Editor’s note: We covered this topic before the election as it related to Kamala Harris’s campaign for president. Recent events have put the question back in the public spotlight, so we wanted to address it again. The following includes some points from our pre-election piece.

Former First Lady Michelle Obama made headlines recently when she remarked that the U.S. is “not ready for a woman” president, a not-so-subtle scolding of the American public. Commenting on the 2024 presidential election, she added that the country has “a lot of growing up to do… As we saw in this past election, sadly, we ain’t ready.” This week, longtime Democratic leader Jim Clyburn said that Mrs. Obama was “absolutely correct” in her critique.

This is far from the first time that the U.S. has faced criticism for having failed to elect a female executive in its nearly 250-year existence, especially given that many other western democracies around the world have already done so. And this drought—including America’s failed attempts to break the barrier in 2016 and 2024—has given rise to an enticing narrative for some: that the country is years, perhaps generations, away from seeing a woman reach the pinnacle of American political power.

It is sadly true that women are still often held to a different standard than men in politics. However, that does not therefore mean that they cannot win, even at the highest level. And perpetuating such a grim reading of American society and election history is not just misguided; it risks dissuading talented women from considering running for public office in the future.

The Clinton and Harris Case Studies

One of the most common data points cited as evidence that America has a sexism problem in politics is the defeats of Hillary Clinton and Kamala Harris—and at the hands of Donald Trump, whose history of derogatory remarks toward women (including both Clinton and Harris) was widely documented ahead of those elections. It’s an appealing explanation, as it seems the most straightforward: America has twice had a chance to elect a woman as president, and both times it declined. Therefore, sexism is preventing women from reaching the Oval Office.

However, this theory, based on a sample size of two, oversimplifies some things. First, it ignores an important fact: Clinton won a majority of all votes cast in 2016, and her national lead over Trump in the popular vote—nearly three million (or 2.1 points)—wasn’t particularly small. In most western democracies, that would have made her the winner1. Moreover, Trump’s national vote share was just 45.9 percent, the lowest for a winning Republican nominee since 1968 and even lower than Mitt Romney’s 47.1 percent in 2012. Clinton’s 48 percent support was on par with other recent Democratic nominees who lost, including John Kerry (48.3 percent) and Al Gore (48.4 percent), the latter of whom also famously won the popular vote. Ultimately, Trump became president thanks to 77,744 votes across three Midwestern states that gave him an Electoral College victory—hardly a total repudiation of Clinton.

Additionally, Trump did not improve on Mitt Romney’s 2012 performance with men. Both won 52 percent, barely a majority.2 Also instructive: Trump essentially matched Romney’s support among self-identified Republicans, with both winning roughly 90 percent. This doesn’t exactly suggest that Trump’s Electoral College advantage over Romney was powered by misogyny; on the contrary, much of his backing simply came from voters who traditionally leaned more Republican than Democratic and who were thus likelier to support Trump’s policies over Clinton’s.

Democrats did, however, have a problem with men in 2024, when Trump won the largest share of the male vote (56 percent) of any of his three elections. But as we have documented previously, the party’s problems were more multifaceted than sexism could account for—and they were not exclusive to Harris. According to post-election data from the Democratic firm Catalist, Trump won 57 percent of men while Harris won 41, a picture that was virtually identical in the House, where Republican candidates won 57 percent of men compared to Democrats’ 42 percent. Or consider Pennsylvania, arguably the most important swing state in the election. Harris lost men there to Trump by a margin of 44 to 55. In the state’s Senate race, Democratic incumbent Bob Casey lost men to his Republican challenger, 44 to 54.

Another issue with the sexism explanation is that it reduces the results of years-long campaigning to a univariate cause. Let’s start with 2016. It’s exceedingly rare for a political party to win the three consecutive presidential terms. Since the adoption of the 22nd amendment in 1951, it has only happened once: when George H.W. Bush succeeded Ronald Reagan. History was thus not on Clinton’s side. She also famously never visited the key swing state of Wisconsin, which broke for Trump by just 0.7 points (or 22,748 votes) and which she would have won if she’d merely matched Obama’s vote total in deep-blue Milwaukee from 2012.

