Think Spatially, Not Racially

Race-based policies are constitutionally dubious and politically counterproductive. Place-based policies work better in creating lasting support for equality and opportunity for all.

America’s infamous political tribalism precludes common action on multiple policy fronts. Democrats think one way, Republicans another—and the twain shall never meet. Caught in the middle are millions of struggling workers and their families who desperately need a hand up but end up as political waste in a never-ending war over competing ideological frameworks and arcane terminology that blocks collective action to assist those most in need.

It doesn’t help matters when political parties present their ideas in ways scripted to generate confusion and sectarian divisions. One major example of this is the often well-intended but politically flawed race-based policy approach favored by the contemporary left and Democrats as a catch-all explanation and solution to America’s economic problems.

The flaws in this approach are obvious: (1) race-based policies are almost always unconstitutional—the government can’t set out to help one group or hurt another based on their race, sex, religion, or national origin; and (2) race-based policies are disastrous politically driving wedges between different groups of working-class people that inhibit majority action on important economic changes and fuel backlash politics that leave everyone worse off.

Yet, much of the policy and political work conducted in the progressive movement today refuses to confront or even acknowledge these limitations. It’s too bad because many smart and committed people within this same network of analysts, activists, and political leaders pursued an excellent alternative approach just a few short years ago: place-based policy analysis.

What is place-based policy?

The basic insight in place-based policy work is that where a person lives and grows up matters as much as their family stability and income level in determining life outcomes. The places that are thriving in America today have common attributes: lots of good paying jobs, effective schools and colleges, top-notch infrastructure, green spaces, safe streets and neighborhoods, and other cultural amenities. The places that are doing less well, or are outright distressed economically, often lack one or more so-called “anchor institutions”—private companies, colleges and universities, hospitals, military bases, or government agencies, etc.—that provide good jobs and positive spillover effects for all people who live there, and particularly for those starting out with fewer economic opportunities.

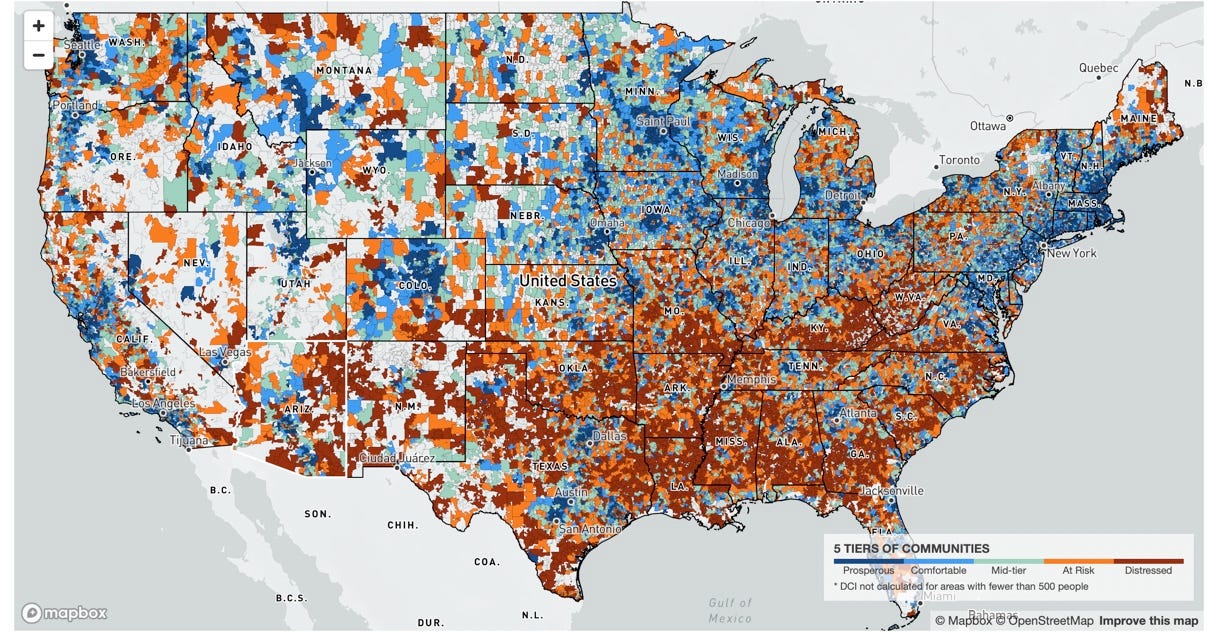

Look at this excellent map from the Economic Innovation Group (EIG). The map shows national zip code-level data aggregated around 7 different indicators—educational attainment, housing, unemployment, income, poverty, and change in employment and private businesses. Places in red and orange are classified as ‘distressed’ and ‘at risk’, while places in dark and light blue are classified as ‘prosperous’ and ‘comfortable’ with those in green being ‘mid-tier’.

What’s notable looking at the big picture is that every state in the country includes a mix of communities classified as either distressed and at-risk or prosperous and comfortable. Some states and regions are doing relatively well, such as those in the corridor along the Eastern Seaboard, while others show much bigger pockets of distress including many communities across the more rural South and Southwest.

