During the Trump era, the Democratic Party has stumbled on a number of issues, perhaps none more than immigration and crime. Back in February, I outlined how in recent years the party has shifted markedly to the left on immigration, specifically, shedding the more moderate, balanced approaches of presidents like Bill Clinton and Barack Obama in favor of one that was more in vogue with advocacy groups. Many high-profile Democrats began endorsing, tacitly or explicitly, an open-borders policy.

But as the country faced an unprecedented surge in migration under Joe Biden’s presidency, Americans swiftly rebelled against that kind of thinking. Polling showed that after decades of growing support for increasing immigration levels and waning support for decreasing them, both trendlines reversed—hard—during Biden’s term. His handling of immigration was ultimately a major reason why Trump won last year, and voters today say they overwhelmingly trust Republicans more than Democrats on the issue.

Though Americans typically do not consider crime and public safety to be as big a problem as immigration, these issues have become yet another albatross for Democrats under Trump’s reign. As he has ramped up an anti-crime push in cities and states across the country, many in the party have resorted to defending relatively lower levels of crime—levels that still are not acceptable to many people. Americans today trust Republicans over Democrats to handle crime to an even greater degree than they do immigration.

All this points to a broader issue for team blue: they’ve lost the confidence of the public on issues related to social order. This reflects a similar struggle for many governing parties in Europe. New analysis from political economist Laurenz Guenther found that while voters and mainstream politicians have often been aligned on tax-and-spend economic issues—favoring more spending and broadened public programs—there has been a growing gap between them on sociocultural issues like criminal justice and immigration. The Financial Times’ John Burn-Murdoch recently reviewed the research:

Western publics have long desired greater emphasis on order, control and cultural integration. Their politicians have tilted in the opposite direction, favouring more inclusive and permissive approaches.

The result is the opening up of a wide “representation gap”—a space on the political map with large numbers of voters but few mainstream politicians or parties—into which the populist right is now rapidly expanding as cultural issues rise in salience.

Burn-Murdoch added that his own updated analyses of this question shows these same dynamics at play in the United States,

where the average voter’s preferences on immigration are close to those of Republican politicians, but far more conservative than those of Democratic party elites. […] A similar pattern is clear with crime, where rates of arrest and prosecution have fallen in several countries and lower-level disorder is on the rise. Sustained failure to curb these trends under governments of both the centre left and centre right has signalled to the public that the political class either doesn’t see this as a problem or is incapable of addressing it.

This perception strikes at the core of voters’ anxieties about the state of the country and their communities in what feels to many of them like an increasingly unstable time. And if Democrats aren’t willing or able to offer more reassuring answers, they can’t be surprised when people turn to figures like Trump.

The party is thus in urgent need of a new approach to addressing social disorder, and there are some good examples from the recent past of what this path forward could look like.

Denmark

Two weeks after I published my February immigration piece, the estimable David Leonhardt wrote a lengthy treatise examining how Denmark has managed to avoid the fate of other European countries where a populist, nativist right is surging. He zeroed in on a clear factor: the Danish center-left party, the Social Democrats, chose to use its power to tackle the immigration issue before the right could weaponize it.

Leonhardt notes that Denmark’s liberals have succeeded in pursuing much of their domestic agenda—continuing to provide a generous welfare state for its people, expanding worker protections, combatting climate change, and more—precisely because they took a very different approach to immigration:

Nearly a decade ago, after a surge in migration caused by wars in Libya and Syria, [Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen] and her allies changed the Social Democrats’ position to be much more restrictive. They called for lower levels of immigration, more aggressive efforts to integrate immigrants and the rapid deportation of people who enter illegally. While in power, the party has enacted these policies. Denmark continues to admit immigrants, and its population grows more diverse every year. But the changes are happening more slowly than elsewhere.

