Over the past few weeks, two topics have been top of mind for many political and election observers: the continued poor standing of the Democratic Party (captured in several recent polls, which my colleague John Halpin covered well last week) and newly energized Republican efforts (and Democratic counter-efforts) to change congressional district maps mid-decade for a political edge in next year’s midterms. Both developments have prompted another question among many of these same observers: are the Democrats at risk of blowing it in next year’s midterm election?

With still over a year to go, it’s difficult to say with much confidence how things will shake out; after all, even a week can feel like a lifetime in the Trump era, let alone a full year. Still, more than six months into Trump’s second term, we’re getting a clearer picture of how his agenda is panning out, how the public is responding to it, and what this all might mean for the Democrats’ midterm hopes. Below are several factors we’ll be monitoring to gauge whether the party should anticipate a wave election next year—or a ripple.

Historical Trends

The primary reason Democrats are favored to make gains next November is that they are the “out” party, and out parties historically gain ground in midterm elections. Since the Civil War era, the president’s party has only gained House seats four times: 19021, 1934 (when FDR was building his New Deal coalition), 1998 (when Americans penalized Republicans for overreaching on Bill Clinton’s impeachment), and 2002 (when the country rallied around George W. Bush following the 9/11 attacks). Even in the last midterm election, which many analysts viewed as a win for President Biden’s Democrats relative to expectations, they still lost nine House seats and their majority.

In other words, it’s very likely that Democrats, who need to net just three House seats for a majority, will flip the House back. The Senate is more fickle, but the out party is likelier than not to make gains there as well. Over the same period, the president’s party lost seats in 24 of 42 midterm elections (or 57 percent of the time), and since the Depression Era, they have lost seats in 15 of 23 elections (or nearly two-thirds of the time). In a vacuum, Democrats should be favored to do well in the Senate, too.

House and Senate Maps

However, the maps for both chambers may present challenges to the Democrats as they work to win them back. Let’s start with the Senate, where Republicans hold a 53–47 majority. As their base has become more rural and working-class, the GOP’s structural advantage in Senate elections has deepened. This has made it more difficult for Democrats to regularly compete in many states.

This cycle’s Senate map is unlikely to help them, either. At first glance, the map should present them ample opportunities, as they are defending 13 seats to Republicans’ 22. But the nature of the seats on the ballot paints a rockier picture: the Cook Political Report rates fully 17 of those GOP-held seats safe and another three reaches for Democrats at best. Just two Republican seats are currently expected to be truly competitive: North Carolina and Maine. Meanwhile, Democrats must successfully defend four competitive seats of their own to have any chance of winning a majority.

Democrats may have a decent chance of defending all of their seats and snagging Maine and North Carolina, where they’ve struggled to win these Senate seats of late in part because they targeted them in unfavorable national environments such as 2014 and 2020.2 In a midterm year with a fairly unpopular incumbent president, they might be able to oust Maine’s Susan Collins, whose popularity has waned as of late, and finally win in North Carolina, which will have an open seat next year. However, Democrats still need two more Senate seats for a majority, which would have to come from states Trump carried by at least 11 points like Iowa, Ohio, and Texas.

In the House, the playing field is also quite narrow—and may become even more so by next November. Following the 2024 presidential election, Republicans kept their House majority. And while they experienced a net loss of one seat, leaving them with one of the narrowest majorities in history (220–215), the number of obvious future pick-up opportunities for Democrats coming out of that election was fairly low.

Part of the reason for this is that Democrats are starting from a higher floor this time around (215 seats) than they did in 2018 (194 seats). Moreover, the remaining seats on the board simply present fewer opportunities to go on the offensive. There are just three districts where both a Republican House candidate and Kamala Harris won last year, and at present the party is only favored to win back one of them (NE-02). Beyond those three, Cook considers just seven other Republican-controlled seats “toss-ups” and nine more “lean Republican.”

On the flip side, Democrats must defend at least ten “toss-up” districts of their own as well as 12 “lean Democratic” seats. This may not sound too hard: given that historical trends favor the out party and Democrats only need to net three seats for a majority, some might consider a Democratic majority a foregone conclusion. And indeed, they will be heavily favored to secure it.

