A Deeper Look at America’s Anti-Establishment Moment

And how the Democrats might navigate it.

As we enter 2026, the United States is preparing to celebrate its 250th year of existence. Such a milestone presents an opportunity for Americans to take stock of how far the country has come and debate where it should go next. Much of that determination rests on how they feel about the state of things today. A large majority of Americans across the political spectrum believe the U.S. is on the wrong track, and have believed so since at least the start of the Great Recession.

Correspondingly, there also exists a long-festering animus toward the country’s institutions and elites. Such attitudes are not unique to America, but they have been a dominant political force here over the past 50 years—and are thus worth examining more closely as the country sets its course for the next 50.

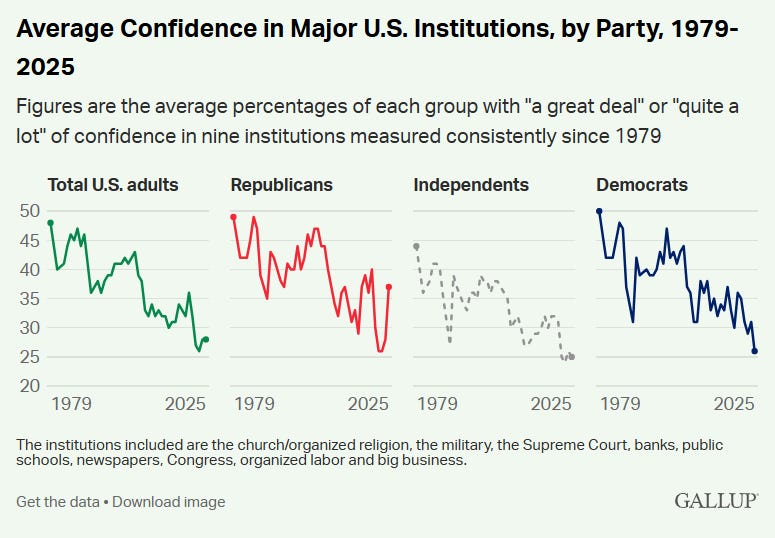

Gallup has tracked public confidence in major U.S. institutions since 1979. Back then, nearly half (48 percent) of Americans, including 49 percent of Republicans and 50 percent of Democrats, had either “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in nine key institutions, including banks, organized labor, the church, and Congress. Today, that figure is just 28 percent overall and an even lower 26 percent among Democrats, an all-time low (and matched by Republicans in both 2022 and 2023).