These policies made Denmark an object of scorn among many progressives elsewhere. Critics described the Social Democrats as monstrous, racist and reactionary, arguing that they had effectively become a right-wing party on this issue. To Frederiksen and her aides, however, a tough immigration policy is not a violation of progressivism; to the contrary, they see the two as intertwined… She described the issue as the main reason that her party returned to power and has remained in office even as the left has flailed elsewhere.

Leftist politics depend on collective solutions in which voters feel part of a shared community or nation, she explained. Otherwise, they will not accept the high taxes that pay for a strong welfare state… High levels of immigration can undermine this cohesion, she says, while imposing burdens on the working class that more affluent voters largely escape, such as strained benefit programs, crowded schools and increased competition for housing and blue-collar jobs.

Frederiksen added, as if speaking directly to the Democrats, “Working-class families know this from experience. Affluent leftists pretend otherwise and then lecture less privileged voters about their supposed intolerance.”

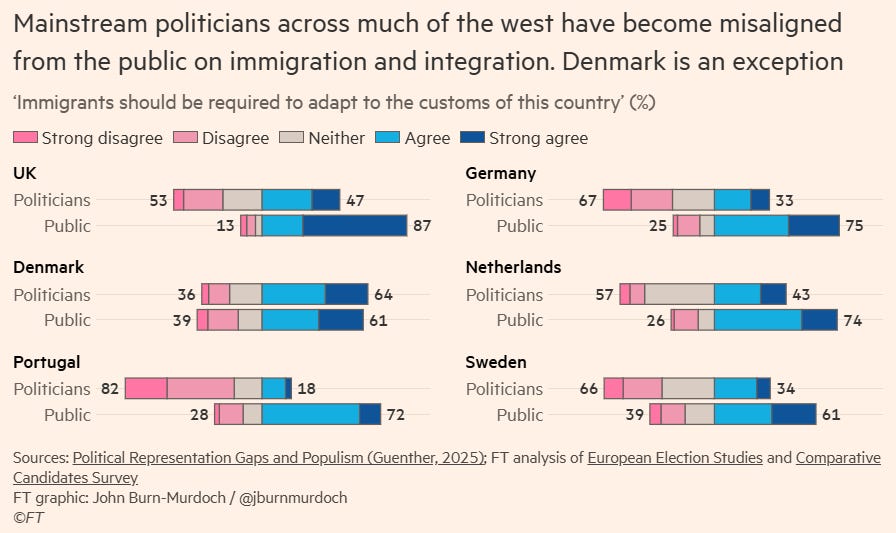

Burn-Murdoch’s data confirms that mainstream parties in Denmark have remained much closer to the public’s views on immigration—specifically, its desire for migrants to “adapt to the customs of this country”—than they have in other countries that have witnessed the rise of a populist right.

Finally, Leonhardt offers this important observation:

Immigration has often been chaotic, extralegal and more rapid than voters want. The citizens of Europe, the United States and other countries were never directly asked whether they wanted to admit millions more people, and they probably would have said no if the question had appeared on a ballot. Instead, they revolted after the fact…

For progressives in the United States, Denmark may not be an especially comfortable exemplar. The cruel aspects of Trump’s immigration policy have understandably outraged many people. But…Denmark offers a glimpse at what a different version of the left can look like—more working-class, more community-focused and more restrictive on immigration. Frederiksen and her Social Democrats have confronted their peers elsewhere with a question: In the modern age, is a restrictionist border policy a prerequisite for successful modern progressivism?

Though Denmark continues to admit a modest level of immigrants each year, it is clear that the ruling Social Democrats believe their rethinking of immigration policy is not just be a matter of good politics—though it is certainly one consideration—but also the right thing to do by the nation’s citizens.

