiguously described the CCP’s ambitions as nothing less than subversion of the existing world order. It also analyzed the CCP’s intentions and worldviews, describing how they shaped behaviors while presenting ten broad principles for the U.S. to build its strengths vis-à-vis China.

Actual Trump administration policies, however, on China were contradictory, overly broad, departed wildly from stated policies—to say nothing of the numerous liabilities that arose from his America First isolationist approach that alienated with critical U.S. allies to his endorsement of the mass detention of Uyghurs.5

In January 2021, the Atlantic Council published a “Longer Telegram” on China policy. Written by an anonymous “former senior government official... on China,” it asserts that the U.S. only has “a declaration of doctrinal attitude, not a comprehensive strategy to be operationalized” on China. In part, the author blames this lack of strategy on the U.S. having unclear and varying objectives for China, ranging from “inducing economic reform through a limited trade war to full-blown regime change.” It asserts that the U.S. would need “a qualitatively different and more granular policy response to China than the blunt instrument of ‘containment with Chinese characteristics’ and a dream of CCP collapse.” The report then outlines ten actions for the U.S., pronounces priorities and declares interests rather than specific actions which it says should be developed closed-door. The “Longer Telegram” received widespread attention and debate in Washington, especially over its assertion that U.S. strategy on China should focus on exploiting perceived political fault lines between Xi and his inner circle.

For its part, the Biden administration’s China policy has focused on building coalitions internationally and rebuilding America’s strength domestically. In a March 2021 speech, Secretary of State Antony Blinken stated U.S. policy toward China will be “competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be, and adversarial when it must be.” In May 2022, Blinken gave another speech that outlined the Biden administration’s China strategy. The U.S. does not “seek to block China from its role as a major power,” he said, but it “will shape the strategic environment around Beijing to advance our vision for an open, inclusive international system.” He summed up the Biden administration’s strategy towards China up as “invest, align, compete.” Invest in America’s democracy, infrastructure, and innovation; align with its allies built on shared interests like human rights. As to compete, the U.S. seeks to outcompete China in technology and innovation while pushing back against “unfair technology and economic practices,” but the United States “does not want to sever China’s economy from ours.” On the military front, Blinken stated the United States will “hold China as its pacing challenge, to ensure that our military stays ahead” and that it would “continue to uphold our commitments under the Taiwan Relations Act to assist Taiwan” and “resist any... forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security or the social or economic system, of Taiwan.” Blinken emphasized that America would work with Beijing where their interests aligned, including on climate change.

This new bipartisan consensus on China appears to consist of several elements: building America’s strength at home, addressing the Chinese government’s influence in the United States, pushing back against the Chinese government’s economic coercion and forced technological transfer, keeping the U.S. military and technological innovations strong, and advancing or preserving America’s global influence.6

The left and right differ on their focus, however. The right tends to focus on “elite capture,” or the way the CCP influences American politics through its United Front, casting Democrats as corrupt and beholden to Beijing;7 they also tend to push for greater “decoupling” from China. The far right’s talking points and policies often conflate the CCP with people of Chinese descent and, troublingly, frequently promote discrimination and racism.

Some on the left and the center remain proponents of engagement, though many appear to argue for a toned-down version of continued academic exchanges, climate cooperation, and dialogues with the Chinese government. Others on the left advocate shoving human rights aside for the sake of climate cooperation, and they are concerned that any competition framework fosters “anti-Asian hate” and promotes a disastrous “New Cold War.”8 Those even further left think the U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East and Latin America has been so disastrous that it should maintain an overall position of “restraint” in general.

What’s the right approach to China?