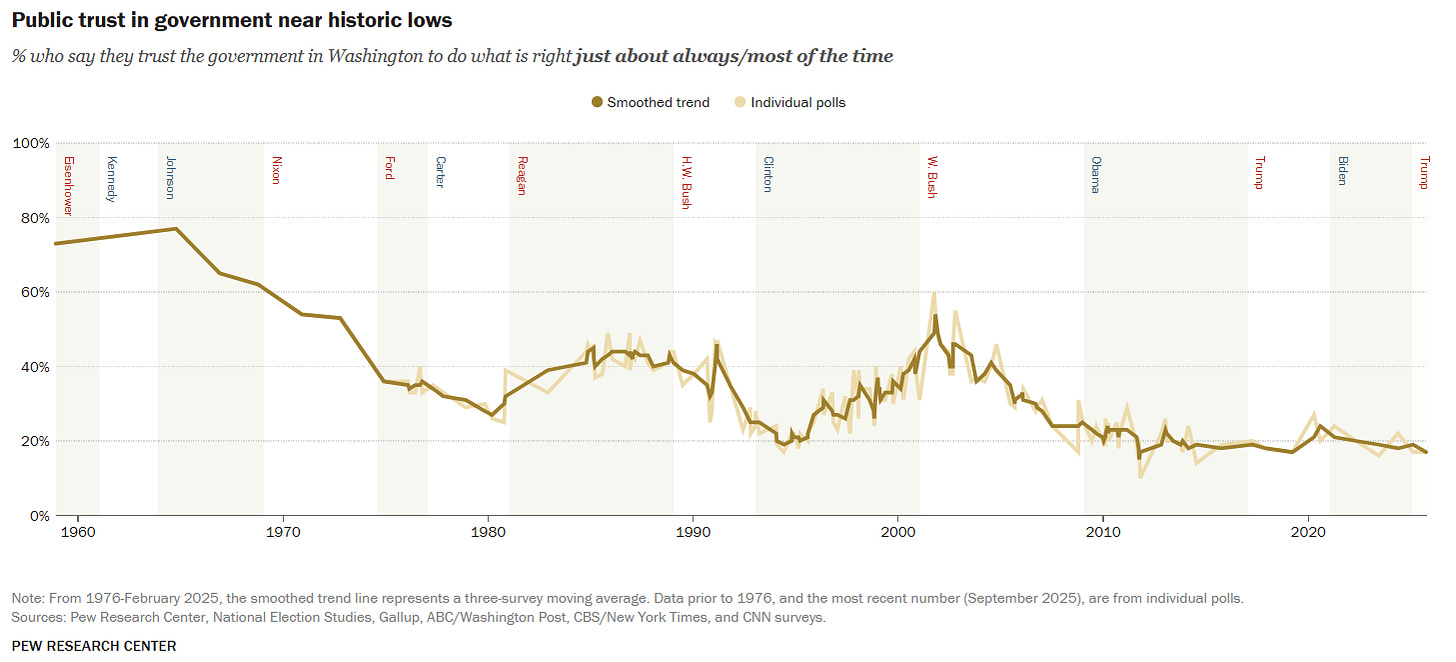

Trust in the federal government, specifically, is also at historic lows. Pew Research has analyzed survey data since 1958 gauging public trust in “the government in Washington to do what is right just about always/most of the time.” During the Johnson administration, that figure hit a high of 77 percent. Since then, however, that sentiment has declined considerably, with only occasional periods of renewed trust (such as right after the September 11 attacks). Today, a paltry 17 percent of Americans have faith in Washington to regularly do the right thing.

Following George W. Bush’s presidency, which included the widely unpopular Iraq war and a global stock market crash, public trust cratered to just 15 percent, spurring a new era of populism in America. The first prominent politician to tap into Americans’ cynicism around this time was Barack Obama, who fashioned himself as an outsider running against Washington but who also offered voters hope that a better future with more responsive institutions was possible. By the end of his time in office, though, many Americans remained cynical, leading to the election of a more pugilistic president with a penchant for picking fights with elites and experts and set on laying waste to several of the country’s institutions altogether.

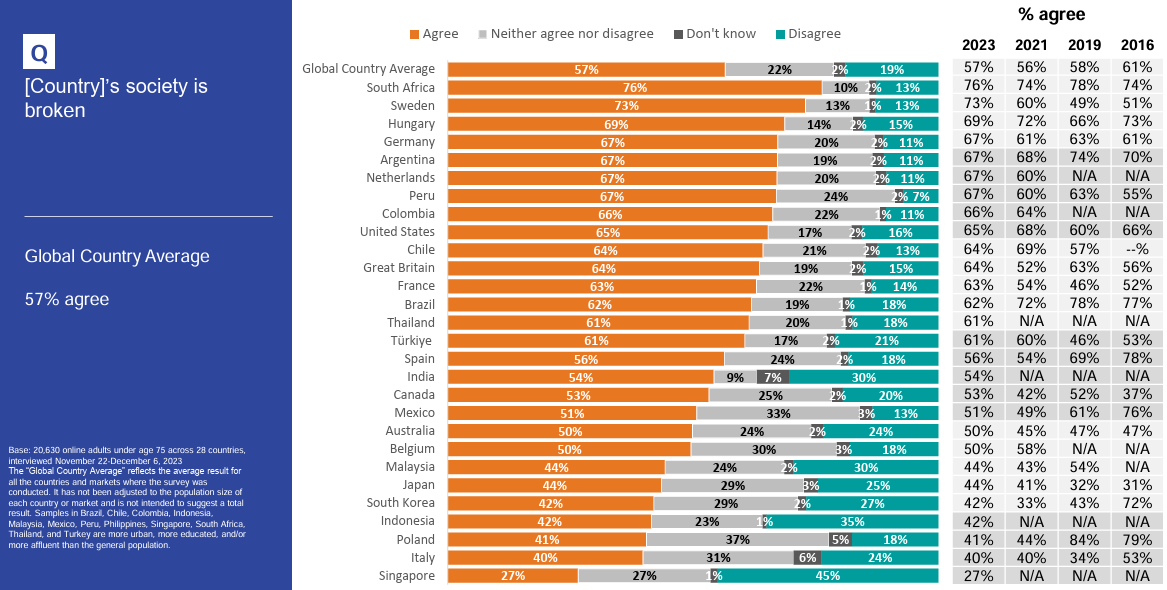

Americans’ desire for substantial change has persisted since Donald Trump’s first election and was evident once again in the lead-up to—and aftermath of—the 2024 election. Early that year, Ipsos released the results of a survey examining populist, anti-elitist, and nativist attitudes across 28 different countries on four continents, including the U.S. In the aggregate, 57 percent of respondents agreed that their country was broken, but that number was 65 percent among Americans, ranking ninth among all countries in the survey.1

In the same survey, Americans also reported believing:

The country’s economy is rigged to advantage the rich and powerful (66 percent);

Traditional parties and politicians don’t care about people like me (65 percent);

The U.S. needs a strong leader to take the country back from the rich and powerful (66 percent);

Experts in this country don’t understand the lives of people like me (63 percent);

The political and economic elite don’t care about hard-working people (69 percent);

The main divide in our society is between ordinary citizens and the political and economic elite (60 percent); and

The “elites” in America tend to make decisions based on their own interests and the needs of the rest of the people don’t matter (54 percent).

