“It’s All the Other Side’s Fault”

How we convince ourselves our opponents are dumb and evil—and we’re blameless.

When there’s a dangerous fire, most people’s first instinct is to grab a hose, not waste time trying to figure out how it started. Many believe the same about our politics: stop the intellectual analysis and “both-sidesing” and just help us defeat the bad actors. You hear it from Democrats and anti-Trump folks, and you hear it from Republicans and others angry at the left.

But toxic polarization isn’t a normal fire. It’s a decades-long, slowly spreading blaze that many of us unknowingly feed every day—with contempt, cheap shots, and worst-case stories about “them.” Many of us tell ourselves stories about how ignorant, misinformed, and even evil the other “side” is, which acts as an accelerant. Our contempt and fear lead to more support for increasingly hostile, defeat-them-at-all-costs approaches to politics and public life. And if we can’t figure out a way to put out this fire, it will put our experiment in self-government at grave risk.

Can Both Sides Be Right?

A major barrier to reducing toxic polarization is that so many of us—especially those who are highly politically involved—see our current toxic conflict as clearly the other side’s fault.

Many Republicans point to Democrats’ large and rapid attitudinal shifts on issues like immigration, abortion, gender, policing, and more, shifts they argue haven’t been mirrored in scale on the right. These changes, compounded by what they perceive as harsh moral judgment from the left, have led many to conclude the left caused this conflict.

On the other side, Democrats have become infuriated by Trump’s contemptuous behaviors, rule-breaking, and refusal to accept the 2020 election. They believe there is no Democratic version of someone with Trump’s divisive personality and penchant for defying democratic norms, and this leads many to conclude the right caused this conflict.

People in both groups focus on the grievances that alarm them most but often struggle to understand what bothers their adversaries. From the outside, our opponents’ complaints can look minor, silly, or misinformed compared to our concerns, which we (naturally) see as legitimate and based in reality. The more we subscribe to these narratives, the more we risk becoming arrogant, convinced that “you’d have to be an idiot” not to see which group is worse and more at fault for our conflict and division. All this serves to fan the flames of toxic polarization.

Still, it’s important to acknowledge that these competing narratives are built on true foundations. Regardless of which group’s grievances are more defensible, the primary “us vs. them” narratives rest on logically defensible foundations. There are myriad data points and so many events unfolding around us on a daily basis that nobody can accurately process all of it—at least not in any objective, unbiased way. We thus rely on stories, stereotypes, and heuristics to help us make sense of things. So, even when we agree on the same facts, the specific moral frames through which we process the world can lead to entirely different views of what those facts mean—and what they portend for the future.

This helps explain how rational, well-meaning people can reason their way to polar opposite views that they believe are good and righteous—a dynamic philosopher Kevin Dorst calls “rational polarization.” If we can lower our own arrogance, we might develop greater understanding of people who possess very different values and beliefs and perhaps act in ways that persuade instead of inflame—even as we still push for the causes we believe in.

The Fog of Conflict

Part of the difficulty in recognizing that other people are often more rational than we might think is that toxic conflict deranges our thinking, leading us to adopt overly pessimistic and catastrophizing views about them. Conflict rarely feels complicated when we’re in it. Many of us simply see people on the other side and conclude: they are the aggressors; we are just defending ourselves.

But these simple, black-and-white stories blind us to the complexity of the world and the people in it. As historian Geoffrey Blainey has observed, each side in a war tends to see history through its own eyes. Most serious conflicts have many causes, cross-currents, and feedback loops, which makes it hard for the parties involved to ever get a clear view of the conflict. He writes that “the distinction between warmaker and peacemaker is often a mirage.”

One well-known aspect of conflict that obscures our view of people on the “other side” is the tendency to see them as all the same—as a monolithic, homogeneous mass. This leads to all sorts of misunderstandings, including “perception gaps,” which convince people that the other side is much more extreme than they actually are.

Another confusing aspect of conflict is that people in large groups always possess different traits and exhibit different behaviors. In the US, Democrats and Republicans differ—on average—in background, life experience, values, and moral priorities. This leads to differences in how each group manifests their anger and anxiety and even the assumptions they make about the world. For example, a mostly working-class, blue-collar community is likely to come to these things differently than a mostly college-educated group would. Each group will apply different types of social pressures on its members when it comes to their behavior and how they approach the conflict.