However, Republicans aren’t going down without a fight. Under the direction of Trump, several GOP-controlled legislatures appear keen on redrawing their congressional maps to make Democrats’ task even harder. While Democrats hope to limit the damage through redraws of their own, their options for doing so are more limited. Thus, assuming they manage to flip the House anyway, they might need an even bigger national House popular vote (NHPV) margin if they hope to net more than a few seats and give themselves some breathing room on key votes.

Generic Ballot

One way to project which party is favored to win the House and what their final NHPV margin might be is through something called the generic ballot test (GBT). In surveys, pollsters will ask whether respondents favor the Republican candidate or Democratic candidate for their district’s House race. This measure offers a look at which way the race for the House majority might break.

Since 2004, pollsters have significantly reduced the GBT’s margin error, and it has correctly predicted which party would win the NHPV in every midterm election. Though the accuracy of the GBT hinges on its final, pre-election output, polling analysts have found that the survey question is often quite predictive even as far out as right now. According to CNN analyst Harry Enten:

[T]he generic ballot, even this early in a midterm cycle, can be quite predictive of the outcome of the following year’s House elections. Once you control for which party is in the White House, the generic ballot about 18 months before a midterm election is strongly correlated (+.78) with the eventual House result—i.e., the share of votes cast for the president’s party versus the share of votes cast for the opposition party.

If this trend holds, it may not be welcome news for Democrats. As of this week, the party held a 2.9-point average lead in the GBT. Though a nearly three-point lead might sound meaningful, consider that at the same point in the 2018 cycle—where they went on to flip 42 Republican House seats—Democrats enjoyed around a seven-point advantage, which grew to over ten points by November 2017. One year later, they won the NHPV by 8.6 points, the largest margin in a midterm election in more than 30 years.

There is of course still time for Democrats to improve their advantage here. But it is concerning that they have been unable to grow their GBT advantage even as Trump’s approval has declined, especially when support from self-identified Democrats in those polls is near-unanimous. This means they’ll likely need to gain substantial ground with independents to boost their midterm hopes.

Democratic Favorability

One major difference between this cycle and 2018 is that Democrats are far less popular this time around. Recent surveys have shown the party’s standing hitting historic lows while Republican self-identification among the public hit its highest point in more than 30 years in January. Democrats’ longstanding edge in voters registration has also seen a steady decline since that midterm election.

Despite all this, Democrats could still have a good midterm, and they don’t need to look very far back to find a historical parallel for their situation. Heading into the 2008 presidential election, Republicans were saddled with an deeply unpopular incumbent president, his deeply unpopular foreign war, and a deeply unpopular bailout of Wall Street, whose actions had brought the global economy to the brink of a depression.

In the face of this, Barack Obama won a decisive victory and entered his first term with historically large majorities in Congress. At the start of the new Congress, Republicans’ approval rating was a paltry 28 percent, and they were down big with even their own voters. Things looked bleak. Then, the following November, they made historic gains of their own, capturing the greatest number of House seats (64) in a single election since the Great Depression.

As RealClearPolitics’ Sean Trende has observed, one of the reasons so many people in 2010 didn’t buy the “red wave” narrative was that Democrats maintained a higher favorability in pre-election polling than Republicans. Today, it’s Republicans who enjoy a slightly higher favorability. None of this assures that Democrats will bounce back with a historic win like Republicans did 15 years ago, but it’s enough to caution against linking Democrats’ current polling woes to their midterm prospects. Much of their lackluster polling stems from dissatisfaction among their own voters, who likely want to see them fight Trump more than they are. It’s a good bet many of them will come home by next November.

Presidential Approval

Another strong historical predictor of midterm results is the approval rating of the incumbent president, which correlates highly with their party’s seat loss in the House. The only presidents in the polling era whose parties experienced a net seat gain in a midterm election (Bill Clinton and George W. Bush) enjoyed approval ratings north of 60 percent (66 percent and 63 percent, respectively). But even a strong approval rating doesn’t guarantee success for a president’s party.

For example, in 1958, President Eisenhower’s approval rating ahead of the midterm was a very respectable 57 percent, but the Republicans experienced a net loss of 48 House seats. More recently, George H.W. Bush’s 58 percent helped blunt deep losses in 1990, but Democrats still flipped eight seats.