Notably, the U.S. stood apart from other countries on some of these questions, including agreeing at a far lower rate than the overall survey results with statements like “to fix our country, we need a strong leader willing to break the rules” (40 percent agreed in the U.S., the seventh-lowest among all countries, versus 48 percent overall), and “the U.S. would be stronger if we stopped immigration (33 percent in the U.S. versus 43 percent overall). Still, the survey results point to a similar trend: anti-elite and anti-establishment sentiments are strong in the U.S. and many other countries.

Post-election data also highlighted these frustrations. The AP VoteCast survey asked voters how much change they wanted to see in “how the country is run.” A whopping 83 percent supported either “substantial change” or “complete and total upheaval”—and they broke for Trump by 15 points.

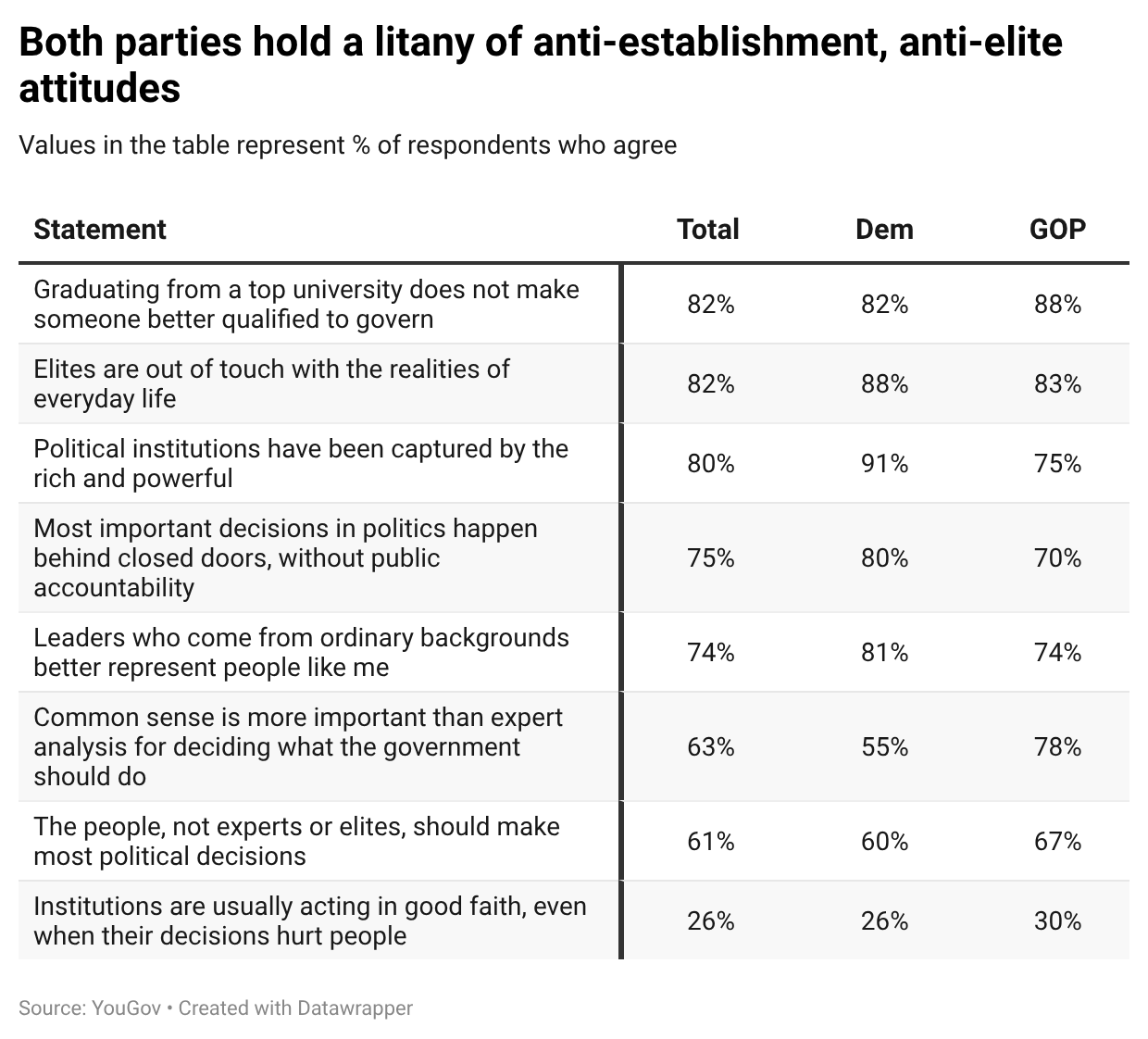

More recently, YouGov asked a battery of questions related to anti-establishment attitudes, and there was broad, bipartisan frustration with not just the government but elites and institutions more broadly.

Both Democrats and Republicans are skeptical that elites possess knowledge or enlightenment that makes them better suited to make decisions for the country than regular people could. While many experts and members of the educated class will no doubt dispute this idea, it’s worth asking why so many people, across political party, age, race, gender, economic class, and several other dimensions, have come to believe these things.

Back in May, I wrote that the political party that understands this moment and more adequately addresses voters’ frustrations is likely to have success in coming era of American politics. Though Democrats briefly signaled that they wanted to be that party under Barack Obama, Republicans picked up the mantle in 2016 and have yet to surrender it. Moreover, as Democrats have increasingly become the party of affluent, college-educated, cosmopolitan voters, they may have to work harder to convince everyday Americans they care about their interests and don’t reflexively defend the status quo or establishment.

At the same time, frustration with the establishment does not mean voters are willing to lean fully into left-wing cultural politics or populism, either. As the recent report Deciding to Win noted:

…anti-establishment rhetoric can’t fix problems caused by unpopular position-taking. Democratic candidates who criticize the establishment but run on unpopular positions on issues that are important to voters, like immigration or public safety, tend to be poor electoral performers. Ultimately, anti-establishment rhetoric is a complement to a popular policy agenda, not a substitute for it.

And:

…frustrations with the status quo are not the same as a desire for socialism. While many voters feel frustrated with the status quo and their economic situation, large majorities of Americans continue to have positive views of capitalism, and large majorities continue to have negative views of socialism.