And because these differences are usually substantial, each side can point to “bad things they do that we don’t do” and then treat these things as definitive proof that their opponents are the problem.

But the causes of conflict are often complex, and two groups in conflict will always contribute to it in different ways.1 It’s therefore worth examining some of the ways in which Republicans and Democrats can both arrive at the view that “it’s all the other side’s fault,” depending on which events and group traits they focus on.

1. Perceived support for violence

Many people believe it’s the “other side” that’s more violent—that they are the ones whose supporters are more likely to endorse political violence, or at least more tolerant of such violence.

Many on the left believe that right-wing extremism is by far a much more serious threat than liberal-side extremism. They point to events like the Charlottesville Unite the Right march, the assault on Nancy Pelosi’s husband, murders by far-right extremists (like the 2022 Buffalo, NY, mass murder and the 2019 El Paso, TX, mass murder), and, perhaps most prominently, January 6—the event that, to them, most embodies the violent threat posed by Trump and his diehard supporters.

On the right, many see liberals as the violent ones. Conservatives focus on different events and different manifestations of social disruptions, including things like violence during the 2020 George Floyd protests, aggressive tactics by progressive activists, and, most recently, the assassination of Charlie Kirk. They believe too many liberals either support or tacitly condone militancy and violence.

Sometimes, both groups even find evidence of the other side’s violent nature in the same event. For example, following the assassination attempt on Trump in Pennsylvania, some of his supporters cast blame on liberals, while some liberals pointed to the shooter’s past political activity to score points against Republicans.

Some people react in cruel and callous ways to violence aimed at the “other side,” which their opponents interpret as proof of pervasive sickness and immorality. The result of all this filtering is that both groups can end up genuinely wondering, “Why is the other side so violent? Why do so many of them support violence?”

Influencing these views is an instinct many of us have to downplay the significance of violence associated with our group, even as we consider violence associated with the other side hugely consequential. If someone kills a political figure on the other side, we might be quick to imagine a deranged, mentally unwell individual. But if someone kills a political figure on our side, there can be a strong temptation to give it great meaning and quickly designate “them” as all culpable.

The number of people who have committed politically motivated murder in recent decades is extremely small relative to the size of our population. We should recognize that even in the most unified country, there will always be some people drawn to hate and violence. Moreover, many in the media and political realm vastly overstate the number of Americans who actually support political violence.

It’s natural for violent events to upset and scare us. But we should consider whether we’re overreacting to what are rare incidents of violence, statistically speaking, in an otherwise very peaceful country, and how our tendency to cherry-pick bad behaviors and see the worst in each other can amplify divides—and even lead to self-fulfilling prophecies.

2. Class and cultural stereotypes

The divide is also heavily influenced by education and class. Democrats tend to have higher levels of formal education and are more concentrated in high-income, professional sectors and urban areas. Republicans, by contrast, are overrepresented in working-class, rural, and religious communities and are less likely to hold advanced degrees.

These differences help each side create negative, oversimplified stories about the other.

On the left, it’s common to hear that Republicans and Trump supporters are “anti-science,” easily manipulated, or even in a cult. They’re willfully ignorant, duped by conspiracy theories, or too intellectually backward to see what’s obvious to “smarter,” more educated people. You’ll find liberals saying things like, “Of course education makes you more politically liberal; that’s because conservatism is backwards.”

On the right, it’s often the inverse: liberals are “out-of-touch elites” captured by academic jargon and niche activist ideas. They’re arrogant, disconnected from the lives of “normal” Americans, and smugly dismissive of, or even hostile toward, people who aren’t like them.

Again, some of these narratives may contain elements of truth—but in the hands of highly angry political actors, they will often involve worst-case interpretations and excessive contempt. What’s missing is empathy and nuance: understanding that, by and large, people on the “other side” have real, defensible fears and frustrations—and that each group’s fears influence the other’s.

