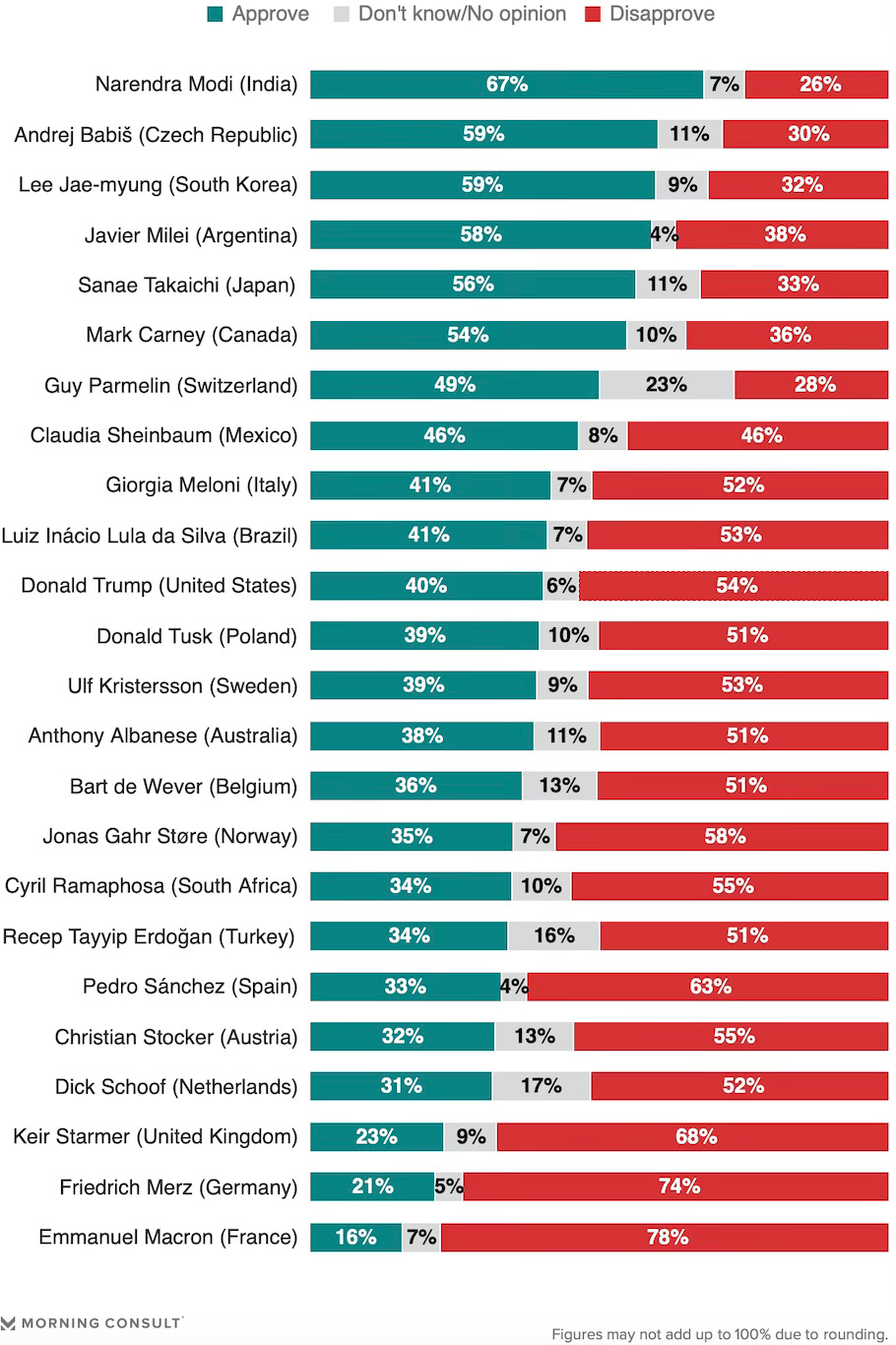

Among leading democracies, there are only seven world leaders today with net positive job approval ratings, according to Morning Consult’s latest tracker: Narendra Modi of India (+41 percent), Andrej Babiš of the Czech Republic (+29 percent), Lee Jae-myung of South Korea (+27 percent), Javier Milei of Argentina (+20 percent), Sanae Takaichi of Japan (+23 percent), Mark Carney of Canada (+18 percent), and Guy Parmelin of Switzerland (+21 percent).