But Obama’s two midterm elections offer even more relevant parallels. Ahead of each one, his approval rating sat at 44 to 45 percent, mirroring Trump’s approval today. The result was two abysmal showings in which Democrats collectively lost 77 House seats and were set back nationally at least a generation.

In his first term, Trump’s Republicans lost 42 House seats. Given the more constricted House map this time around, it’s very unlikely his party’s losses will be that deep next year, no matter his personal standing. However, a low approval won’t do them any favors, and what it looks like by next November is contingent on what’s going on elsewhere by that time.

State of the Economy

One factor that often sinks the fortunes of any president is a sour economy. Look no further than last year’s election. Four-in-ten voters said the top issue facing the country was the economy and jobs, and they broke for Trump over Harris by 61 to 37. Swing voters, specifically, identified inflation as a key reason why they chose not to vote for Harris.

To be sure, even a good economy may not prevent midterm losses for the president’s party, as Trump himself experienced in 2018. But a bad one often leads to electoral pain for the “in” party, as many swing voters will cast their ballot with the economy at the top of mind. Though Trump arguably won his second term primarily because voters trusted him over Harris to get the economy back on course, many view his early actions with great unease—and now attribute their frustrations to his policies.

A recent Morning Consult poll found that six-in-ten Americans blame Trump’s policies for driving up the cost of living, while just one-in-four said in a recent AP-NORC poll that they believe his policies have helped them. Trump’s approval on the economy has been underwater since mid-February and currently sits at around -12 percent. It is even lower for his handling of trade (-17 percent) and inflation (-26 percent).

However, as 2022 showed, voter frustration over the economy—and inflation, specifically—isn’t guaranteed to wreck the fortunes of the incumbent president’s party. That year, a majority (51 percent) of voters said that inflation was “the single most important factor to their vote,” and fully one-third still voted Democratic in their House contest. In fact, though inflation stood at 7.8 percent ahead of the midterm election, Democrats managed to avoid sweeping defeats across high-profile battleground races. Further complicating the picture is research from the American Presidency Project, which finds a weak historical relationship between inflation and midterm seat gains or losses.

So, while a fragile economy is never an asset for an incumbent president or their party, it may not necessarily spell doom for them either.

The Turnout Factor

Another reason why Democrats are thought to have an advantage heading into next year is that their new coalition includes many reliable voters. In 2022, when history says they should have suffered a crushing midterm defeat, Democrats prevailed in key races thanks to higher turnout among crucial constituencies. Similarly, they have been overperforming in special elections every cycle since Trump first took office. Some analysts have attributed this to the party’s new, highly engaged coalition.

Trump’s return to power and early controversial moves have strengthened the resolve of many core Democratic voters, who are strongly motivated to turn out next year. A CNN poll from last month found that even as the party’s image was in the dumps, their voters were fired up:

Overall, 72 percent of Democrats and Democratic-aligned registered voters say they are extremely motivated to vote in next year’s congressional election…That outpaces by 10 points deep motivation among the same group just weeks before the 2024 presidential election and stands 22 points above the share of Republican and Republican-leaning voters who feel the same way now.

However, Democrats should not expect that Republicans won’t be highly motivated by next fall as well. David Wasserman notes that while Democrats had a turnout edge in special elections in 2017 and 2018, their sizable advantage diminished in the midterms “because both parties’ intensity levels surged in a more nationalized context.” Democrats’ edge over Republicans was still “good enough to capture 235 House seats—just not the 270 seats they would have captured had November followed the 63 percent vs. 48 percent turnout pattern of the specials.”

