With the 2024 presidential election increasingly in the rearview mirror and the 2026 midterms still more than a year away, political observers right now have their sights set on a handful of odd-year elections. One of the more high-profile contests that has received extensive media attention is New York City’s mayoral race, where self-identified socialist Zohran Mamdani looks on track to become the city’s next executive.

But most of us are typically looking elsewhere to gauge voters’ temperature roughly a year into a new president’s term: the races for New Jersey and Virginia governor, set to take place on November 4. TLP plans to provide our readers with in-depth analysis of these races in the coming weeks to help them better understand what to watch for in each one and what we the data might tell us about which party has the upper hand in them.

Next week, we’ll look at the present picture, including horse-race polling, the biggest issues in each race, and impact of President Trump. One week out from Election Day, we will unpack why Democrats appear to be (slight) favorites in both races, and how Republicans could also surprise. But today, we’re examining some historical trends to lay a baseline for how these states typically perform in off-year elections—and what that can tell us about the present.

1. The party that doesn’t control the presidency almost always wins the subsequent race for governor.

Just like in midterm elections, the president’s party typically pays a penalty in odd-year contests. A year into most presidential administrations, the public has often soured on the incumbent relative to their previous winning performance, and the result is an electorate that swings in the other direction.

This has been especially true in Virginia. The state’s transition from reliably red to quite blue has clearly changed its federal voting trends: Republicans have not carried Virginia’s electoral voters since 2004 or won a race for U.S. Senate since 2002. But contests for statewide, state-level offices—governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general, specifically—continue to be competitive and often susceptible to national political trends.

In fact, since at least 1980, Virginia has voted for the gubernatorial candidate from the party opposite of the president virtually every time. Only in 2013 did they buck this trend, backing Democrat Terry McAuliffe just after Barack Obama won a second term.

It’s not just Virginia, though. New Jersey, which has a much longer history than Virginia of voting blue at the federal level, has followed the same gubernatorial trend for nearly four decades. From 1989 to 2017, the party that did not control the White House won the governorship every time. In 2021, incumbent Democrat Phil Murphy bucked this trend for the first time in more than 30 years, retaining his seat in a nailbiter one year after Joe Biden captured the presidency.1

So, the governor contests in both New Jersey and Virginia usually—though don’t always—go the way of the “out-party.” If that trend persists this year, it would be good news for the Democrats.

2. A surge of white, working-class voters likely shifted the terrain in favor of Republicans in 2021.

In both states, Republicans had a notable turnout advantage last time around. In Virginia, for example, average turnout versus 2017 was up 132 percent in Trump counties compared to 117 percent in Biden counties. Moreover, while the average turnout increase in each of the state’s major metropolitan areas was roughly the same against 2017 (between 118 and 121 percent), it was up 136 percent across the rest of the state.

Most of the state outside its three major population centers—Northern Virginia, Richmond, and the Tidewater region—is disproportionately home to white voters without a college degree. Exit polls indicate that these voters broke for Republican Glenn Youngkin over Democrat Terry McAuliffe by a massive 52-point margin (76–24 percent), more than double the 24-point margin by which Trump won them over Biden there (62–38 percent). The shift was driven by white non-college women, who backed Youngkin by 50 points (75–25 percent) compared to Trump’s 12-point margin in 2020 (56–44 percent). On the whole, white non-college voters made up 36 percent of the electorate, up two points from 2020 and 10 points from 2017.

Though New Jersey did not conduct exit polls in 2021, it experienced similar county-level trends. In South Jersey, home to a higher concentration of white, working-class voters than the rest of the state, Democrats lost significant ground from 2020. Three counties they had won in the 2016 presidential election, 2017 gubernatorial election, and 2020 presidential election—Atlantic, Cumberland, and Gloucester—all flipped to the Republican candidate, Ciattarelli. What’s more: though all three were decided by fewer than seven points in 2020, Ciattarelli won them by double digits, outpacing Trump in every one.

It remains to be seen whether these Republican-leaning voters will turn out at the same rate now that their party controls the White House. But all this encapsulates a long-running issue for Democrats: their waning support among working-class and rural voters risks putting what were thought to be decidedly blue states back in play.

3. Both states shifted rightward from 2020 to 2024—a sign that they may not be as blue as once thought.

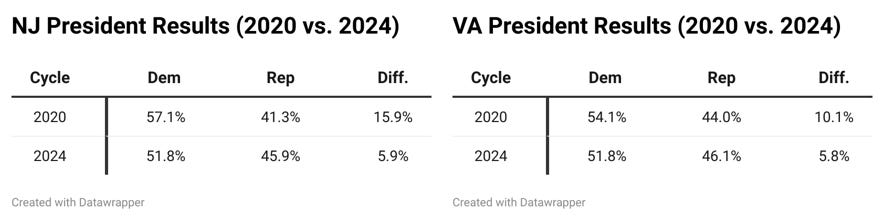

Another ominous sign for the Democratic Party is that both New Jersey and Virginia swung toward Trump last year. In the latter, he trailed Kamala Harris by fewer than six points (5.8 points) after Biden carried it by 10.1 points four years earlier. Even more surprising was that Trump significantly narrowed Democrats’ margin in New Jersey: while Biden won it by nearly 16 points in 2020, Harris carried it by less than half that and nearly the same margin by which she won New Jersey (5.9 points).

According to the AP VoteCast survey, key populations also shifted rightward during this period to an even greater degree than the statewide shift:

Of course, these surveys gauge partisan support among presidential electorates, so their utility in understanding this year’s electorate is limited. Still, they suggest that even though both states have been reliably blue at the federal level for at least a decade, Democrats can’t take these states or the voters in them for granted.

History offers a complicated picture of what we might expect heading into this year’s New Jersey and Virginia elections. Though the out-party penalty has had a real effect on odd-year gubernatorial results for decades, there are more recent signs that that Republicans in these two states are gaining ground and could punch above their weight. Next week, we’ll take a look at what the data show about the current contests in both states—and whether it clarifies anything.

Notably, Murphy fended off Republican challenger Jack Ciattarelli—the GOP’s 2025 nominee—who still overperformed his pre-election polling.

You left out two key issues roiling the Virginia race.

Virginia, which has much of the DC suburbs, has an exceptionally high population of federal employees and federal contractors, and a goodly number of recipients of various federal grants. Layoffs, shutdowns, and the revocation of grants and funding are thus a high tier issue. This was expected to help the Democratic slate, and appears to have been doing so.

Virginia has also had a scandal around the Democratic candidate for AG, Jay Jones, which Republicans are publicizing for all 3 major races. Advertising around this has been heavy on local news. The gubernatorial debate talked about Jones quite a lot, including in responses to unrelated questions. This appears to be hurting Jones, with some collateral damage to Spanberger and Hashmi.

So you have two countervailing wild cards swirling in the mix.

AG debate is Thursday (available online) and should be interesting.

My predictions, which in the last (un-fraud) presidential cycles have been perfect:

NJ right now is too close to call, but an R victory will not be a surprise at all. NJ has moved another 40,00+ to Rs since November, but Ds still have a big, big advantage and voter registration means almost everything.

VA goes D. Sears-Earle made a career mistake in attacking Trump last year. She has tried to walk it back, unsuccessfully. The R wins the AG race. VA does not report voter reg by party. I assume it is following NC and NJ trends, but again, voter registration means a lot and the gap was more than 5 points in each. By 2028 this will be a much different story: depopulating DC's liberals through reductions; deportations, continued D-R shifts will all make both states a true tossup in 2028. For now, VA is a bridge too far.