That’s it. Call these countries the new P-7, those with leaders who enjoy popular support from most of their voters.

In contrast, 16 other leaders included in the study all receive net negative job approval from their citizens, ranging from –11 percent to –62 percent, with Keir Starmer of the UK, Friedrich Merz of Germany, and Emmanuel Macron of France bringing up the rear of the pack. Mexicans are split on Claudia Sheinbaum, while President Trump lands in the middle of the table at -14 percent net job approval, clustered around Italy’s Giorgia Meloni (-11 percent), Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (-12 percent), and Poland’s Donald Tusk (-12 percent).

Popularity is not an exact science, but if you look at the new P-7’s most successful leaders, they seem to be of two types: (1) strong or pragmatic heads of state like Lee, Takaichi, Carney, and Parmelin, or (2) populist-nationalist outsiders like Modi, Babiš, and Milei. This is not a left-right dimension. Takaichi is a social conservative who just won a resounding election victory with tough stands on immigration and defending Japanese interests against China, and Carney is a social liberal who has forcefully pushed back against Trump’s various attacks on his country and others. Modi is a religious nationalist, and Milei is a libertarian populist. Lee, Parmelin, and Babiš are viewed as steady hands or common-sense reformers. Most importantly, all seven of these leaders match the national mood in their respective countries, Modi perhaps most of all.

In contrast, the world’s more unpopular leaders all suffer from similar problems that do not match the prevailing sentiments of their national populations.

Interestingly, this is not an ideological development. Conservative leaders like Trump and Merz, center-left leaders like Starmer and Pedro Sánchez of Spain, and centrist ones like Macron and Jonas Gahr Støre of Norway are all suffering poor job approval. Likewise, high or low ratings for national leaders do not correspond precisely with more objective economic conditions in respective countries. For example, Mark Carney is doing very well in Canada with a less than one percent projected GDP increase for 2026, according to The Economist, as is Narendra Modi in India with a smashing 6.2 percent projected growth increase for the year. Argentina still faces many economic challenges, including a projected 19 percent inflation rate for this year; however, Javier Milei is performing quite well with voters. Meanwhile, in the United States, overall growth remains positive, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average just crossed a record-high 50,000-point threshold, yet Trump is struggling with American voters.

A few themes do emerge to help explain why so many leaders are unpopular. One, they are polarizing figures who split electorates. Trump and Turkey’s Erdoğan most come to mind here; their supporters really like them, and their opponents fervently despise them. Two, they are viewed by voters as either corrupt (like South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa) or as out-of-touch elites failing to bring about changes that many voters demanded (like Macron or Starmer). Three, they are not addressing voters’ long-standing economic concerns that have been mounting for decades. Although overall economic measurements do not match exactly with job approval ratings, some of the worst-performing leaders in this research are overseeing years of seemingly stagnant national growth—for example, the UK, Germany, and France are all projected to see meager one percent increases in growth this year, and their respective leaders are at the bottom of the heap in terms of job approval.

There is no grand theory of world leader success. But the winners of the popularity contest highlighted here do show that the right combination of appealing personal traits, competence in government, and a commitment to protecting national interests internally or against external threats can convince voters that a leader is doing a good job. Alternatively, an unappealing personality, overall incompetence or aloofness, and efforts to undermine internal cohesion or national interests will get you serious demerits from voters.

I often read economists trying to tell me how great things are based on GDP, wages, soy exports, etc, what they all seem to miss is that all that crap has nothing to do with how most of us live our lives.

Governments are supposed to keep us safe, enforce the law, and take care of all those things that businesses aren't real good at doing, and around the world, governments are on vacation or something.

In the US there is this feeling like the whole thing isn't working out for most people, and there's nothing we can do about it because whoever we elect is just corrupted by the system anyway.

We have no party for the bottom four income quintiles.

Interesting observations. Just remember that all politics is local. Factors in one country do not always transfer or apply to others. The only "constant" has been the rise of anti-elite populism in countries smothered by bureaucracies and administrators, including the United States. In that sense, Canada is a huge exception.