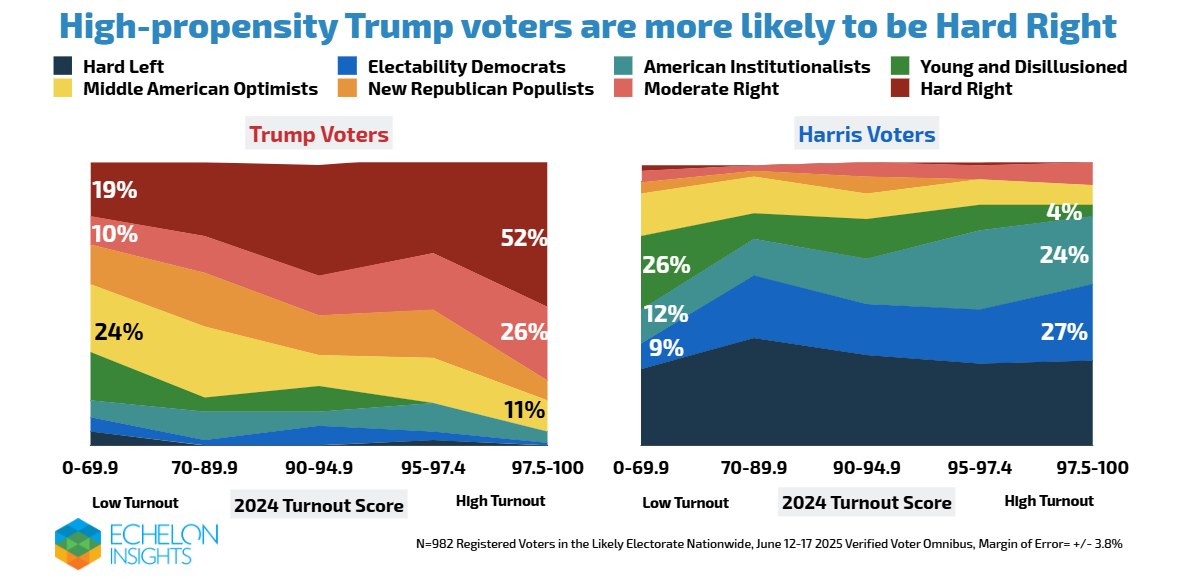

Things have also changed since then. In just the last midterm election, loyal MAGA voters were among the highest-propensity voters. According to a recent study by the polling firm Echelon Insights, among all Trump voters, the “Hard Right” constituted an outright majority (52 percent) of those who were likeliest to vote—twice the size of the next group and far larger than any group of Harris voters.

Democrats will still likely hold a turnout advantage in next year’s midterm, but they shouldn’t be surprised to see a Republican surge around Election Day that could blunt significant gains.

Issue Salience

Finally, the issue landscape may be giving Democrats a break. An April Gallup poll found that the top issues Americans worried most about all concerned their wallets: the economy generally (60 percent worried “a great deal”), healthcare access and costs (59 percent), inflation (56 percent), federal spending and the budget deficit (53 percent), and Social Security (50 percent). Meanwhile, immigration, by far the Democrats’ worst issue, has been declining in salience, and other recent Gallup polling has shown that Americans’ concerns about immigration levels have also decreased since last year.

Democrats would surely rather talk about Trump’s handling of the economy, for which he is receiving dreary marks from the public, than immigration. If the economy continues to face challenges ahead of next year’s midterms, it may offer the party a strong issue on which to run in swing states and districts.

Though we at TLP often write about the need for Democrats to develop an alternate vision to Trump to sell to voters, the reality is also that midterm elections are usually a referendum on the incumbent president (and their party). So the fact that Democrats are still struggling to coalesce around a shared vision for the future doesn’t necessarily signal anything about how they will perform next year. But even as we acknowledge they should do well in the midterms, there is also evidence that the road ahead may not be without its challenges.

According to the Brookings Institution, “Although the Republicans [who controlled the White House] gained nine seats in the 1902 elections, they actually lost ground to the Democrats, who gained twenty-five seats after the increase in the overall number of Representatives after the 1900 census.”

Yes, Democrats won the presidency in 2020, but they lost seats in the House and likely only captured the Senate thanks to winning two of their seats in lower-turnout runoff elections.

You forget the other important advantage the Democrats have - the 100% tongue bath the media will give their candidates.

Dems may win the battle, to lose the war. One would assume the inclination to impeach Trump yet again, if Dems take the House, will be strong. A conviction, which requires 2/3rds of the Senate is a mathematical impossibility.

Dems would successfully eat up much of Trump's final 2 years in office, but US voters appear to have lost patience with Democratic constant legal attacks. It is how Trump morphed a mug shot into a second presidential portrait.

Contingent on the economy and border, combine an impeachment that will surely fail, with NYC honest to God socialist/communist Mayor for 3 years, and 2028 may look OK for Reps, even if they lose the House in 2026.