Additionally, both Clinton and Trump were historically unpopular. While Clinton’s high unfavorables may have been in part due to sexism, they also likely reflected her association with an elite political class that many Americans had grown weary of since the Great Recession, a perception that her deep ties to Wall Street—a recurring campaign issue—surely didn’t help. This became a clear liability as the U.S., like several other Western countries, was beginning to take a populist turn.3

Similarly there were myriad factors behind Harris’s loss last year, which TLP has written about extensively. Among some of the most notable factors: President Biden’s abysmal approval rating, Harris’s association with the Biden administration (and subsequent refusal to distance herself from it), global post-pandemic outrage over inflation and mass migration, Harris’s well-documented past unpopular positions (many of which she also hesitated to fully rebuke), and the erosion of the party’s support among the working class. In other words, Harris, like Clinton, represented an establishment that a lot of voters, including some who had long comprised the Democratic base, were fed up with.

Moreover, as women—specifically, college-educated women—make up a growing share of the Democratic base, many (often younger) men have grown skeptical that the party is looking out for their interests as well. Harris made strong appeals to women during the campaign but never seemed to do the same for men. But post-election analysis by TLP and others has made clear that it was a combination of all these factors that helped lead to her defeat.

As these two case studies demonstrate, a key shortcoming of the sexism narrative is that it (dis)misses other, more holistic explanations for Clintons’ and Harris’s losses. The U.S. also finds itself today in a highly polarized political environment4. A growing number of Americans simply vote straight-ticket and are unwilling to support candidates of the other party—no matter their race or gender. And the intensifying populist fervor infecting American politics over at least the last decade has produced constant backlash against whichever party is in power.

Even amidst all this, women have still found much success. For example, while Harris lost, scores of female candidates won races for statewide and federal office in 2024, including several in places where Trump also won. To date, just eight states have never elected a female governor or U.S. senator, and all 50 states have at some point elected a woman at the statewide level. That doesn’t mean men and women are at parity, but it paints a more promising picture than the cynics portray.

What the Research Shows

There is also a growing body of academic research suggesting that the sexism theory isn’t as strong as some believe. For starters, attitudes about gender are now largely baked into voters’ partisan loyalties. Political scientists Brian Schaffner and Danny Hayes analyzed survey data and found that “sexist voters opposed Clinton in 2016 – but not necessarily because she was a woman.” They added:

Notably, people who agreed with sexist statements in the survey also rated Obama and Clinton unfavorably at nearly identical rates. To the extent that Obama was more popular than Clinton, it was actually among voters who rejected sexist statements. This is not what we would expect if sexist voters were penalizing Clinton, in particular.

And:

Biden and Harris’ favorability ratings were virtually identical for respondents at various levels of sexism. For instance, among respondents who expressed the strongest agreement with sexist statements, both Biden and Harris had favorability ratings of approximately 12 on a 100-point scale.

In other words, voters who hold sexist attitudes would already be highly unlikely to vote for Democrats for a host of reasons having nothing to do with gender. And insofar as those views exist in the electorate, they negatively impact all Democrats, not just women.

But here’s the thing: such attitudes are not necessarily that widespread to begin with. University of Oxford researcher Dr. Sanne van Oosten conducted a meta-analysis examining how race and gender impact candidates for office, mostly in the U.S. She found that “on average, voters do not discriminate against minoritized politicians.” In fact, she adds, “women and Asians have a significant advantage compared to male and white candidates.”

Journalist Zaid Jilani spoke to van Oosten about her findings:

Her conclusion from the studies…was optimistic. Voters don’t penalize female and minority candidates; in fact their first impressions are even more positive about female and candidates [of] some minority backgrounds.

“Voters aren’t negative—in some cases [they are] even positive about women, about Asian candidates, and think the same about black candidates as they do about white candidates. It’s actually quite positive,” she told me in an interview.

Despite this seemingly welcome news, many Americans—especially liberals—have become more pessimistic about racial and gender progress, and this can have real consequences. As van Oosten noted, when people misunderstand the state of the world around them, they often make ill-advised decisions. “Even though voters’ first impressions are not negative towards politicians of color or women,” she wrote, “party selectors might assume they are and might therefore fear selecting a woman of colour for an important role.”

CU-Boulder professor Regina Bateson similarly found that voters often overestimate the ubiquity of racism and sexism in American life, which can lead to misperceptions around what kind of candidates are “electable.” As she writes:

Why are women and people of color under-represented in U.S. politics? I offer a new explanation: strategic discrimination. Strategic discrimination occurs when an individual hesitates to support a candidate out of concern that others will object to the candidate’s identity.