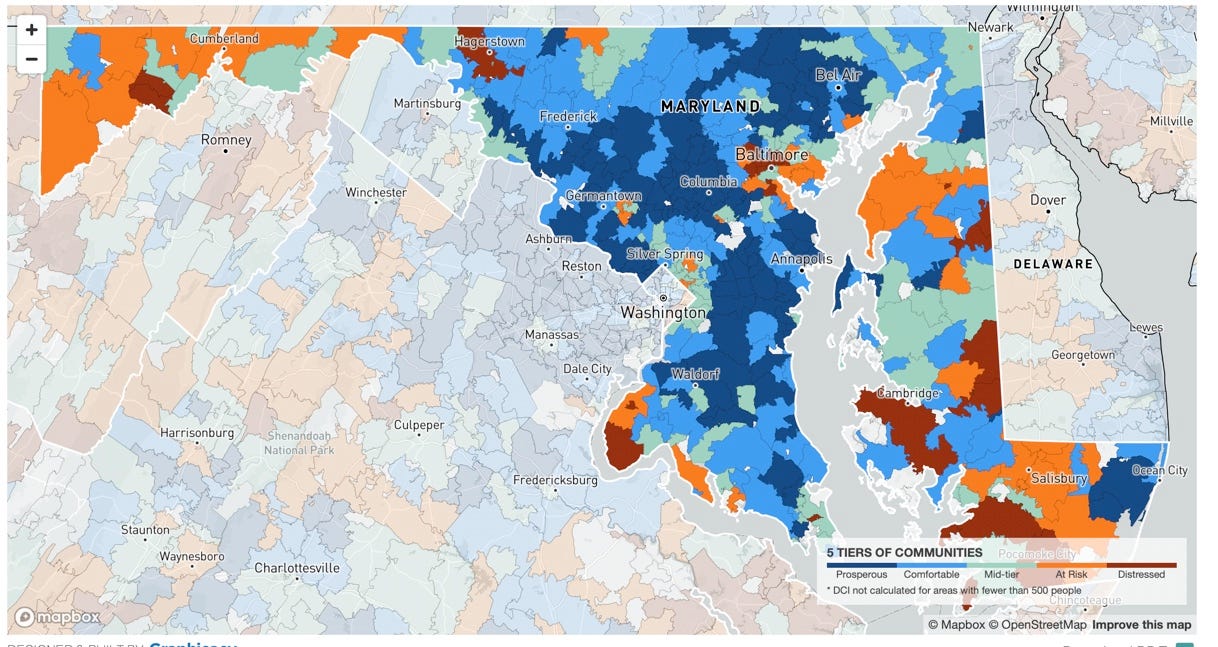

Differences are also pronounced within states. Zooming in on Maryland, for example, you can see many suburban areas outside Washington, D.C. prospering quite well versus areas in my hometown of Baltimore, and other more rural parts of the state and on the Eastern Shore, with much higher levels of distress and risk.