Poland

Since Denmark set the example for how center-left parties in Western democracies can responsibly tackle the immigration issue, others have begun to follow suit, including Poland. Like other European countries, Poland has experienced a severe backlash over its immigration levels. Writing recently for Persuasion, Leo Greenberg examined how the country’s centrist governing coalition has tried to navigate this moment:

The new liberal coalition faced two border crises, public sentiment that had moved sharply against non-Western migrants, the ever-present threat of the [populist-right party] PiS’s return to power, and the need to repair Poland’s relationship with European institutions. Their response was the 2025–30 Migration Strategy, issued in late 2024. The Strategy outlined a points-based system to attract economic migration and promised to construct integration centers to help immigrants learn Polish and navigate social services…

Poland’s former Justice Minister, Adam Bodnar, justifies the policy by arguing: “if you are not controlling the border, it means that you are not effective…the effectiveness of the government should be cherished in defending liberal democracy, or you create a chance for voices against liberal democracy to create a fully illiberal project.” The government’s limitation of human rights, in his eyes, was a necessary tool to keep populists out of power.

Crucially, though, Duszczyk does not see the moves solely as concessions to political necessity. Rather, he sees them as part of the necessary work of statecraft to preserve a sense of social cohesion. Change that is too fast or too unpopular—especially for a country with a history of foreign exploitation, painful lockdowns during COVID, and a war on its border—risks failing the first test of government: providing people with a strong sense of security.

Sound familiar?

Poland’s Danish-like approach highlights two core pieces of any sensible immigration policy in the West. The first is measures supporting the assimilation and integration of new migrants to help bolster social cohesion. The desire for such a policy is illustrated in Burn-Murdoch’s survey data, which shows that no less than 60 percent of people in six different European countries said this should be a requirement.1 And the second is an affirmative belief that controlling a country’s borders and the flow of people across them is good.

Representative Jake Auchincloss

To be sure, some Democrats, such as Senator Ruben Gallego, have vocally urged the party to pivot to the center on issues like immigration and crime and promoted reasonably tenable reform plans to achieve this. One who has been grappling recently with this bigger picture—with the broader stakes of social disorder—is Congressman Jake Auchincloss, who represents Massachusetts’ Fourth District.

At the core of Auchincloss’s theory is what he calls “cost disease,” the seemingly never-ending rise of costs in sectors like housing, utilities, and healthcare. As certain routine expenses become more difficult for Americans to pay, many feel that their lives—and perhaps by extension the world the round them—are becoming less stable and, thus, less secure. Auchincloss identified the inflation that plagued the second half of Biden’s presidency as a driver of this and has argued that Democrats lost in 2024 because “we were not perceived as upholding social order.”

Auchincloss has also chastised his party for its action (or inaction) on recent, related issues, like some Democratic-run cities and states keeping schools closed during the Covid pandemic even after public health authorities said it was safe to re-open them. He believes these decisions were “too focused on process, not enough on outcomes that mattered, which was getting kids back in schools. And there was a condescending attitude to parents who were rightfully frustrated watching kids atrophy at home.” The pandemic itself engendered a stronger sense of social disorder for many people, and the indefinite restrictions on public life did not seem to make them feel otherwise—and may have even achieved the opposite.

Additionally, the congressman has taken to task public officials who tolerate other forms of public disorder as a fact of life, including homelessness and crime, criticizing his party for not being strong enough on these issues and arguing that, for example, cities “should be able to clear…open air encampments.” It wasn’t long ago that such sentiments were not only uncontroversial but widely shared in his party.

At present, Americans just don’t seem to buy that Democrats have substantively shifted in a new direction on these issues, likely a lingering effect of Biden’s tenure. Take immigration. Voters sensed an apparent lack of desire from him to crack down on the surge of border crossings until it became a political liability. At the eleventh hour, his administration pushed for a legislative fix, but even after Trump derailed bipartisan congressional negotiations and Democrats cried foul, voters still blamed Biden more for the bill’s failure than they did Trump.

The writer Josh Barro also recently observed that while some in the party have sought much-needed fixes to broken aspects of the immigration system such as the asylum process, there still isn’t much of an appetite for addressing harder questions about deportations and illegal immigration other than denouncing Trump. And this likely adds to the public’s continued skepticism that Democrats have really learned much since 2024.