There’s no doubt that the Chinese Communist Party has long been a threat to the people in China, home to a fifth of humanity, or that the CCP’s system is the antithesis of democracy, or that its global ambitions already make it a formidable competitor to the United States. The Chinese government has a growing and negative global footprint: it spreads broadly illiberal ideas and technocratic governance solutions overseas that do away with a free press, civil society, and elections. Its Belt and Road Initiative gives out loans that lack transparency and exacerbates corruption; its transnational surveillance, repression, and influence campaigns crush dissent and disagreement; its military build-up and nuclear capabilities paired with an aggressive posture threatens its neighbors; Beijing constantly undermines international human rights mechanisms—the list goes on and on.

But the United States remains globally dominant and leads China by a significant margin across multiple domains. If China overtakes the US as a global power, however, its impact will certainly be far worse than it is even today; democracy may well become obsolete.

The major question now is whether or not a CCP-ruled China ever overtake the United States in terms of global power. Half this question involves whether the CCP even intends to do so, but my opinion is that the Chinese government has long sought to supplant the United States.9 The other half of this question is whether it can do so. My own limited vantage point—primarily examining Chinese society and governance—suggests that the Chinese Communist Party’s power may grow more slowly, along with its economy, than many once expected. Part of the reason is geopolitical: advanced economies have become much more critical towards China and have made it harder for the Beijing to exploit them for growth. China also faces major domestic headwinds, including an aging population, undereducated and undernourished youth in rural areas, and an intellectually stifling and a socially stagnant society where young people no longer feel confident or aim for upward mobility—they would rather “lie flat.” As long as the CCP remains in power, these problems cannot be easily resolved, and some even argue that the Chinese government maybe “peaking.”

China will nonetheless exert a strong negative gravitational pull for decades. But unless it experiences something like a technological quantum leap—always a possibility even though Xi’s China stifles innovation—its ambitions will remain unfulfilled. The other possibility would be if the United States loses or gives up on its democracy in the coming decades, which also remains frighteningly possible.

In the meantime, it is reasonable to expect that the United States will maintain a solid lead over China with room to maneuver. It also follows that its current competition with China on all fronts could, given limited resources and competing priorities, risk overstretching the United States with misplaced priorities that paradoxically may undermine America’s national interests. A more selective or limited competitive policy would be more reasonable given this is a multi-decade marathon, not a sprint. Besides, an overt U.S. drive to maximize dominance across domains already comes off as self-interested globally, irks European allies, risks alienating countries from Brazil to Indonesia.

Accordingly, America should continue to invest at home, especially in health care, education, clean energy, and technological innovation. Some of China’s weaknesses involve an undereducated and undernourished rural population, and similar issues face the United States. Policy fixes like free early childhood education and eliminating child poverty and obesity have become national security issues.

America’s China policy should put a greater emphasis on defending the United States itself, which involves making sure the United States remains democratic and free from Chinese government influence. Some of the policies in the 2020 US Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China seem reasonable, and they should be revisited given that they were released late in the increasingly chaotic Trump administration.

These policies should ensure that:

People in the United States are free to express their opinions about the Chinese government, in part by ensuring that U.S. intelligence and law enforcement officials are equipped with the language skills to investigate China’s transnational repression, and by protecting academic freedom against undue Chinese government influence.

The U.S. political system at the national, state, and local levels are free from foreign interference, by targeting United Front operations and increasing transparency and oversight over foreign political and academic donations.

The U.S. develops its own China expertise, free from Chinese government influence. It should provide alternative funding and educational resources from K-to-12 in Chinese language learning that is not provided by the Chinese government-controlled Confucius Institutes, as well as funding and careers in China Studies free from the Chinese government’s manipulation and influence.

Language skills are not enough: U.S. government agencies should tap into the communities of expatriate and exiled Chinese critics, many of whom are perceptive analysts of the Chinese Communist Party. These critics know how the CCP functions in actual practice, and how it obfuscates its intentions and hides its actions. This kind of frontline know-how will be especially important as fewer and fewer Americans go study in China due to U.S.-China tensions.