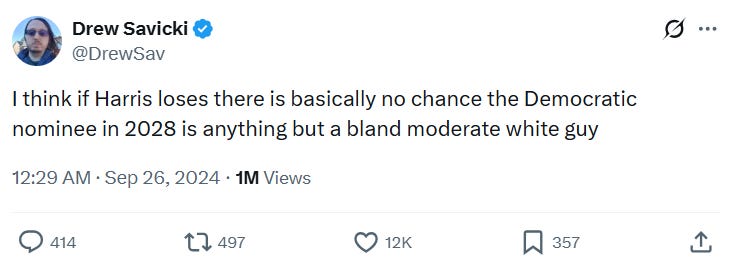

Ironically, this type of thinking might make it even harder for minorities and women to gain support when they could in fact win, as those who believe sexism is rampant may convince themselves that their party risks losing key races if they nominate a woman (or a minority candidate). This rather troubling view was perhaps best captured in a viral pre-election tweet:

Unfortunately, this sentiment is likely to prove correct. There are certainly plenty of prospective candidates who fit that profile and would be strong contenders for the party. But Democrats may assume the country won’t be open to voting for any other type of candidate, and that misperception could lead them to needlessly forgo talented options for president.

As humans, we often subscribe to certain narratives about the world that jibe with our pre-existing understanding of it. The risk, of course, is that we develop blind spots that inhibit our ability to see things clearly. In this case, many Democrats have come to believe that sexism (and racism, too) are more widespread than they are, and that minority candidates are at a disadvantage because of it—despite ample evidence to the contrary. In addition to hurting their own candidates down the road, this risks reinforcing a deeply pessimistic perception that some on the left have of the U.S.

The good news is that identity does not play as large a role for many voters as some fear. Democrats would benefit from understanding this and readjusting how they think about wins and losses. The country already broke one major barrier in 2008 and again in 2012 because Democrats ran a candidate who spoke to voters’ anger at Washington and Wall Street. Many people ultimately voted for him despite his skin color.

The lesson in all this may simply be that Americans don’t care much about candidates’ identity traits one way or another. They just want politicians whom they believe share their values and are looking out for them—and who aren’t reflexive defenders of the establishment.

This is merely a statement of fact, not a provocation to debate the Electoral College versus the national popular vote.

Data showing how various demographic groups voted comes from averages across four datasets: the Edison exit poll, AP VoteCast survey, Catalist “What Happened” report, and Pew validated voter analysis.

And let us not forget the scandal regarding her private email servers, the WikiLeaks hack, her “basket of deplorables” comment, the infamous Comey letter…

Interestingly, this may actually help to crowd out sexist or racist attitudes in the minds of voters who hold them, as their views on other issues begin to take greater precedence.

Britain elected Thatcher who had essentially the same politics as Reagan. I suspect that if the genders were reversed they’d have still been elected. Italy elected Giorgio Merloni, a conservative.

I wouldn’t be surprised if conservative women had an advantage- a Queen Elizabeth like mama bear fighting for her people. But leftist women are at a disadvantage because they are weak where they should be strong. A male leftist is free to be an authoritarian ideologue in a way that female leftists cannot.

edit: I should square the circle - leftism is weak in that its the politics of decay and decline, not greatness. Hence the MAGA movement. But it’s also authoritarian, seen most clearly in Europe where people are arrested for social media posts and freedom of speech no longer exists.

Edit 2: “ Harris made strong appeals to women during the campaign but never seemed to do the same for men”

Have we forgotten White Dudes for Harris so quickly?

This is a red herring, akin to questioning whether Americans will ever elect a Black person, pre Obama. Americans would have elected Colin Powell long before Obama, by large margins, but he did not run. His wife wanted him home and she feared assassination.

Americans would have no problem electing a woman, just not the two options offered. Clinton, literally, labeled 1/2 the country racists, homophobes and xenophobes. After she lost the election, completely unprompted, an adult niece labeled Hilary the Aunt every niece or nephew in America will pay money to avoid at Thanksgiving.

Harris may be gone from DC, but her policies and their aftermath permeate Blue states. Toothpaste is locked up like nuclear material and homeless encampments cover sidewalks. Actual decriminalization of theft and de facto decriminalization of drugs were Kamala's CA mission priorities. After she completed them, the ideas spread, like a cancer. How about the billions spent on electric school buses never delivered after payment, or permanently mothballed in school garages because they will not run? Who can forget Kamala ending mass migration, by discovering the root causes?

Kamala was the Queen of horrendous policy, before people considered the fact it is difficult to run the Free World, when one lacks the ability to string together two coherent sentences. We will have a female President, when Americans are presented with a viable female candidate.