On crime, the decision of several “progressive prosecutors” in major American cities to begin decriminalizing certain offenses toward the end of the previous decade also seems to have turned some voters off to the party’s governance, especially after the subsequent rise in violent crime during the early years of the pandemic. Though research suggests a complicated causal link between these prosecutorial changes and the crime trends, voters nonetheless associated the two and delivered swift blowback to those politicians. They continue to view crime as a serious problem—and, for now, trust Republicans more.

Democrats needn’t align themselves wholly behind Trump’s policies or rhetoric to show they take Americans’ concerns seriously and are making real changes to address them. (It’s not as though voters don’t have issues with some of his policies as well.) But the party also can’t avoid difficult conversations or remain uncritical of certain shibboleths if it wishes to regain voters’ trust.

Any path forward for them must include demonstrating convincing evidence of a shift from the past: a clear intolerance for social disorder, an acknowledgement that Americans have a right to be concerned about their borders and the pace of immigration without being labeled as xenophobic, and an understanding that building a more progressive society requires high levels of trust—and order.

Democrats would do well to remember that President Obama also advocated for this in his immigration reform proposals.

Dems should listen to the author. Assuming the West is still the West in a century, mass migration will be second only to slavery, in lousy public policy. All over the West, citizens living with the ramifications have been screaming for relief, as Progressives stuff ever more migrants down their throats. All without adequate housing, healthcare and speciality teachers as they seek to Arabnize the West.

The term has nothing to do with ethnicity, but rather the notion a small subset of people should be waited on by armies of round the clock servants. In Dubai for my husband's job, more than 2 decades ago, we were amazed at the gleaming city rising out of of the sand. We were even more amazed to find we were obviously visiting a modern day Plantation, and no one seemed to care.

Many wealthy Arab nations have tiny populations of actual citizens, surround by legions of imported "workers". For a family of 3, our hotel room had a butler, multiple maids and someone devoted to our food needs, because picking up the phone to order room service, calling the concierge for dinner reservations or actually opening the minibar was, evidently, a bridge too far for some. I declined the offer of a round the clock nannies.

Over the course of a week, our butler patiently waited by the elevator to ensure I never needed to carry my own packages or open our hotel room door. He seemed genuinely perplexed when I explained I could draw my own bath and add the bath oil, all on my own.

The situation that really drove home the Twilight Zone existence, was a young Bedouin on the beach, with a camel. 15 or 16 years old, he spoke broken English, and as he gave my son a camel ride, I asked if camels were kept in stables like horses, and did he live nearby? He explained he and the camel lived on the beach, down the way with a few others, who also gave tourists rides. A fountain, several blocks away provided water. No mention of restroom facilities, in the shadow of our hotel, where I could have comfortably hosted cocktails for 12 people in our bathroom. He explained he would stay for a year or two, before a brother would take his place. Dubai can be 120 degrees+ in the summer.

People usually react to Arabnizing in one of 2 ways. This is a greatest idea since sliced bread or this a very, very, very bad way to operate a society. Guess the breakdown by political party? The Washington Post, or one of its' ilk, recently ran a piece on the plight of a DC power couple, whose $400K kitchen remodel was heartbreakingly on hold, due to a lack of migrant labor. This as Nazi Reps caused nannies, all over the neighborhood, to flee with no notice to their employers! Oh the horror.

If Dems do not wake up and have a come to Jesus immigration moment, the best they can hope for is to exist as a cartoon party. All over the West, citizens have reached their boiling point. The statistics are abysmal, across the board. Mass migration works for no one but exploitive employers, criminal migrants or those seeking only generous welfare states, and political parties hoping to import future voters. In the US, are obviously meant to prop up sagging Blue State populations for apportionment. Nowhere on the list are average citizens found. If mass migration is the hill on which Dems wish to die, voters will likely comply.

There is another perspective for these vexing issues - that policies regarding open borders, decriminalization of crime, support of homelessness, DEI, fentanyl, and the transing of children are meant to promote social disorder. Seriously, if you were tasked to shred social cohesion what would you do differently?