Some additional efforts to frustrate and compete with the Chinese government would also be justifiable, but they should not become a blank check that could lead to wasted energy or include those that, in the long term, could prove harmful to US national security—a destructive arms race, for example, or an uncritical embrace of dictators in the Asia-Pacific because they are not on China’s side.

When it comes to the U.S. defense budget, the Biden administration reasonably considers the Chinese military as the Defense Department’s “pacing challenge.” But that shouldn’t be an excuse for unrestrained defense spending or a free rein to develop potentially dangerous weapons systems like, say, artificial intelligence-powered systems.

Technology is another reasonable arena for competition. There’s good cause to stop the Chinese government from forcing technological transfers; recent efforts to control semiconductor exports seem valid. The U.S. should try to attract STEM talent globally by facilitating high-skill immigration as well. It would also mean that the U.S. government should take reasonable precautions to ensure that sensitive technologies do not get brought back to China.

Some U.S. tech giants argue that regulations will harm their competitiveness; this is an example of a bad blank check—the notion that anything should be permissible as long as one is competing against China. On the contrary, U.S. technology companies are stronger when they institute basic safeguards that protect privacy, prevent misinformation, and protect vulnerable people. Recent discussions about artificial intelligence, for instance, have distracted from more readily available methods of protecting privacy—to say nothing of the threat personal data leaks pose to America’s national security.

When it comes to the future of economic relations with China, there are drawbacks. On the one hand, it was a big misstep for the United States and Europe to make themselves so economically dependent on China. On the other, full decoupling also seems unrealistic. Some level of “de-risking”— shielding certain critical supply chains from China—is reasonable. As supply chains move away from China, moreover, the United States should ensure that future transnational trade deals come with stronger workers’ rights protections that have real and effective enforcement mechanisms.

On climate, the United States should not engage with China unconditionally. The terms and benchmarks of such engagement matters a great deal. Given China’s attitudes toward engagement on climate, a competitive approach to address climate change may well work better and should be developed further.

Finally, the U.S. needs to focus on working with others to promote a more secure and stable world. It should seriously and consistently promote human rights globally, not just pay them lip service or treating them as a form of propaganda. Unfortunately, U.S. actions over the years have helped to severely damage respect for international norms; many governments now treat them with contempt or use America’s failings to justify their own even worse behavior. The United States could rectify this situation by signing up to international agreements and treaties, including the International Criminal Court.

See America Second by Isaac Stone Fish for more detail.

Some argue that the CCP has long determined to displace the United States on the global stage, while others assert that the CCP is merely trying to make the international environment safer for its authoritarianism.

There is a vast debate about whether the two economies are indeed decoupling.

Some continue to argue that it was the right strategy at the time, or that it was just not given enough time. See Joseph S. Nye, “The Evolution of America's China Strategy,” November 2, 2022.

For example, the US suspended entry for graduate and postgraduate students and researchers from China in May 2020, departing significantly from his own administration’s stated policies of delineating the Chinese government from the Chinese people. See Nicole Gaouette and Maegan Vazquez, “Trump announces unprecedented action against China,” CNN, May 29, 2020.

The brevity of this briefing paper does not allow include other strategies outside of the Trump and Biden administrations, including those of Melanie Hart, Rush Doshi, and Ryan Haas, which vary in terms of specific ideas but generally involve a mix of building American strengths at home and building American order abroad with allies while frustrating those of China’s across domains.

But the Chinese government has played both sides. See Marc A. Thiessen, “Vivek Ramaswamy has a China problem — and a Hunter Biden problem,” Washington Post, September 26, 2023 and Andrew Solender, “Report: Trump received at least $7.8M in foreign payments during presidency,” Axios, January 5, 2024.

The Center for American Progress, Tobita Chow, and Bernie Sanders exemplify this position.

The debate is whether it intends to supplant the United States, or merely aims to be respected and make the world a safer place for authoritarianism. Rush Doshi, for example, argues in his book The Long Game that the Chinese government’s long game is to surpass the United States.