3. Accusations of hate

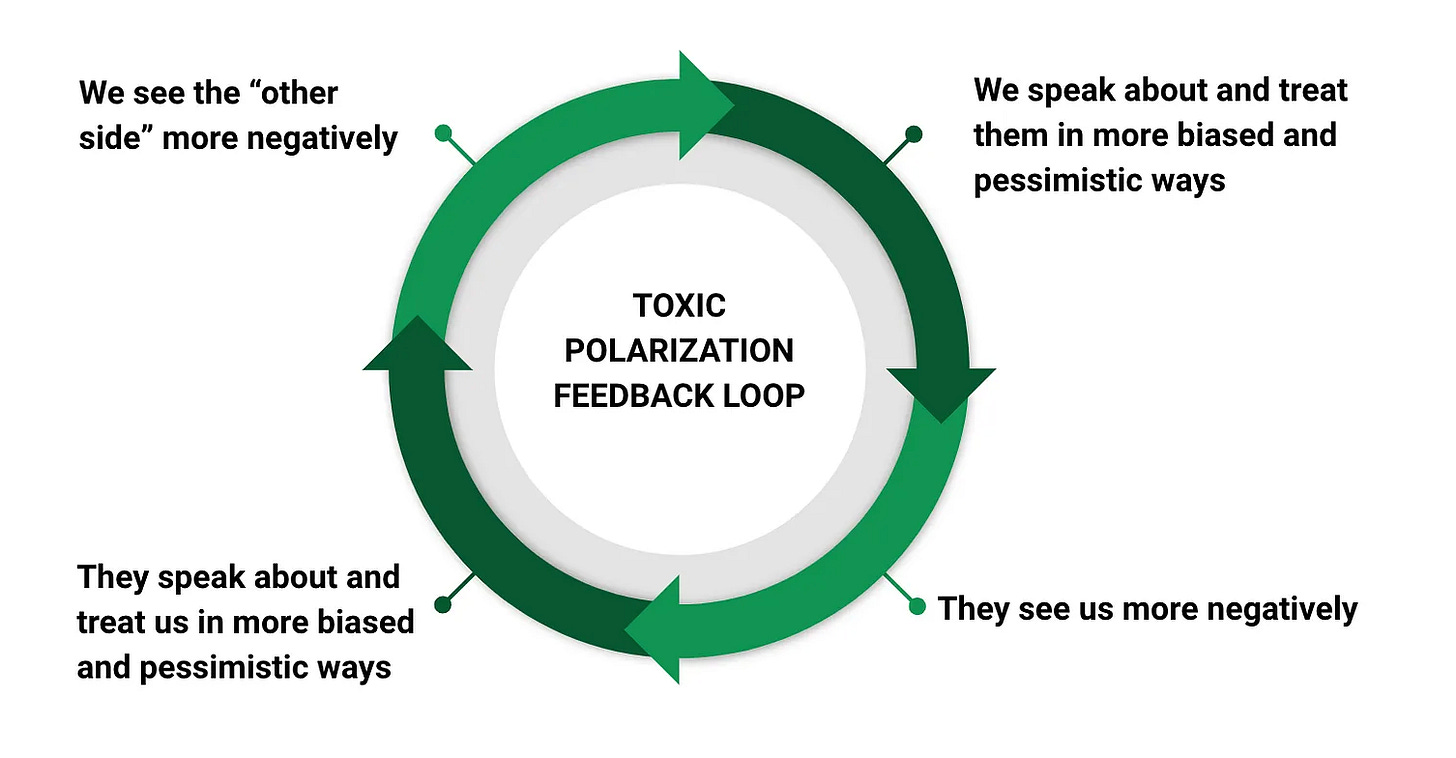

Democrats and Republicans both believe that people on the other side hate them much more than they do. This is one of many self-reinforcing elements of our conflict. When we think, “They hate us,” we are naturally inclined to act in more hostile ways towards “them.” This in turn encourages “them” to treat “us” worse, which makes us treat them worse, and on and on we continue down a doom spiral of toxic conflict.

In the course of working on reducing polarization, I’ve talked to many Republicans who focus on the toxicity they’ve seen and personally experienced from liberals. It’s true that there are many pieces of evidence one can find to support that narrative. For example, surveys show that Democrats are more likely to cut off friendships—or even family members—for political reasons. Some Republicans are tempted to use this as another building block for the “this is all Democrats’ fault” narrative.

However, another way of interpreting that statistic is that many Democrats (and others, too) are turned off by Trump’s divisive personality and by those who support him even in the face of it (or who even emulate his confrontational and even dehumanizing rhetoric).

Group differences can leave many of us concluding with certainty, “See, this shows this is all their fault!” In these moments, we should try our best to strive for humility and to remember that the complexity of the world, and of conflict, makes it easy for us to see what we seek to find but harder to see the best in our adversaries.

