What’s the Matter with China?

Americans are wary of China but do not have a common understanding of how to respond to rising challenges.

As policy experts across the spectrum in the United States declare loudly that China poses a genuine threat to America—economically, militarily, and technologically—Americans themselves remain divided on the matter, particularly along partisan lines. Despite two consecutive administrations trying to build a united front against Chinese aggression and attempts at global domination, the public lacks a clear understanding about what we are doing as a nation in relation to China.

America still needs a national strategy and economic plan to compete with China that voters understand and support.

One thing is clear: Americans increasingly do not trust or like China. Pew’s study from March of this year shows the sharp erosion of attitudes toward China:

Today, 67 percent of Americans have “cold” feelings toward China on a “feeling thermometer,” rating the country less than 50 on a 0 to 100 scale. This is up from just 46 percent who said the same in 2018. The intensity of these negative feelings has also increased: The share who say they have “very cold” feelings toward China (0-24 on the same scale) has roughly doubled from 23 percent to 47 percent.

This shift in negative feelings cuts across the partisan spectrum with 61 percent of Democrats and 79 percent of Republicans now holding “cold” feelings toward China—up from 38 percent and 57 percent, respectively, in 2018. But looking at the left of the chart below, Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say that “limiting China’s power and influence” should be a top national priority, even as most Americans agree that they don't like China.

Digging deeper into the issue of why this is the case, Pew finds that Americans are concerned about a range of issues from human rights abuses to China’s economic power to its authoritarian political system, with no one set of issues dominating public concerns over any other. “Things are changing with China and we don’t like it,” is the basic conclusion from these data.

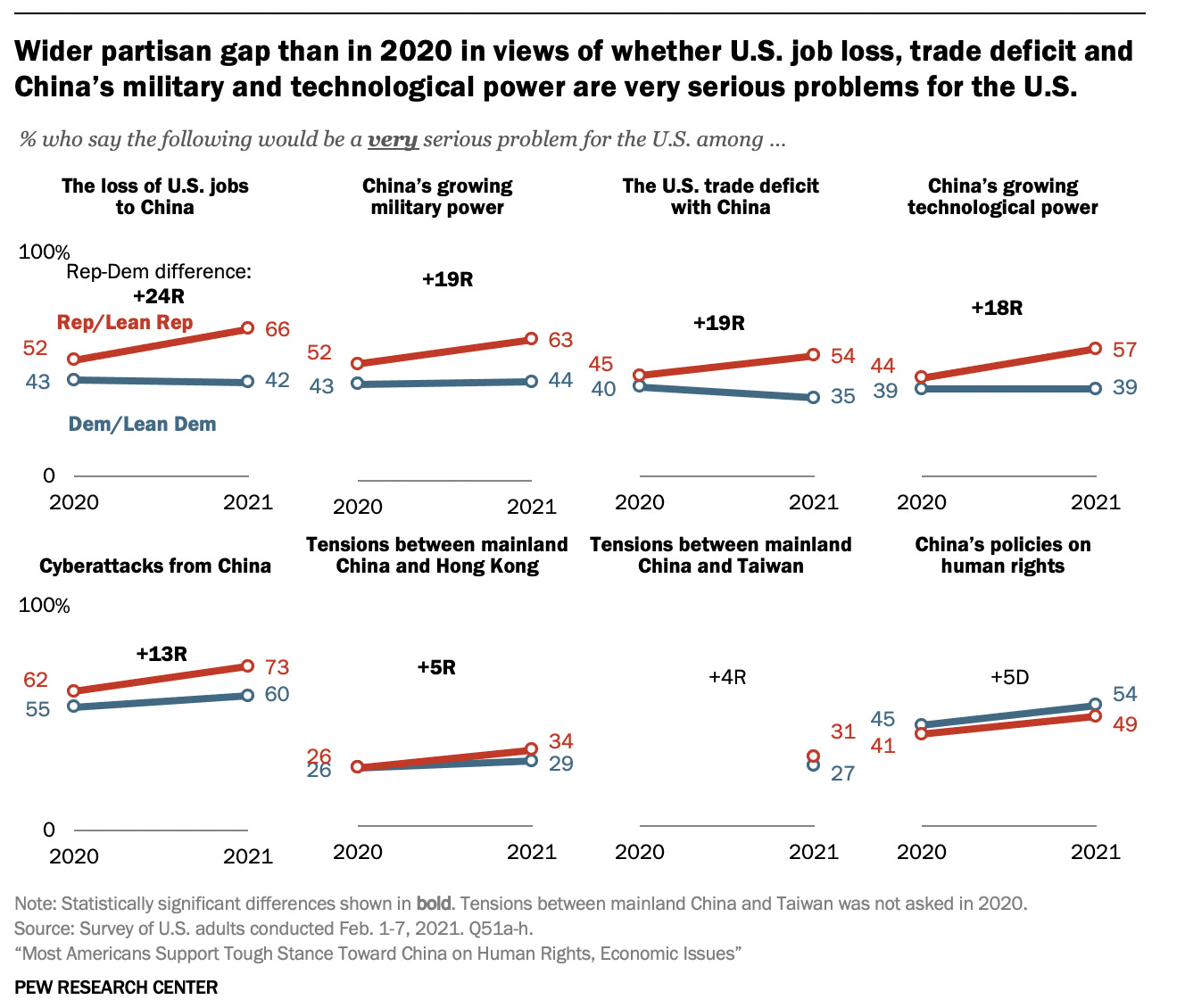

Looking again at partisan responses to these rising challenges in the chart above, Republicans clearly express greater concerns than do Democrats about issues such as the loss of jobs to China, China’s growing military power, the U.S. trade deficit with China, and China’s growing technological power. Human rights issues, and cyberattacks to some extent, are the only areas of concern about China that seem to unite Americans across party lines.

But concerns about human rights issues and cyberattacks—as important as they are—cannot sustain a national response to China’s rising dominance.

Debates about a looming “new Cold War” with China overshadow many legitimate public discussions that will be necessary to build a common approach to national rebuilding and competition with China. Questions to answer include:

What is our basic approach to China—investing in ourselves or taking more forceful international actions to block China's ascent? What are the key policy priorities for fighting back against China? How do we stand up for ourselves economically and politically without increasing military or other tensions that no one wants? Is it even possible to cooperate with China given its self-interests and strategic goals?

The current Biden administration formulation of “compete, confront, cooperate” may work at international summits and conferences. But it has not yet provided Americans with a clear and concise strategy for what we are doing as a nation to deal with China. Neither did President Trump’s unfocused belligerence with China on trade and other matters.

Our national political, business, and human rights leaders therefore will need far more in-depth discussions with Americans about what we are seeking to achieve versus China and how we plan to get there. Otherwise, we risk falling behind globally and fracturing politically about how best to arrest this decline.