As the party that has long believed the government can help improve people’s lives, many Democrats abhor Trump’s moves to remake (and often gut) federal agencies and departments. It would be unreasonable to suggest the party replicate his tactics to find success. But a full-throated defense of elites, experts, and institutions—or a descent into the left-wing equivalent of Trumpism—in this moment is not politically prudent either. Whether it’s their candidates this year or their eventual 2028 nominee, Democrats would do well to address these anti-establishment frustrations by offering a vision for reforming America’s institutions and restoring trust in them.

Similarly, across Ipsos’ surveys since 2016, an average of 65 percent of Americans agreed that the country is broken, the sixth-highest rate among all countries.

It’s not hard to understand the cynicism and scorn for the elite. They have earned it. Every ounce of it.

Democrats, as the party of the elite, wring their hands and blame the people. The people just don’t understand the superior intellect and morality of the professors, the career government workers, and the NGO’s. The people must be made to respect their betters. Then all will be well.

The “elite” will never, ever look in the mirror for the source of the problem.

Your last paragraph is the key. If Democrats are the party that believes the government can improve people’s lives, then the job isn’t to defend institutions as they are. It’s to show, concretely, how the government can work better. In ways ordinary people can see and feel.

The measures you cite don’t just say “people are mad.” They say something stronger, the system looks broken in a long-run way. The Pew trust curve is the real key. Trust was high in the late 1950s through mid-1960s, then it breaks in the late 60s/70s and never returns to the post World War II high. Since then we’ve had temporary bumps (Reagan, late Clinton, post-9/11), but no durable rebuild. This includes from 2008 to now where we have had both parties, and vastly different presidents major laws passed like Obamacare. Nothing moved the trust number which tells you that the problem is deep and structural.

That pattern matters because it suggests this isn’t going to be fixed by messaging, or by one charismatic leader, or even by a single policy win. It’s a system problem, probably multiple reinforcing “drivers” failing at once: visible competence, truth lining up with what people can observe, real accountability, rules people can plan around, basic safety/assurance, institutions that lower the temperature instead of raising it.

So yes: Democrats need a vision for reform. But it has to be framed as operational repair. how the system will become more reliable. Additionally it has to be consistent long enough to rebuild trust as a stock, not just a mood. That almost certainly requires reforms that can survive beyond one administration, which means some bipartisan durability whether anyone likes that or not