4. Cultural vs. political power

Over at least the past few decades, politically liberal people and ideas have come to dominate key cultural institutions like academia, journalism, and the entertainment industry. This imbalance in cultural power has led to an abundance of conservative-aimed insults and provocations generated by the people in those institutions.

That cultural power imbalance sometimes augments other group differences. For example, many conservatives believe there exists a powerful politically liberal establishment—one that at best misunderstands them and at worst disdains them. Feeling like an underdog fighting a vast, culturally dominant adversary can generate more support for an aggressive, contemptuous personality like Trump’s. For many of his supporters, his belligerence isn’t necessarily a flaw but rather a justified form of defiance against an establishment that is entirely against them.

But while liberals have dominated the culture for at least the past decade, they control few levers of political power at this moment. Consider America’s key institutions: the presidency, U.S. Senate, U.S. House, Supreme Court, governorships, and state legislatures. Republicans have more power than Democrats in every single one, and many Democrats fear they may be essentially locked out of power in key institutions in the near future.

So, although they continue to hold immense cultural power, many Democrats likely feel powerless in the face of Trump’s second term, especially when he has the support of the Congress and, often, the Supreme Court too.

If we treat our political divides like a normal fire, one that simply requires stamping out a perceived threat, we will continue to make missteps, convinced that we’re helping extinguish the danger when in fact we’re feeding it with more kindling.

To put out this fire, we must first understand how it spreads: in the warped stories we tell ourselves about our opponents. Humans are skilled storytellers. We’re good at taking new tidbits of information and fitting them into our existing narratives. In the age of the internet, it is easier than ever before to use these bits to construct and bolster our preferred narratives. Decent people build stories from certain facts, emotions, and social worlds that make sense to them, but many come to view those who have different stories with contempt, accelerating the fire.

This is how we become arrogant, how we so easily fall for the “it’s obviously all their fault” framings that keep us mired in toxicity and contempt. Everyone believes they are on the side of good, but it’s often harder to see that in our ideological adversaries. Only when we understand them as people who also believe their views to be good and righteous, the same as ourselves, will we be better positioned to work towards our goals without dehumanizing, to work to persuade instead of provoke, and to stop feeding the blaze the vast majority of us wish to contain.

Zachary Elwood is the host of the psychology podcast People Who Read People and the author of How Contempt Destroys Democracy, in which he aims to persuade liberal and anti-Trump Americans of the need to work on reducing toxic polarization.

The biggest objection I hear to depolarization efforts is that people think it means embracing what they see as a false equivalency—a stance that “both sides are equally bad.” But it’s possible to reject the idea that both sides have contributed equally while acknowledging that both Democrats and Republicans have, in fact, played some role in perpetuating our current conflict.

A general response that might apply to a wide range of criticisms/response to this piece: When talking about these topics, I often get people responding to me who want to debate “who’s actually right” or “who’s actually more at fault” or "what group is actually worse." In my work, I make no claims about that (as I don’t think it’s productive; and it’s just not relevant to conflict resolution type work). What IS important to me is seeing how easy it is for rational, compassionate people to reach different conclusions about such matters, which I think is just very clearly the case. And I think it's important to see how reaching for team-based, us-vs-them approaches and contempt and anger (searching for definitive proof that "it's all their fault" or "see, they are worse, this proves it"), only ends up amplifying toxicity — and even ends up contributing to the very things about which we’re so angry/contemptuous.

We'll all believe what we believe about who's more at fault (that is natural and fine) -- but I think it's clear that you can continue thinking "one side is worse" (if that's what you believe) while also believing that it's extremely important to reduce toxicity and contempt and team-based thinking, because it's a self-reinforcing cycle.

This is a little dishonest, because all of the assassins of the past year have supported Left Wing causes, like "Free Palestine" or trans rights:

Elias Rodriguez 2 victims "Free Palestine"

Luigi Mangione 1 victim "Socialized Medicine"

Robin Westman 2 children LGBT rights

Mohamed Sabry Soliman 1 elderly woman, 6 others injured by firebomb "Free Palestine"

Loay Alnaji 1 elderly man killed "Free Palestine"

Tyler Robinson LGBT rights

Thomas Matthew Crooks, Trump shooter Anti-Trump

The man who firebombed Josh Shapiros house was also a "Free Palestine" nutjob.

I'm sorry but the majority of political violence these past two years are coming from one side. And it's not the Right.