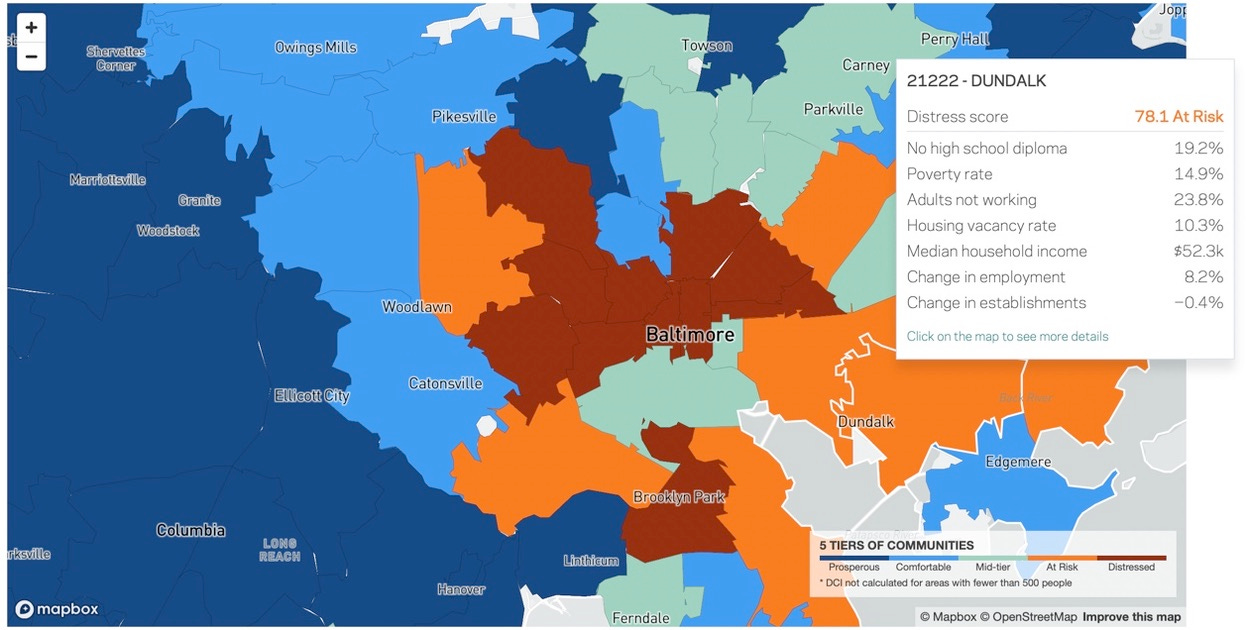

Looking even closer at the Baltimore region below, you’ll see stark lines of economic prosperity and comfort in the northern part of the city and surrounding counties, with deeper economic distress and risk in other neighborhoods to the west and east. The distressed and at-risk distribution covers city populations that are primarily black (such as Freddie Gray’s neighborhood in Sandtown-Winchester, zip code 21217) and those just outside the city that are primarily white working class (such as Dundalk, zip code 21222), along with other mixed-race or heavily Hispanic areas in the area.

Play around with the nice interactive EIG website and you’ll find the exact spatial landscape of opportunity and distress in your region.

The point in examining these maps is that people across the country, and within regions, face starkly different economic environments that often go beyond racial and ethnic lines. Thus, if we want to expand real economic opportunities for all people in all places, policy makers must think in terms of what specifically is needed in multiple environments to revitalize or build up those American communities most at risk or distressed.

In one region, it could mean expansion of existing community college programs or new job training efforts to connect local young people or the unemployed with regional businesses. In another, it could mean building a new hospital or upgrading public utilities and broadband access to help families, schools, and businesses. New public transportation or roads could be used throughout states to better connect those in underdeveloped areas with jobs and opportunities in more developed parts of the state.

How do we do this?

Although Michael Bloomberg’s presidential ambitions were a huge bust, he did put out one of the best place-based policy initiatives of anyone in the Democratic primary. As The New York Times reported in 2020, Bloomberg’s goal was to use federal policy to increase state and local economic development opportunities along with more traditional steps to increase wages and bargaining power for workers:

A shrinking share of America’s counties have generated the bulk of economic growth as the United States recovered from the Great Recession. The activity has been concentrated in metropolitan areas, like Boston, Seattle and San Jose, Calif., that are home to large numbers of college-educated workers.

Mr. Bloomberg’s plan to reverse those trends would lean heavily on efforts to improve education and skills training for Americans across the country, along with “billions of dollars” in federal spending on research and development, and on infrastructure projects like rural broadband development. It would create “business resource centers” to help entrepreneurs gain access to capital to start businesses, and it would steer more money to community colleges and apprenticeship programs.

Mr. Bloomberg also said he would raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour from $7.25 and expand the earned-income tax credit, which raises the take-home pay of low-income workers. He said he would give all workers, including those in the gig economy, the right to organize labor unions and bargain collectively, and he said he would end noncompete agreements for low- and middle-income workers. Such agreements, which restrict worker movement, have been criticized as preventing employees from obtaining raises.

He would also create a “place-based” earned-income credit to encourage investment in distressed communities.

The Brookings Institution has also put forth a number of solid place-based ideas for addressing regional inequalities through steps like connecting university resources to job creation and manufacturing opportunities in distressed communities. The Brookings approach doesn’t ignore race either, and argues that the spatial distribution and concentration of many black populations requires place-based approaches to help increase equal opportunity for those communities historically marginalized. Likewise, Congressman Jim Clyburn’s great place-based “10-20-30” formula seeks to allocate a minimum of 10 percent of government investments to those counties where 20 percent or more of the population has been living below the poverty line for the last 30 years—about 400 counties.

These counties mired in persistent poverty are as diverse as our great nation; African American communities in Mississippi and South Carolina, Appalachian communities in Kentucky and North Carolina, Native American communities in South Dakota and Alaska, and Latino communities in Arizona and New Mexico. They lack access to quality schools, affordable quality health care and adequate job opportunities.

Unlike strictly race-based policies, place-based policies like these seek to include and target everyone at risk of falling behind, regardless of their demographic profile or background.

This place-based approach makes far more sense in practical political terms since it avoids unnecessary racial divisions that weigh down our politics by shifting public attention and focus to challenges that people everywhere may experience—underinvestment, a lack of jobs and public services, attendant social problems, and few reasons or incentives for young people to stay and live in their communities. If we want to move forward as one nation, we need a common program and politics that brings people together around ideas to help less fortunate Americans in all places, rather than a race-based one that drives working people apart while producing limited success and inviting constant legal challenge.

It’s politically obtuse and morally suspect to ask voters to get behind a program that offers governmental benefits and investments primarily to members of one group but not others based on their race, gender, religion, or nationality. Place-based policies solve this political challenge and therefore provide a better path forward for building majority support for policies that create genuine equality.

Let’s make sure all neighborhoods—in all parts of America—have the foundations necessary for economic success.